The Museum of London Archaeology’s excavation of the site of Bloomberg’s future European headquarters in central London has proven to be an even richer archaeological motherlode than we knew. Thanks to its proximity to the Thames and the waterlogged embrace of the lost Walbrook River, organic remains from the earliest days of Roman London through the 5th century were preserved in exceptional condition: entire streets, hundreds of shoes, a cavalry harness and the largest collection of fist and phallus amulets ever found. When the story broke in 2013, archaeologists had unearthed more than 100 fragments of writing tablets. That was just the beginning. In the final tally, a total of 405 wood writing tablets were found during the Bloomberg Place excavation. Only 19 tablets were discovered in London before this.

The Museum of London Archaeology’s excavation of the site of Bloomberg’s future European headquarters in central London has proven to be an even richer archaeological motherlode than we knew. Thanks to its proximity to the Thames and the waterlogged embrace of the lost Walbrook River, organic remains from the earliest days of Roman London through the 5th century were preserved in exceptional condition: entire streets, hundreds of shoes, a cavalry harness and the largest collection of fist and phallus amulets ever found. When the story broke in 2013, archaeologists had unearthed more than 100 fragments of writing tablets. That was just the beginning. In the final tally, a total of 405 wood writing tablets were found during the Bloomberg Place excavation. Only 19 tablets were discovered in London before this.

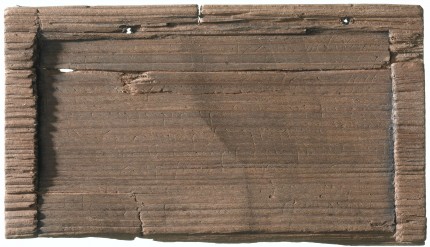

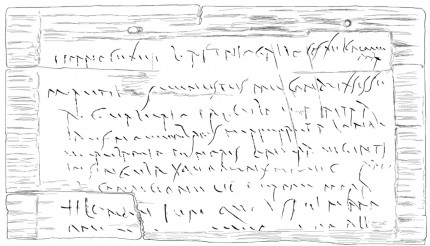

These wooden tablets were the notepads of the Roman world. Coated in a layer of blackened beeswax, the writing was scratched on the surface with a stylus, usually in cursive Latin. They were used for correspondence, contracts, financial records, school lessons, anything else that needed writing down. While the beeswax is long gone, the impression of the writing sometimes marked the wood making it possible to read the tablets. Possible, but far from easy. High resolution photography with raking light and microscopic analysis can reveal the faint markings. Even when visible, cursive

These wooden tablets were the notepads of the Roman world. Coated in a layer of blackened beeswax, the writing was scratched on the surface with a stylus, usually in cursive Latin. They were used for correspondence, contracts, financial records, school lessons, anything else that needed writing down. While the beeswax is long gone, the impression of the writing sometimes marked the wood making it possible to read the tablets. Possible, but far from easy. High resolution photography with raking light and microscopic analysis can reveal the faint markings. Even when visible, cursive Latin is no picnic to read. Cursive Latin expert Dr. Roger Tomlin was enlisted to crack the tablet code, which is very much how he sees the work.

Latin is no picnic to read. Cursive Latin expert Dr. Roger Tomlin was enlisted to crack the tablet code, which is very much how he sees the work.

“The Bloomberg writing tablets are very important for the early history of Roman Britain, and London in particular. I am so lucky to be the first to read them again, after more than nineteen centuries, and to imagine what these people were like, who founded the new city of London. What a privilege to eavesdrop on them: when I decipher their handwriting, I think of my own heroes, the wartime academics who worked at Bletchley Park.”

Out of the 405 tablets, 87 have been deciphered thus far, more than quadrupling the known letters from Roman London and shedding new light on the early decades of the city.

Out of the 405 tablets, 87 have been deciphered thus far, more than quadrupling the known letters from Roman London and shedding new light on the early decades of the city.

More than 1,300 wooden writing tablets have been unearthed at the fort of Vindolanda in Northumberland just south of Hadrian’s Wall, most of them letters to and from the soldiers stationed there, but the earliest date to 85 AD when the first timber fort was built. The earliest of the Bloomberg tablets to include a date is a financial transaction from January 8th, 57 A.D. It reads:

“In the consulship of Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus for the second time and of Lucius Calpurnius Piso, on the 6th day before the Ides of January. I, Tibullus the freedman of Venustus, have written and say that I owe Gratus the freedman of Spurius 105 denarii from the price of the merchandise which has been sold and delivered. This money I am due to repay him or the person whom the matter will concern…”

It’s the oldest intrinsically dated writing in Britain and the earliest legal document. It was written less than 14 years after the conquest and three years before the Boudiccan revolt.

Another tablet is even older although its author didn’t do us the favor of dating it for us. It was stratigraphically dated to 43-53 AD, the first decade after the Roman conquest of Britain. There’s also the first written reference to Roman London, a tablet from 65-80 AD addressed to Londinio Mogontio, meaning Mogontius in London. (Mogontio only pawn in game of life.) The next reference would come 50 years later in Tactitus’ Annals 14.33 where he describes the Boudiccan revolt.

Speaking of which, one of the tablets illuminates how quickly the city of London recovered from the devastation of the insurrection. It’s a contract dated October 21st, 62 A.D., a year after the revolt, which arranges for the transportation of “twenty loads of provisions” from Verulamium (modern-day St Albans, Hertfordshire) to London, a distance of about 25 miles, by November 13th.

Almost 100 proper names of individuals from various walks of life — emperors, soldiers, a brewer, a judge, a cooper, freedmen, slaves — have been identified in the tablets. The earliest residents of Roman London were primarily soldiers and businessmen, most of them originating from Gaul and the Rhineland. One significant name mentioned is that of Julius Classicus, a nobleman of the Belgic Treveri tribe, who would go on to become a leader of the Batavian revolt (69-70 A.D.) that broke out in the province of Germania Inferior after the assassination of the emperor Nero. A few years earlier, around 65 A.D., he was the prefect of the Sixth Cohort of Nervians, an auxiliary infantry cohort in London. One Julius Classicianus, in all likelihood a relative of Classicus’, was procurator of Britain from 61 to 65 A.D. so he probably pulled a few nepotism strings to give his kinsman the commission. Before this the earliest confirmed presence of the Sixth Nervians in Britain was 122 A.D. and they were known to have remained in the province until the end of the 4th century shortly before the Roman withdrawal in 410. Now we know they were there practically from the beginning too.

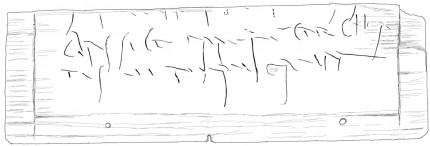

Another intriguing tablet doesn’t actually say anything. Dating to around 60-62 A.D., it’s just the last two lines of the alphabet, “ABCDIIFGHIKL / MNOPQRST.” A few letter are missing. This was probably writing practice, maybe even schoolwork. If it is, it would be the first evidence of Roman schooling discovered in Britain.

Another intriguing tablet doesn’t actually say anything. Dating to around 60-62 A.D., it’s just the last two lines of the alphabet, “ABCDIIFGHIKL / MNOPQRST.” A few letter are missing. This was probably writing practice, maybe even schoolwork. If it is, it would be the first evidence of Roman schooling discovered in Britain.

The tablets were cleaned and conserved using PEG, a waxy substance that replaces the water in saturated wood preventing it from drying and cracking. They were then freeze-dried for long-term conservation. The tablets will continue to be studied at MOLA. At least one of them, the earliest intrinsically dated tablet in Britain, will be part of the permanent public exhibition in the new Bloomberg building which will display more than 700 of the 10,000+ artifacts discovered in the excavation, plus the reconstructed London Mithraeum. It’s scheduled to open in fall of 2017.

The tablets were cleaned and conserved using PEG, a waxy substance that replaces the water in saturated wood preventing it from drying and cracking. They were then freeze-dried for long-term conservation. The tablets will continue to be studied at MOLA. At least one of them, the earliest intrinsically dated tablet in Britain, will be part of the permanent public exhibition in the new Bloomberg building which will display more than 700 of the 10,000+ artifacts discovered in the excavation, plus the reconstructed London Mithraeum. It’s scheduled to open in fall of 2017.

[youtube=https://youtu.be/lhm-n09PGEI&w=430]

Yes yes, all right .. BUT .. apart from sanitation, education, wine, irrigation, roads, the fresh-water system, and public health – What have the Romans ever done for us ?

OK, writing on tablets, the European union and now even financial bills of exchange .. But what have they done for us ? .. I would really like to know.

And once you put “paid” to the bill, you’ve got a perfect fire starter.

I repeat my generous offer: anyone who would like to come and dig our back-garden for us in hopes of finding Roman rubbish, oops Roman treasure, is welcome. Plan to spend as much of October as you like: the soil becomes pretty undigable after that until Spring.

These tablets sound like they could have been re-coated with wax and used again.

On top of everything else, imagine the nightmare of trying to read multiple sets of indentations in a single wood base!

Oh,wonderful! I loved Latin in jr high; it was my first window to a long-ago culture. Very good teacher who didn’t teach it as a “dead” language, as it lives on in many modern languages. What fascinated me most were the then not very visible glimpses into day-to-day life. These tablets are like opening another window. It is the first time I’ve seen “cursive” Latin– ay ay ay, I’m glad someone can read it!

How did I miss this discovery in 2013? How exciting and amazing to have documents from the first days of London. Thank you for your article and the photos! Brilliant!

What have the Romans done for us? For one thing, they invented data-storing tablets which required neither batteries nor wireless connections!

@Albertus Minimus: but they do require decoding, microscopic technology, etc, lol. I guess modern tablets and wax tablets each have their pros and cons 🙂