The British Library’s Discovering Literature project, a website with selections of exceptional works from its collections digitized, explicated by experts with multimedia aides and resources for teachers, has added a new subsection dedicated to its medieval literary treasures. Discovering Literature: Medieval submits for your approval/devouring 50 digitized manuscripts and early printed books dating from the 8th to 16th centuries. These rare volumes are some of the most influential works in the history of English literature.

The British Library’s Discovering Literature project, a website with selections of exceptional works from its collections digitized, explicated by experts with multimedia aides and resources for teachers, has added a new subsection dedicated to its medieval literary treasures. Discovering Literature: Medieval submits for your approval/devouring 50 digitized manuscripts and early printed books dating from the 8th to 16th centuries. These rare volumes are some of the most influential works in the history of English literature.

There’s The Wycliffite Bible, the first complete translation of the Bible into English, Revelations of Divine Love by Julian of Norwich, the first work written by a woman in English, the first autobiography in English (The Book of Margery Kempe) and the only surviving Old English manuscript of Beowulf which somehow avoided the fate of so many priceless works of literature in the Robert Cotton collection that burned to ashes in a devastating October 23rd, 1731, conflagration at the aptly named Ashburnham House.

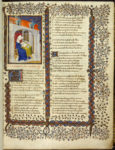

There’s The Wycliffite Bible, the first complete translation of the Bible into English, Revelations of Divine Love by Julian of Norwich, the first work written by a woman in English, the first autobiography in English (The Book of Margery Kempe) and the only surviving Old English manuscript of Beowulf which somehow avoided the fate of so many priceless works of literature in the Robert Cotton collection that burned to ashes in a devastating October 23rd, 1731, conflagration at the aptly named Ashburnham House.  William Caxton’s illustrated early print edition of The Canterbury Tales may not have the color and beauty of the hand-illuminated The Book of the Queen by Christine de Pizan (the first woman author to actually make a living on the income from her writing), but it was a groundbreaking advance for the dissemination of literature and literacy.

William Caxton’s illustrated early print edition of The Canterbury Tales may not have the color and beauty of the hand-illuminated The Book of the Queen by Christine de Pizan (the first woman author to actually make a living on the income from her writing), but it was a groundbreaking advance for the dissemination of literature and literacy.

Digital technology puts all of these rare or unique masterpieces, some of which aren’t even available to scholars, at our fingertips. The sole surviving manuscript of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, for example, one of the greatest works of Middle English poetry, is so fragile after having barely escaped the same fire that almost incinerated Beowulf, that our grubby hands wouldn’t be allowed anywhere near it. Now we can enjoy its glories while smearing inches of caked Cheeto dust on our mice without a care in the world.

Digital technology puts all of these rare or unique masterpieces, some of which aren’t even available to scholars, at our fingertips. The sole surviving manuscript of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, for example, one of the greatest works of Middle English poetry, is so fragile after having barely escaped the same fire that almost incinerated Beowulf, that our grubby hands wouldn’t be allowed anywhere near it. Now we can enjoy its glories while smearing inches of caked Cheeto dust on our mice without a care in the world.

If your ability to read manuscripts and early print of Old and Middle English is a bit rusty, allow the more than 20 articles written by academics, poets, authors in their own right, to help you understand what you’re seeing and the impact it had on its time and ours. Or rifle through the associated collection items. There are some fantastic maps. The Beatus World Map with its remarkably modern abstract graphic is a particular favorite of mine.

If your ability to read manuscripts and early print of Old and Middle English is a bit rusty, allow the more than 20 articles written by academics, poets, authors in their own right, to help you understand what you’re seeing and the impact it had on its time and ours. Or rifle through the associated collection items. There are some fantastic maps. The Beatus World Map with its remarkably modern abstract graphic is a particular favorite of mine.

When you’re done getting your Gawain and Beowulf on, you can lose more hours, days, weeks of your life perusing the Romantics and Victorians section. It features more than 1,200 items from the BL’s collection from first edition published books to diaries, advertisements, penny dreadfuls, illustrations, manuscripts, pamphlets, letters and so much more. On top of the period items, you can enjoy more than 150 articles written by scholars about the works in the collection and 25 documentary films. For the educators among us, there are 30 teachers’ notes good to go. It’s like college, seriously.

Discovering Literature is an unparalleled resource, a way of making an enormous collection like the British Library’s, a feast beyond any normal individual’s ability to ingest, never mind digest, accessible to everyone. It’s not dumbed down or meager. It’s just curated carefully to convey a wealth of information in concentrated form. Already so successful in its aims, this project is still just revving up. More content is added all the time.

Here’s a link to the website:

https://www.bl.uk/discovering-literature

There are always those people who bang on and on about the importance of teaching kings names and dates – but I just wanted the stories like Beowulf and weird maps. It is probably why stories like The Hobbit outsell history books.

Oh my goodness. The Romantics and Victorians section has 1,200+ items including published books to diaries, illustrations, manuscripts, letters etc!! I would never get out of the place, even before I found any scholarly articles about the literature.

At school the gap between Chaucer and Shakespeare was filled for us by Robert Henryson and especially William Dunbar, whom I remember enjoying. Therefore did I entype his name and thereunto did appear …….

https://www.bl.uk/medieval-literature/articles/the-makars-medieval-scottish-poetry

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/bannatyne-manuscript

Mind you, I have to grin at someone who feels that the following needs translation:

…“My sone, lat be,

For quhat is it worth to tell ane fenyeit taill

Quhen haly preiching may nathing auaill?”

If, dear reader, you don’t know any Dunbar, try this ‘un.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44205/lament-for-the-makers-56d22335db2cd

Aye, – Sone, what about.. ? 😉

—————–

Yr auld storeis befoir thir mony yeir,

Thai war distroyit all with Inglismen,

In Wallace weir as it eith to ken,

Syne efterwart, quhen that thai wreit historie,

Auld eldaris deidis put into memorie …

—————–