The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art in Winter Park, Florida, is home to the world’s most comprehensive collection of works by Louis Comfort Tiffany, encompassing everything from lamps, vases and jewelry to windows, the incredible Daffodil Terrace and even the entire chapel he created for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Now to that great variety of masterpieces the museum has added a unique cast iron fireplace hood (pdf) that Tiffany so loved it lived in two houses with him.

Louis Comfort Tiffany was a passionate collector of Chinese and Japanese art, and Asian motifs inspired many of his works (bat lamp 4eva!). His New York City home on 72nd Street and Madison, and later his Long Island country estate Laurelton Hall, were replete with Japanese and Chinese antiquities, rugs, furniture, ukiyo-e woodblock prints, pottery, statues, screens, musical instruments, jade cups, textiles, hairpins, beads, tea caddies, leather tobacco pouches, lacquer boxes, incense burners, weapons, multiple complete sets of samurai armor and much more, an impossibly wide assortment of objects large and small. Tiffany’s Asian collection crowded every nook, corner and surface of Laurelton Hall, not just the two dedicated rooms — the Chinese Room and the Japanese Room.

After the Meiji government of Japan abolished the samurai class in the 1870s, specifically outlawing the wearing of swords in 1876, Western auction houses made a brisk business of selling samurai armature. Louis Comfort Tiffany began collecting samurai sword guards (tsuba) in the 1880s. They flooded the market at that time, and Tiffany bought them literally by the barrel. In 1882 he  acquired 2,500 in one fell swoop from his design firm partner Lockwood de Forest. They ranged in date from the late 18th to the early 19th centuries. Most of them were made of punched or pierced iron, some also decorated with mother-of-pearl and metal inlays in natural motifs (chrysanthemums, dragonflies). He was charmed by their fine workmanship, smooth curves, openwork textures and variety as each were individually made and no two sword guards were alike. He was known to carry one in his waistcoat pocket at all times.

acquired 2,500 in one fell swoop from his design firm partner Lockwood de Forest. They ranged in date from the late 18th to the early 19th centuries. Most of them were made of punched or pierced iron, some also decorated with mother-of-pearl and metal inlays in natural motifs (chrysanthemums, dragonflies). He was charmed by their fine workmanship, smooth curves, openwork textures and variety as each were individually made and no two sword guards were alike. He was known to carry one in his waistcoat pocket at all times.

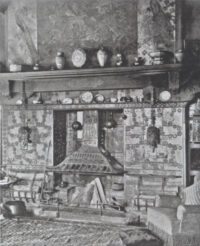

With such a bounty of them, he incorporated tsuba in pieces of his own manufacture, including lampshades, frames of stained glass windows and suspension chains for hanging light fixtures. He embedded them into wine casks that he then mounted on the wall of the breakfast room. Around 1883, 14 years before he would open a foundry and metal shop to manufacture brass, bronze, copper and iron fittings for his glassworks in Corona, Queens, Louis Comfort Tiffany created a cast iron smoke hood in his Fourth  Street workshops. It was 66 inches tall and 55 inches wide with tsuba embedded onto it so artfully their openwork looks like it is cut directly out of the hood itself. He mounted the smoke hood over the fireplace of the library in his 72nd Street home. More tsuba decorated the chimney breast, flanking walls and the fender. Pairs of them lined the vertical dividers between the five stained glass Magnolia panels of the bay window.

Street workshops. It was 66 inches tall and 55 inches wide with tsuba embedded onto it so artfully their openwork looks like it is cut directly out of the hood itself. He mounted the smoke hood over the fireplace of the library in his 72nd Street home. More tsuba decorated the chimney breast, flanking walls and the fender. Pairs of them lined the vertical dividers between the five stained glass Magnolia panels of the bay window.

The hood remained in place until 1919, the year Louis retired from Tiffany Studios, when he dismantled it from his Manhattan home and reinstalled it in the smoking room of Laurelton Hall. The smoking room contained approximately 2,000 tsuba, not counting the ones he’d used to make custom pieces. The ones that weren’t soldered to lampshades and fireplace hoods he kept in wood cabinets.

Louis Comfort Tiffany had hoped that Laurelton Hall would become an enduring testament to his aesthetic vision long after he was gone, but the endowment he established to support Laurelton as a museum after his death in 1933 fell victim to financial reversals. The foundation was forced to sell the contents of the house at a Park-Bernet auction in 1946. The mansion with its 84 rooms, outbuildings, and 60 acres was sold and subdivided. Already much degraded, Laurelton Hall was all but destroyed by fire in 1957.

Louis Comfort Tiffany had hoped that Laurelton Hall would become an enduring testament to his aesthetic vision long after he was gone, but the endowment he established to support Laurelton as a museum after his death in 1933 fell victim to financial reversals. The foundation was forced to sell the contents of the house at a Park-Bernet auction in 1946. The mansion with its 84 rooms, outbuildings, and 60 acres was sold and subdivided. Already much degraded, Laurelton Hall was all but destroyed by fire in 1957.

Hugh F. McKean, whom Louis Comfort Tiffany had invited to live at Laurelton as artist-in-residence in 1930, bought basically everything that survived the fire. Hugh’s wife Jeannette Genius McKean had founded the Morse Museum in 1942 in honor of her grandfather, machinery manufacturer and philanthropist Charles Hosmer Morse. When Laurelton Hall burned down, she and Hugh visited the ruins. She told him, “Let’s buy everything that is left and try to save it,” and that’s exactly what they did. The Morse Museum’s unparalleled Louis Comfort Tiffany collection is the result.

They did not salvage the iron hood from the smoking room, however. It was presumed destroyed. When it turned up in New York last year, the Morse Museum snapped it up with a quickness. The museum’s collection of objects, architectural features, furnishings and materials from Laurelton Hall, the largest in the world, is displayed in a dedicated 12,000-square-foot wing. The iron fireplace hood will join its brethren in the Laurelton Gallery on October 20th of this year.

Wonder who took it after the fire. Will other ‘found’ items show up?

I’m curious about that as well and have asked the museum’s press rep if they know what happened to it between the fire and the acquisition. Vultures (human ones) definitely descended on Laurelton Hall after the fire, looking for treasures in the debris. You wouldn’t think that such a huge, heavy piece would be lootable, though.

The exact ownership history is not known, but it seems some of the salvaged objects were sold to Tiffany’s Long Island neighbors, in this case Rayburn Burgess. It was never offered to the McKeans. A large and heavy iron feature like this would be a lot easier to schlep next door than to Florida.

As a blacksmith I can say that the hood looks much more like wrought iron (pieces heated and vent or formed and then assembled) than cast iron (molten metal poured into a mold. There is faux wrought iron which is cast but this does not look like it at all.

It would be interesting to see how the tsubas are attached to the hood. I suspect that holes were made in the side plate and then carefully filed to fit each tsuba and they were then either soldered in from the back or there are clips on the inside holding them in place.

This hood is unusual because I don’t recall L.C, Tiffany otherwise working in or directing work in a base metal like this.

“By hammer and hand all arts do stand.”

I’ve been a blacksmith off and on for more than 50 years. This hood is NOT cast iron, it is wrought iron.

The iron has been bent and formed hot. Casting these large thin curved and curled forms in iron would be extraordinarily difficult.

The joinery is riveted, folded and crimped.

There is also an example of repoussee in the upper right of the transition from hood to smoke stack. Shown in a photo not in this article.

In the same general location shown in this article there appear to be chased elements, designs incised with chisels. A technique unsuited to cast iron, especially not in such thin sections.

I recommend you have an experienced blacksmith examine the piece. I’ve been mistaken before but strongly doubt it in this case. As a last note, your museum is now on my bucket list.

Thank you for saving his works.

I have been a blacksmith off and on for more than 50 years. This hood is NOT cast iron, it is wrought iron.

The iron has been bent and formed hot. Casting these large thin curved and curled forms in iron would be extraordinarily difficult.

The joinery is riveted, folded and crimped.

There is also an example of repousee in the upper right of the transition from hood to smoke stack. Shown in a photo not in this article.

In the same general location shown in this article there appear to be chased elements, designs incised with chisels. A technique unsuited to cast iron, especially not in such thin sections.

I recommend you have an experienced blacksmith examine the piece. I’ve been mistaken before but strongly doubt it in this case. As a last note, your museum is now on my bucket list.

Thank you for saving his works.

Fascinating analysis, thank you very much for it. I’ve relayed yours and George’s comments to the Morse Museum press contact and she has asked the curator and collections manager for clarification on how the iron was worked. :thanks:

I hope it gets corrected as it’s like going into a Museum and seeing oil paintings described as “watercolors”. Different materials worked in different ways and recognizable on sight to anyone who is familiar with either or both of the different techniques required by the different materials.

As a collector of Japanese arms and armor those photos are horrifying to me. That’s all I’ll say.