When the rise of digital photography and a Ponzi scheme at its parent company killed the Polaroid star, a north Minnesota bankruptcy court hearing the case ordered the Polaroid Corporation’s extensive and venerable photography collection to go under the hammer, with all proceeds used to pay creditors. Sotheby’s is thrilled to the tips of its toesies to put some of the collection on sale on Monday and Tuesday. Meanwhile, they’ve selected 1,200 of the most notable photographs to go on display in their Manhattan offices. Admission is free.

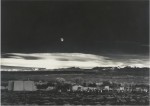

The collection stars some of the greatest luminaries of American photography: Ansel Adams, Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, William Wegman and his Weimaraners, even Robert Mapplethorpe and Andy Warhol. Ansel Adams was a close friend and collaborator of Edwin Land, eccentric genius and inventor of the Polaroid instant developing technology. They worked together for decades experimenting with film and cameras, and to build the collection.

The collection stars some of the greatest luminaries of American photography: Ansel Adams, Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, William Wegman and his Weimaraners, even Robert Mapplethorpe and Andy Warhol. Ansel Adams was a close friend and collaborator of Edwin Land, eccentric genius and inventor of the Polaroid instant developing technology. They worked together for decades experimenting with film and cameras, and to build the collection.

It’s the finest group of Ansel Adams prints in private hands, according to the Sotheby’s expert.There 400 of his pictures are in the auction, many of them taken with Polaroid cameras or film. Some are mural-sized and expected to fetch in the neighborhood of half a million dollars. Others are palm-sized snapshots like the ones all we old folks who were alive before the millennium know and love.

In fact, most of the pictures in the collection were taken with Polaroids. The ones that aren’t were personally collected by Ansel Adams at Land’s behest. They wanted to ensure the collection didn’t become overly narrow and that it would display a range of photographic techniques, so Land gave Adams a stipend to purchase pictures from his friends and colleagues to create what would become known as the Library Collection, a group of non-Polaroid pictures by masters like William Garnett and Minor White.

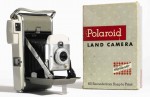

It’s the Polaroid pieces that really stun and amaze me, however. The technology has so much more breadth than I realized. Inspired by his daughter’s disappointment that she could not see the picture he had taken of her on vacation in New Mexico in 1943 right away, Land invented a way to develop a negative into a positive before our very eyes. The first Polaroid instant camera, the Land Camera, went on sale in 1948 and it was a huge hit.

It’s the Polaroid pieces that really stun and amaze me, however. The technology has so much more breadth than I realized. Inspired by his daughter’s disappointment that she could not see the picture he had taken of her on vacation in New Mexico in 1943 right away, Land invented a way to develop a negative into a positive before our very eyes. The first Polaroid instant camera, the Land Camera, went on sale in 1948 and it was a huge hit.

The SX-70, Land’s most popular camera [first sold in 1972], was as convenient as a mobile phone, folding flat so it could be stuffed in a pocket. Its styling – a skin of brushed aluminium with a panel of inlaid leather – flattered the user, advertising modernity while hinting at gentility. Like all good, exploitable ideas, this one had to be constantly reinvented so that consumers did not become bored. Although Land began by selling the Polaroid as something anyone could and should own, he also shrewdly fetishised his product, dreaming up ever more complicated cameras and engaging celebrated photographers to test them.

At first, Polaroid’s appeal lay in its portability and simplicity. But American entrepreneurs think big. Land went on to design a 20in by 24in camera, which had to be cumbersomely transported to the artists who were chosen to use it: manoeuvred into the New York apartment of Lucas Samaras; freighted to Robert Rauschenberg in Florida. By the 1980s Land had come up with a 40in by 80in camera, an immovable piece of furniture that was permanently domiciled at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where it made life-sized reproductions of paintings on single sheets of Polacolor film. The photographers who experimented with it, including Samaras, needed to engage assistants who actually sat inside it. Camera comes from the Latin for “chamber”, and this one – belying the pocket-sized handiness of the early models – was a virtual room.

Land made offers artists couldn’t refuse: he’d let them use his wild and appealing equipment if they’d give him the pictures they took. Polaroid got licensing and published rights, but the artists still retained their copyrights and exclusive access to their work. In this way Land built a corporate collection that was and remains a marvel of creative, unique artistry.

Some of the artists are furious at the sale, not surprisingly. The deals they struck with Land are not enforceable once the pieces are purchased by third parties.

Now that the collection is to be sold off, the terms of this deal have been questioned, and there may yet be a legal challenge to the sale. A federal judge in Oklahoma is rallying protest, pointing out that the bankruptcy court didn’t appreciate that Polaroids are unique, which means that the photographers will forfeit their right of access when their images are in private hands. The painter Chuck Close, who made a series of collaged self-portraits with the 20 by 24 camera, has denounced the sale as “criminal”. But so far, as Sotheby’s rather smugly announced a while ago, no photographer has made a legitimate case for the return of items destined for the block.

So the hammer will fall and the Polaroid Collection, lovingly curated by geniuses Edwin Land and Ansel Adams, will be dispersed all over the world. You can browse the e-catalogue on the Sotheby’s site to get a glimpse at the magnitude of this special collection.

For a riveting overview of the art and technology of the Polaroid Collection, please watch this video produced by Sotheby’s:

[flashvideo file=http://www.thehistoryblog.com/wp-content/videos/Sothebys_Polaroid_collection.flv width=427 height=242 /]

What I do have is the camera that made the Polaroid photo of the Lifesaver add that was in very large format (Polaroid Vectograph) and mounted in Times Square NY in 1930s. It is a stereo graphic acquired from Photographer that took the photo for Polaroid.I was checking the auction & other info on Polaroid collection to see if it was still in collection.

Dick

Did you find out?