A wooden galleon that won the southwestern Italian city of Amalfi its first victories in a regatta against its ancient maritime rivals has been restored to its former vividly-colored glory. The painstaking restoration was revealed in a ceremony that reunited the victorious crews who famously rowed Vittoria to, well, victory.

A wooden galleon that won the southwestern Italian city of Amalfi its first victories in a regatta against its ancient maritime rivals has been restored to its former vividly-colored glory. The painstaking restoration was revealed in a ceremony that reunited the victorious crews who famously rowed Vittoria to, well, victory.

The Regatta of the Ancient Maritime Republics was a plan hatched by Venice, Genoa, Pisa and Amalfi to put on a history-flavored pageant to attract tourists the way the Palio of Siena attracts tourism. From the Middle Ages on, they were the four pre-eminent medieval port city-states in Italy, so iconically connected to maritime power that in 1947 their coat of arms were combined to create the coat of arms of the Navy of the Italian Republic. In 1949, representatives of the four cities met and ultimately agreed to establish a yearly boat race in which each city would field a crew of eight rowers and a helmsman from among its own residents. Each city would alternate hosting the race over a two-kilometer course. Amalfi’s course is the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea.

The boats were built to precise specifications and painted in their cities’ colors. The figurehead on the prow of the ship was the city’s symbol: a winged horse for Amalfi, dragon for Genoa, eagle for Pisa and the winged lion for Venice. The figureheads also play a key role in determining the winner, as the jury decides which boat won by judging whether the furthest forward point cut the finish line first. For Amalfi it’s the tip of Pegasus’ front hoof.

The boats were built to precise specifications and painted in their cities’ colors. The figurehead on the prow of the ship was the city’s symbol: a winged horse for Amalfi, dragon for Genoa, eagle for Pisa and the winged lion for Venice. The figureheads also play a key role in determining the winner, as the jury decides which boat won by judging whether the furthest forward point cut the finish line first. For Amalfi it’s the tip of Pegasus’ front hoof.

The first ships were made of wood by the Gondolieri Cooperative of Venice. The Vittoria was the second ship made for Amalfi and it brought it nothing but luck, winning the Regatta in 1975, 1979 and 1981. This was a big deal for Amalfi, because the other three Maritime Republics had won repeatedly in the 19 regattas between 1956 and 1974. Venice dominated with 14 wins. Genoa won three times and Pisa managed to get on the board with two first-place finished. Before the Vittoria‘s hoof cut the finish line in 1975, Amalfi had never come in first. It had never even come second. It only came third once in 1957, so basically Amalfi spent two decades firmly ensconced in last place.

The losing streak was broken in the 1975 regatta held in Pisa. Pisa was lucky for Amalfi’s team again in the 1979 race, and then in 1981, they hit the dream combination: they won first place when they were hosting. Those three victories in six years had to keep Amalfi warm for the next 14 years of losses before they reclaimed the title three times in a row between 1995 and 1997, but by then the wooden boats had been replaced by fiberglass, so the Vittoria was not involved.

It was abandoned and left exposed to the elements, so even though it’s not that old in the scale of Maritime Republics, it was already on the brink of decay. It was restored thanks to a private donor Dr. Claudio Marciano di Scala who funded a complete restoration including replacement of all rotted topside elements with prized materials like Douglas fir and mahogany. The brilliantly-colored paint colors were reapplied with traditional methods.

The medievalist prof. Giuseppe Gargano who provided a series of indications to the shipwrights, also of a historical nature: “With the restoration of the galleon, it was also possible to solve a problem linked to its decorations, i.e. the six shields which adorn the stern castle,” he explained last night. “We wanted to give order and clarity to the symbols so as to offer visitors the possibility of better understanding some dynamics in the evolution of civic symbology. Starting with the flag of the city and the duchy of Amalfi, adopted in 1266 with the adhesion to the Angevin cause up to the black and white shield (day and night), charged by a winged compass and a comet, dating back to century and which was first the coat of arms of the Principality of Citra and then of the Province of Salerno. It was applied to the lower section of the Amalfi municipal coat of arms during the 14th century. Finally, the octagonal cross on a black background, the ancient symbol of the Order of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, founded by Blessed Gerardo Sasso of Scala.”

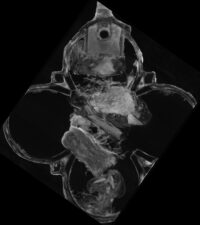

The Vittoria is now on permanent display in Amalfi’s spectacular Arsenale, a masonry cross-vaulted shipyard built on the seafront in the 11th century. It first appears on the historical record in 1059, seven years before the Norman Conquest, a thousand years later, it is still in its original condition. It hasn’t been destroyed, rebuilt, quarried or tampered with in any way and there is no other example of medieval architecture like it in the world.

The cross is a foot long from top to bottom and is adorned with more crosses. There are Canterbury crosses 4 cm (1.6 inches) wide at the end of the cross-arms arm and the bottom of the descending arm. At the center point of the crossarm is an equal-armed cross 8 cm (3.15 inches) wide. Between each of the arms of the central cross are oval human faces cast in silver with blue glass eyes.

The cross is a foot long from top to bottom and is adorned with more crosses. There are Canterbury crosses 4 cm (1.6 inches) wide at the end of the cross-arms arm and the bottom of the descending arm. At the center point of the crossarm is an equal-armed cross 8 cm (3.15 inches) wide. Between each of the arms of the central cross are oval human faces cast in silver with blue glass eyes. The burial dates to between 630 and 670 A.D. At that time, Harpole was part of the Kingdom of Mercia which was smack in the middle of converting to Christianity. The first introduction of Christianity to Mercia came in 628 when the pagan King Penda conquered Christian Saxon-held territories. Penda’s son Peada sealed the deal in 655 when he converted to Christianity and agreed to evangelize and convert his subjects as a condition of his marriage to Alchflaed, the daughter of King Oswiu of Northumbria.

The burial dates to between 630 and 670 A.D. At that time, Harpole was part of the Kingdom of Mercia which was smack in the middle of converting to Christianity. The first introduction of Christianity to Mercia came in 628 when the pagan King Penda conquered Christian Saxon-held territories. Penda’s son Peada sealed the deal in 655 when he converted to Christianity and agreed to evangelize and convert his subjects as a condition of his marriage to Alchflaed, the daughter of King Oswiu of Northumbria.