A treasure hailed as the “gold find of the century in Norway” has been discovered by a metal detectorist in Rennesøy, an island in southwestern Norway. The group of gold bracteates and beads dates to the late Migration Period (375-568 A.D.), and is believed to have been part of a single opulent necklace.

A treasure hailed as the “gold find of the century in Norway” has been discovered by a metal detectorist in Rennesøy, an island in southwestern Norway. The group of gold bracteates and beads dates to the late Migration Period (375-568 A.D.), and is believed to have been part of a single opulent necklace.

Erlend Bore picked up metal detecting when his physiotherapist and doctor strongly recommended he get outside more to combat the ills of sedentary living. On June 7th, he took his new metal detector out for its first spin. Two months later, he went to Rennesøy. When his detector gave a strong signal, he lifted a clod of earth and saw a glitter that he thought was a wrapper for a chocolate coin. Reader, it was not a chocolate wrapper. Bore scooped it up to take a closer look and when the soil around it fell apart, even more gold beads came out.

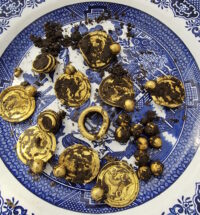

He immediately contacted the county archaeologist and sent him a picture of the find. The archaeologist informed him he had found Migration Era gold treasure. The find consists of nine gold bracteates (flat, thin, single-sided medallions that never circulated as actual coins but were often modelled after coins), all of them bearing a stylized horse image, ten gold beads and three gold spiral rings. The total gold weight of the find is just over 100 grams.

He immediately contacted the county archaeologist and sent him a picture of the find. The archaeologist informed him he had found Migration Era gold treasure. The find consists of nine gold bracteates (flat, thin, single-sided medallions that never circulated as actual coins but were often modelled after coins), all of them bearing a stylized horse image, ten gold beads and three gold spiral rings. The total gold weight of the find is just over 100 grams.

Archaeologists believe the gold necklace and spiral rings were buried in the 6th century during a time of conflict, plague and upheaval after a volcanic eruption blocked out of the sun in 535-6 A.D. leading to widespread crop failure and famine. Ole Madsen, director of the Archaeological Museum at the University of Stavanger, called the treasure “the gold find of the century” because it has been that long since so many pieces of gold jewelry have been found together in one place in Norway. The bracteates alone, however, would be sufficient to garner such high praise.

Archaeologists believe the gold necklace and spiral rings were buried in the 6th century during a time of conflict, plague and upheaval after a volcanic eruption blocked out of the sun in 535-6 A.D. leading to widespread crop failure and famine. Ole Madsen, director of the Archaeological Museum at the University of Stavanger, called the treasure “the gold find of the century” because it has been that long since so many pieces of gold jewelry have been found together in one place in Norway. The bracteates alone, however, would be sufficient to garner such high praise.

Professor Sigmund Oehrl at the Archaeological Museum is an expert on bracteates and their symbols. Approximately 1,000 golden bracteates have so far been found in Scandinavia. According to him, the gold pendants from Rennesøy are of a specific type that is very rare. They show a horse motif in a hitherto unknown form.

“The motifs differ from most other gold pendants that have been found so far. The symbols on the pendants usually show the god Odin healing the sick horse of his son Balder. In the Migration Period, this myth was seen as a symbol of renewal and resurrection, and it was supposed to give the wearer of the jewelery protection and good health,” says Oehrl.

On the Rennesøy bracteates, however, only the horse is depicted. A somewhat similar horse, depicted together with snake-like monsters, is also found on a pair of gold bracts found in Rogaland and southern Norway.

“On these gold pendants the horse’s tongue hangs out, and its slumped posture and twisted legs show that it is injured. Like the Christian symbol of the cross, which spread in the Roman Empire at exactly this time, the horse symbol represented illness and distress, but at the same time hope for healing and new life,” says Oehrl.

The bracteates, beads and spirals are now being conserved at the Archaeological Museum at the University of Stavanger and will soon go on display. According to Norwegian law, any archaeological object dating before 1537 belongs to the state. The finder and the landowner will split a finder’s fee in an amount determined by the National Antiquities Authority.