I can never get enough videos of conservators bathing a large but fragile historic tapestry ever so gently like it’s a little baby. This time the tapestry in question is “King Arthur” from the “Nine Heroes Tapestries” series that is in The Cloisters, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s branch dedicated to medieval art.

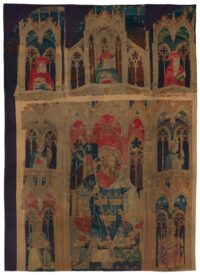

In this tapestry, King Arthur sits on a throne under a canopy accompanied by two bishops on the bottom row, two archbishops in the middle and three cardinals on balcony overlooking them. They are set in a capriccio of Gothic architecture complete with tracery windows, pointed arches, rib vaulting and elaborate spires. The clothing and architecture is typical of around 1400.

The series was woven in the late 14th century is the South Netherlands and are some of the oldest surviving tapestries from the Middle Ages. They depict nine famous heroes, also known as the Nine Worthies, drawn from literature, history and scripture that were believed to embody the ideals of chivalry. They are Prince Hector of Troy, Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Joshua, David, Judas Maccabeus, King Arthur, Charlemagne and Godfrey of Bouillon (a French nobleman who became the first King of Jerusalem after he captured it in the First Crusade in 1099). Originally the nine heroes were woven into three separate tapestries, three on each, grouped by religion (pagan heroes on one, Jewish heroes on another, Christians on the third), but by the time they entered the Met’s collection in 1947, only five heroes had survived. It’s a miracle there are any left at all given the rough treatment they received. At some point they were cut up in dozens of pieces and survived as Frankenstein monsters of their former selves, the fragments stitched together in the early 20th century to be hung as curtains in an castle in France.

The Met’s curators were able to figure out how to puzzle the tapestries back together working only with photographs, but even with the jigsaw solved on paper, the hard work of disassembling and reassembling was still to be done. The museum engaged four women with great needle skills to transform those curtains back into plausible tapestries. They were Mathilda Sullivan, Helen O’Brien, Swiss immigrant Aline von Arx and Norwegian immigrant Olga Wangen Larsen. Restoration work began in December 1947 with Sullivan buying the wool threads they would need and was completed on May 15th, 1949, literally four days before they went on display for the first time in their new gallery at The Cloisters. Collectively the four worked just shy of 6,000 hours to piece the heroes back together.

None of the Nine Heroes series have received conservation treatment since 1949, and they are now in need of cleaning and stabilization. The cut-and-paste life they’ve led for centuries makes them extremely delicate, so the fewer interventions the better. “King Arthur” is the first of the series to be conserved. The rest will follow in his footsteps while conservators use the knowledge they’ve gained in this intervention to aid in the next.