A mound at Leka in central Norway has been identified as a ship burial constructed in the Merovingian era (550-800 A.D.), predating the Viking era by a hundred years. Radiocarbon dating results indicate the mound was built around 700 A.D., making it the oldest known ship burial in Scandinavia.

A mound at Leka in central Norway has been identified as a ship burial constructed in the Merovingian era (550-800 A.D.), predating the Viking era by a hundred years. Radiocarbon dating results indicate the mound was built around 700 A.D., making it the oldest known ship burial in Scandinavia.

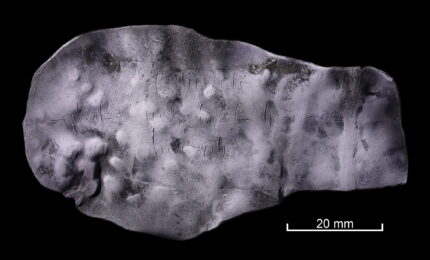

The Herlaugshaugen mound was surveyed this summer by archaeologists and volunteer metal detectorists at the behest of national and county heritage authorities. The team recovered large iron rivets, some with wood corroded around them, confirming that the mound contained a ship burial.

“This dating is really exciting because it pushes the whole tradition of ship burials quite far back in time,” said Geir Grønnesby, an archaeologist at the NTNU University Museum. […]

The development of shipbuilding has played a key role in the discussion about when and why the Viking Age started. We can’t say that the Viking Age started earlier based on this dating, but Grønnesby says that you don’t build a ship of this size without having a reason for doing so.

“The burial mound itself is also a symbol of power and wealth. A wealth that has not come from farming in Ytre Namdalen. I think people in this area have been engaged in trading goods, perhaps over great distances.”

The mound is located along a shipping route that at least from the mid-8th century was a key stop in the trade of whetstones to mainland Europe, so it stands to reason that the locals could have had the knowledge, skills and incentive to build large ships.

The mound is located along a shipping route that at least from the mid-8th century was a key stop in the trade of whetstones to mainland Europe, so it stands to reason that the locals could have had the knowledge, skills and incentive to build large ships.

At 200 feet in diameter, Herlaugshaugen is one of the largest burial mounds in Norway. It was first excavated in the late 18th century. Those early excavations reportedly unearthed a bronze cauldron, animal bones, iron nails and most dramatically of all, a seated skeleton with a sword. The finds were lost, disappearing from view in the 1920s. The skeleton, also missing, was exhibited as the semi-legendary 9th century king Herlaug, after whom the mound was named.

According to the Heimskringla, the collection of sagas of the kings of Norway by 13th century chronicler Snorri Sturlason, Herlaug and his brother Hrollaug co-ruled the petty kingdom of Naumudal, north of Trondheim, in the 860s A.D. The minor kingdoms were constantly squabbling with each other, and in 866 A.D., Harald Hårfagre, king of Agder, started a campaign to defeat them all and unite Norway under his rule. Many kinglets went down to defeat. After his conquest of Trondheim, the brother kings knew they were next. They had very different reactions to the news.

According to the Heimskringla, the collection of sagas of the kings of Norway by 13th century chronicler Snorri Sturlason, Herlaug and his brother Hrollaug co-ruled the petty kingdom of Naumudal, north of Trondheim, in the 860s A.D. The minor kingdoms were constantly squabbling with each other, and in 866 A.D., Harald Hårfagre, king of Agder, started a campaign to defeat them all and unite Norway under his rule. Many kinglets went down to defeat. After his conquest of Trondheim, the brother kings knew they were next. They had very different reactions to the news.

North in Naumudal were two brothers, kings,—Herlaug and Hrollaug; and they had been for three summers raising a mound or tomb of stone and lime and of wood. Just as the work was finished, the brothers got the news that King Harald was coming upon them with his army. Then King Herlaug had a great quantity of meat and drink brought into the mound, and went into it himself, with eleven companions, and ordered the mound to be covered up. King Hrollaug, on the contrary, went upon the summit of the mound, on which the kings were wont to sit, and made a throne to be erected, upon which he seated himself. Then he ordered feather-beds to be laid upon the bench below, on which the earls were wont to be seated, and threw himself down from his high seat or throne into the earl’s seat, giving himself the title of earl. Now Hrollaug went to meet King Harald, gave up to him his whole kingdom, offered to enter into his service, and told him his whole proceeding. Then took King Harald a sword, fastened it to Hrollaug’s belt, bound a shield to his neck, and made him thereupon an earl, and led him to his earl’s seat; and therewith gave him the district Naumudal, and set him as earl over it.

The newly-discovered date means the skeleton found within was not in fact Herlaug, but rather an elite individual who died close to two centuries before the king of lore sealed himself into his own tomb in a final act of defiance.