Fishermen in Wales have discovered fishing baskets thought to be at least 600 years old in the Severn Estuary. Black Rock Lave Net fishermen found the baskets off the coast of Portskewett while walking their fishing grounds at low tide in the off season. The baskets had been preserved for centuries, buried in the silt and sand of the riverbank, and were only exposed by a recent storm.

Fishermen in Wales have discovered fishing baskets thought to be at least 600 years old in the Severn Estuary. Black Rock Lave Net fishermen found the baskets off the coast of Portskewett while walking their fishing grounds at low tide in the off season. The baskets had been preserved for centuries, buried in the silt and sand of the riverbank, and were only exposed by a recent storm.

This isn’t the first time the group have found artefacts such as these. However, as Martin Morgan, secretary of the fishery, explained, it is unusual to uncover so many baskets grouped together.

Mr Morgan said: “The baskets would have been baited and pegged to the estuary bed at low tide. The catch would have been green eels and lamprey.

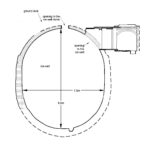

“They are made of willow and hazel in an urn shape with a non-return built into the neck. The overall length is around two feet.”

They haven’t been dated yet, but baskets found before in that spot were radiocarbon dated by Reading University researchers to between the 12th and 15th centuries. The design is also characteristic of baskets from that era. The finders hope to get the newly-discovered baskets dated as well, but it’s a race against time because the wood deteriorates rapidly once it’s exposed to the air.

It is eminently fitting that these particular fishermen would recover ancestral tools of their trade. The Black Rock Lave Net Fishery is the last traditional salmon fishery left on Wales’ side of the Severn Estuary. The lave net method they employ — wading or boating into the shallow coastal waters and catching fish using hand-woven nets attached to wood poles — has been used on the estuary since at least the 17th century, and likely earlier. Basket fishing is older, but it was in use for an incredibly long time. The last basket fishery on the estuary closed in 1995, believe it or not.

It is eminently fitting that these particular fishermen would recover ancestral tools of their trade. The Black Rock Lave Net Fishery is the last traditional salmon fishery left on Wales’ side of the Severn Estuary. The lave net method they employ — wading or boating into the shallow coastal waters and catching fish using hand-woven nets attached to wood poles — has been used on the estuary since at least the 17th century, and likely earlier. Basket fishing is older, but it was in use for an incredibly long time. The last basket fishery on the estuary closed in 1995, believe it or not.

This wonderful video documents the work of lave net fishermen today. It truly is living history.