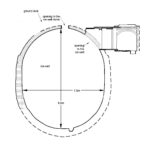

A large ice house from the late 18th century has been unearthed by buildings archaeologists in central London. Discovered off of Regent’s Park, the Ice House is more than 24 feet wide and 31 feet deep. It is an egg-shaped cupola made of red brick and is in outstanding condition. Even the entrance passage and vaulted antechamber survive intact, unmolested by active construction of massive buildings in the early 19th century and the destruction of a great deal of London during World War II.

A large ice house from the late 18th century has been unearthed by buildings archaeologists in central London. Discovered off of Regent’s Park, the Ice House is more than 24 feet wide and 31 feet deep. It is an egg-shaped cupola made of red brick and is in outstanding condition. Even the entrance passage and vaulted antechamber survive intact, unmolested by active construction of massive buildings in the early 19th century and the destruction of a great deal of London during World War II.

In the 1820s the Ice House was used by pioneering ice-merchant and confectioner William Leftwich to store and supply high quality ice to London’s Georgian elites, long before it was possible to manufacture ice artificially. It was extremely fashionable to serve all manner of frozen delights at lavish banquets, and demand was high from catering traders, medical institutions and food retailers. Ice was collected from local canals and lakes in winter and stored, but it was often unclean, and supply was inconsistent.

Leftwich was one of first people to recognise the potential for profit in imported ice: in 1822, following a very mild winter, he chartered a vessel to make the 2000km round trip from Great Yarmouth to Norway to collect 300 tonnes of ice harvested from crystal-clear frozen lakes, an example of “the extraordinary the lengths gone to at this time to serve up luxury fashionable frozen treats and furnish food traders and retailers with ice” (as put by David Sorapure, our Head of Built Heritage). The venture was not without risk: previous imports had been lost at sea, or melted whilst baffled customs officials dithered over how to tax such novel cargo. Luckily, in Leftwich’s case a decision was made in time for the ice to be transported along the Regent’s Canal, and for Leftwich to turn a handsome profit.

The Museum of London Archaeology team unearthed the Ice House in 2015 as part of the redevelopment of Regent’s Crescent, iconic Grade I Listed mews houses originally designed by John Nash, architect to the Prince Regent (later King George IV). The original 1819 structures were destroyed by German bombs during the Blitz and replicas were built in their place in the 1960s. The new development will recreate the originals in exhaustive, period-accurate detail.

The Museum of London Archaeology team unearthed the Ice House in 2015 as part of the redevelopment of Regent’s Crescent, iconic Grade I Listed mews houses originally designed by John Nash, architect to the Prince Regent (later King George IV). The original 1819 structures were destroyed by German bombs during the Blitz and replicas were built in their place in the 1960s. The new development will recreate the originals in exhaustive, period-accurate detail.

The Ice House will play an important role in the redevelopment. It is being restored as the Crescent is being reconstructed. The restored Ice House will be integrated into the Crescent’s gardens. The plan to install a viewing corridor so the remarkable building will be accessible to the public.

The Ice House will play an important role in the redevelopment. It is being restored as the Crescent is being reconstructed. The restored Ice House will be integrated into the Crescent’s gardens. The plan to install a viewing corridor so the remarkable building will be accessible to the public.