If you’ve dreamed of uncovering an untouched coin hoard but never found anything more than a few tin buttons no matter how many fields you’ve scanned, now you can make your dreams come true, as long as they involve paying for it. A full hoard good to go complete with the canvas bag it was stored in is coming up for sale next month at Heritage Auctions all in a single lot.

As individual pieces, the 1883 No CENTS Liberty nickels in this hoard aren’t all that rare or expensive. You can get one for a few bucks, and even uncirculated condition versions can be had for a few hundred. It’s the juicy, dirty history behind that lends them a rakish charm while at the same time keeping their value low.

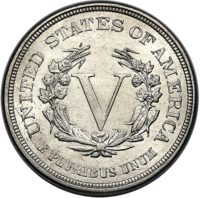

Designed by Chief Engraver Charles E. Barber, who also designed the very similar Liberty Head half-dollar, the 1883 Liberty Head nickel had one feature that made it problematic: the only reference to its denomination was the Roman numeral V inside a laurel wreath on the reverse. But labeling a coin’s value as “five” isn’t exactly specific, especially when there are gold half eagles in circulation with busts of Lady Liberty on the obverse and laurel wreaths on the reverse worth five dollars.

Designed by Chief Engraver Charles E. Barber, who also designed the very similar Liberty Head half-dollar, the 1883 Liberty Head nickel had one feature that made it problematic: the only reference to its denomination was the Roman numeral V inside a laurel wreath on the reverse. But labeling a coin’s value as “five” isn’t exactly specific, especially when there are gold half eagles in circulation with busts of Lady Liberty on the obverse and laurel wreaths on the reverse worth five dollars.

Because of this wee oversight, people of less than honest intention immediately began to collect the nickels as an investment in the counterfeiting possibilities. A little gold-plating, a minor modification to the edges of the nickel so it more closely matched the fiver, a distracted retailer and next thing you know, you walk away from a nickel transaction with $4.95 in change jangling in your pocket. One Josh Tatum was reputed to have been adept at passing off gold-plated nickels as five dollar pieces. His system was foolproof: as a deaf-mute, he would simply present the coin, say nothing, take his change and get out of Dodge. Arrested and tried for fraud, because he never claimed to have paid using a five dollar coin, Tatum was never convicted. Or so the legend goes, anyway. The legend also says the expression “you are joshing me” (meaning “you’re kidding me”) springs from these events, but the idiom predates the 1883 coin by at least decades, so many grains of salt are in order here.

The Mint saw the error of its ways and within months issued an updated coin 1883 Liberty Head nickel with the word “CENTS” on the reverse, leaving a lot of speculators with collections of No CENTS nickels. That’s why they’re not worth all that much on the market today, because they were so widely hoarded by people hoping to get in the passing of fraudulent currency game. The versions with “FIVE CENTS” on the reverse are far rarer and more expensive today because nobody bothered to collect them.

The Mint saw the error of its ways and within months issued an updated coin 1883 Liberty Head nickel with the word “CENTS” on the reverse, leaving a lot of speculators with collections of No CENTS nickels. That’s why they’re not worth all that much on the market today, because they were so widely hoarded by people hoping to get in the passing of fraudulent currency game. The versions with “FIVE CENTS” on the reverse are far rarer and more expensive today because nobody bothered to collect them.

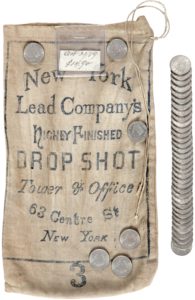

Still, a group of 297 1883 No CENTS Liberty nickels stored in a single bag is not something you see every day. The bag is awesome in and of itself, printed in black text on the front: “New York / Lead Company’s / HIGHLY FINISHED / DROP SHOT / Tower & Office / 63 Centre St / New York / 3”. An attached period label even notes the exact date the coins were stashed in the bag — October 2, 1889 — so more than five years after the issue. They apparently stayed in the bag, untouched, unknown and unpublished, for more than a century until they were acquired by numismatist, US coin expert and rare coin dealer Jeff Garrett in 2009.

Still, a group of 297 1883 No CENTS Liberty nickels stored in a single bag is not something you see every day. The bag is awesome in and of itself, printed in black text on the front: “New York / Lead Company’s / HIGHLY FINISHED / DROP SHOT / Tower & Office / 63 Centre St / New York / 3”. An attached period label even notes the exact date the coins were stashed in the bag — October 2, 1889 — so more than five years after the issue. They apparently stayed in the bag, untouched, unknown and unpublished, for more than a century until they were acquired by numismatist, US coin expert and rare coin dealer Jeff Garrett in 2009.

The nickels will be sold at the U.S. Coins Auction to be held April 25-30 during the Central States Numismatic Society annual convention. Bidding opens online on April 6th.