The stash of 17th century gold coins found during the renovation of a mansion in Plozévet, Brittany, has sold at auction for a collective €1 million ($1.2 million), far exceeding the pre-sale estimate of €250,000-300,000 ($296,000-$355,000).

The stash of 17th century gold coins found during the renovation of a mansion in Plozévet, Brittany, has sold at auction for a collective €1 million ($1.2 million), far exceeding the pre-sale estimate of €250,000-300,000 ($296,000-$355,000).

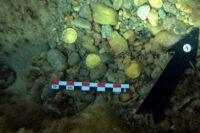

The coins were discovered by stonemasons in 2019. They were in two separate stashes, one set in a metal box in one wall, the other in a bag in another wall. The grand total was 239 coins, all gold, 23 of them minted under Louis XIII, 216 during the reign of Louis XIV. Property owners Véronique and François Mion kept four as souvenirs and put the rest up for auction. There were so many interested buyers at the September 23rd auction and bidding was so intense that it took five hours to get through all the coins.

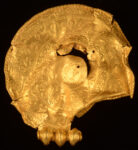

Bidding opened at 8,000 euros for a very rare double Louis d’Or [with a long lock] , depicting Louis XIV and dating back to 1646. It went for 46,000 euros, the same price as a Louis d’Or from Paris dated 1640 and stamped with the Templar’s Cross.

“Bids were flying from everywhere – in the room, on internet and on the telephone,” said auctioneer Florian D’Oysonville.

France passed a treasure law in 2016 that claims all archaeological materials found as property of the state, but it was not retroactive. Because the owners bought the property in 2012, they were able to sell the coins at auction and split the proceeds of the sale 50/50 with the stonemasons who actually found the treasure.

France passed a treasure law in 2016 that claims all archaeological materials found as property of the state, but it was not retroactive. Because the owners bought the property in 2012, they were able to sell the coins at auction and split the proceeds of the sale 50/50 with the stonemasons who actually found the treasure.

Museums do get one other bite at the apple, however. French institutions have the right of preemption, meaning they can claim any lot offered at auction for the final price after the hammer falls. The Monnaie de Paris, France’s national mint which has been in continuous operation since 864 A.D., made liberal use of their statutory rights in the sale of the Plozevet Treasure. They preempted 19 of the 235 coins sold. I’d bet a Louis d’Or that the long lock and templar coins were among them. (Spoiler: I do not have a Louis d’Or.)