Maya blue is an beautiful azure pigment used by the Maya in religious rituals and to decorate rarified pieces. Not only is it super purty, but it’s also remarkably tough. It’s impervious to heat, moisture, even acid and modern solvents. So how did the Maya make such a badass blue?

Maya blue is an beautiful azure pigment used by the Maya in religious rituals and to decorate rarified pieces. Not only is it super purty, but it’s also remarkably tough. It’s impervious to heat, moisture, even acid and modern solvents. So how did the Maya make such a badass blue?

Scientists and archaeologists have known for a while that they combined a white clay mineral called palygorskite with indigo, but they didn’t know exactly how it was made.

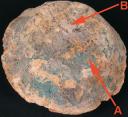

Dr. Dean Arnold of Wheaton College has connected some of the dots by using new technology to examine a bowl that’s been lying around the Field Museum of Chicago for the past 75 years. The bowl contains a hard lump of incense, and Dr. Arnold noticed some palygorskite and indigo seemed to be burned into it.

Dr. Dean Arnold of Wheaton College has connected some of the dots by using new technology to examine a bowl that’s been lying around the Field Museum of Chicago for the past 75 years. The bowl contains a hard lump of incense, and Dr. Arnold noticed some palygorskite and indigo seemed to be burned into it.

Making [Maya blue], he said, requires fusing palygorskite and a small amount of indigo over a slow, low-temperature source of heat, and he began to suspect that, for the ancients, the heat source was burning copal incense. It was a process that could be done in ceramic bowls at religious sacrificial sites like the Sacred Cenote.

To confirm his thinking he enlisted the co-authors of the paper: Jason Branden of Northwestern University’s department of materials science and engineering, and Patrick Ryan Williams, Gary Feinman and J.P. Brown at the Field Museum’s department of anthropology.

They used a scanning electron microscope to study the hardened incense, confirming the presence of palygorskite and indigo.

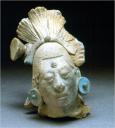

So it seems like the priests were scaring up Maya blue right there on the edge of the Sacred Cenote, painting it on objects (and occasionally people) before throwing them in the pit as a sacrifice.

Tough as it is, the pigment needs time to cure, so the more hastily applied product ended up lining the pit with a 14-foot layer of blue silt.

Tough as it is, the pigment needs time to cure, so the more hastily applied product ended up lining the pit with a 14-foot layer of blue silt.

Edward H. Thompson noticed the lining a hundred years ago when he dredged the cenote for goods and shipped everything he found/stole to Harvard, but he didn’t bother to ask why it was there or what it was.

Dr. Arnold is picking up his slack with fascinating results.