The glaring loophole in the UK’s 1996 Treasure Act that allowed an exceptional Crosby Garrett Roman cavalry helmet to disappear into a private collection will soon be closed. Last year, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport announced a planned revision to the Treasure Act that would update the definition of “treasure” to preserve priceless archaeological patrimony for the public. The ministry has now announced that after a period of consultation and study, the definition of treasure will be changed to allow the designation of objects of great cultural or historical significance as treasure no matter what their material qualities.

The glaring loophole in the UK’s 1996 Treasure Act that allowed an exceptional Crosby Garrett Roman cavalry helmet to disappear into a private collection will soon be closed. Last year, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport announced a planned revision to the Treasure Act that would update the definition of “treasure” to preserve priceless archaeological patrimony for the public. The ministry has now announced that after a period of consultation and study, the definition of treasure will be changed to allow the designation of objects of great cultural or historical significance as treasure no matter what their material qualities.

The 1996 Treasure Act defines treasure as coins in a hoard that are 300 years old or older, two or more prehistoric objects made out of base metal, any non-coin object that is at least 300 years old and composed of at least 10% gold or silver, and gold and silver artifacts less than 300 years old with no known owners or heirs of owners. Any object determined to be treasure according to these criteria is assessed for fair market value and offered to a local museum for that sum. The prize is then split between finder and landowner. If it is does not qualify as treasure, it can be sold to whomever. This definition is a holdover from medieval common law standards that claimed treasure trove — gold and silver objects buried with the intent of later retrieval — for the crown. The Act abolished the ancient expectation of retrieval, but the focus on precious metal content and quantity was a direct descendant of this narrow, outdated view of what constitutes historical treasure.

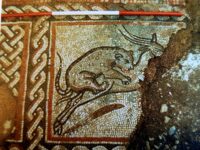

The first year the Treasure Act went into effect, there were 79 treasure cases. Twenty years later in 2017 there were 1,267. There are a lot more metal detector hobbyists today than there were in 1996, and a lot more archaeological treasures have been found, some of which did not meet the criteria for treasure despite their ancient age, rarity, national and international importance. The Crosby Garret helmet and a Roman licking dog statue, both completely unique in the British archaeological record, both dating to the Roman period, both museum quality, failed to meet to the criteria because they were made out of bronze. An Allectus aureus in impeccable condition failed to be declared treasure because it was a single coin instead of one of two or more. They were all sold at auction to the highest bidder.

The first year the Treasure Act went into effect, there were 79 treasure cases. Twenty years later in 2017 there were 1,267. There are a lot more metal detector hobbyists today than there were in 1996, and a lot more archaeological treasures have been found, some of which did not meet the criteria for treasure despite their ancient age, rarity, national and international importance. The Crosby Garret helmet and a Roman licking dog statue, both completely unique in the British archaeological record, both dating to the Roman period, both museum quality, failed to meet to the criteria because they were made out of bronze. An Allectus aureus in impeccable condition failed to be declared treasure because it was a single coin instead of one of two or more. They were all sold at auction to the highest bidder.

The revision was open to public consultation from February until the end of April 2019. The ministry received 1,461 responses to the consultation forms, 1,352 submitted online (one of those was me!). Most of the responses came from individuals, with 190 submitted by organizations or groups. Out of the 190, 51 of them (26.8%) were metal detecting groups, 36 (18.9%) heritage/archaeology groups. The government’s response to the consultation has now been released.

The changes will bring the treasure process into line with other important legislation to protect cultural heritage and collections, including the listing process for historically significant buildings and the export bar system.

A specialist research project running next year will inform the new definition and there will be opportunities for detectorists, archaeologists, museums, academics and curators to contribute to options in development.

As a result of the public consultation, the government will also introduce new measures to improve the experience of the treasure process which include a new time limit to streamline some stages of the process, limiting the number of times the Treasure Valuation Committee can review a case and developing a mechanism to return unclaimed rewards to museums.

The changes will not go into immediate effect. The redefinition will be researched further, the research published, the changes to the code drafted and the attendant legislation passed through Parliament. Implementation of the new policies will, if all goes well, take place in 2022.

The changes will not go into immediate effect. The redefinition will be researched further, the research published, the changes to the code drafted and the attendant legislation passed through Parliament. Implementation of the new policies will, if all goes well, take place in 2022.