Fair warning: this is going to be a long entry.

My man Illusory Tenant introduced me to the Futurists a hundred years and four discussion boards ago. Among his many talents, IT is immensely knowledgeable about music, and Futurism played a raucously innovative role in early 20th century music.

Futurism celebrated the speed, force, and aggressive advancement of technology. Anything traditional, melodic, respectful of the past was anathema. From Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s 1909 Manifesto of Futurism:

Museums, cemeteries! Truly identical in their sinister juxtaposition of bodies that do not know each other. Public dormitories where you sleep side by side for ever with beings you hate or do not know. Reciprocal ferocity of the painters and sculptors who murder each other in the same museum with blows of line and color. To make a visit once a year, as one goes to see the graves of our dead once a year, that we could allow! We can even imagine placing flowers once a year at the feet of the Gioconda! But to take our sadness, our fragile courage and our anxiety to the museum every day, that we cannot admit! Do you want to poison yourselves? Do you want to rot?

(Poor Marinetti would leap out of his grave beat me senseless if he knew he and his movement would be lovingly featured in this obsequiously backward-looking digital cemetery.)

But what inspired this entry is that I just found out that Futurism didn’t limit itself to art and politics. Oh no. Marinetti wrote a cookbook, and what a cookbook it is.

But what inspired this entry is that I just found out that Futurism didn’t limit itself to art and politics. Oh no. Marinetti wrote a cookbook, and what a cookbook it is.

It commands a dramatic combination of flavors, textures and scents, all of them not so much a meal as an experience, to put it mildly. Chemistry is king — eat your derivative hearts out, molecular gastronomists — and the meal itself is performance art as well as nutritional patriotism.

Needless to say, pasta gets the same treatment as museums. From the 1930 Manifesto of Futurist Cooking:

It may be that a diet of cod, roast beef and steamed pudding is beneficial to the English, cold cuts and cheese to the Dutch and sauerkraut, smoked [salt] pork and sausage to the Germans, but pasta is not beneficial to the Italians. For example it is completely hostile to the vivacious spirit and passionate, generous, intuitive soul of the Neapolitans. If these people have been heroic fighters, inspired artists, awe-inspiring orators, shrewd lawyers, tenacious farmers it was in spite of their voluminous daily plate of pasta. When they eat it they develop that typical ironic and sentimental scepticism which can often cut short their enthusiasm.

It’s like looking in a mirror, man.

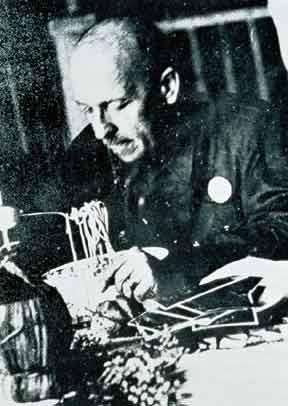

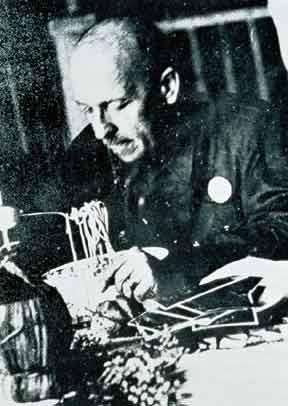

Unfortunately, the following picture of Marinetti made the press right about that time, slightly undercutting the power of his patriotic appeal:

Marinetti claimed in the later Cookbook that this picture was a montage spread by the foes of Futurism to discredit him, the 1930’s equivalent of “That’s not me! My enemies Photoshopped my head on someone else’s naked, prone body!”

The manifesto only listed 4 specific recipes: Alaskan Salmon in the rays of the sun with Mars sauce, Woodcock Mount Rosa with Venus sauce, a sculpted meat cylinder, and the non-meat sculpture Equator + North Pole.

Marinetti was big on the sculpted meat. In fact, the rallying cry of Futurist cookery was “Pasta is dead. Long live sculpted meat!”

In 1931, the manifesto was made (sculpted) flesh in the form of the one and only Futurist restaurant: The Tavern of the Holy Palate in Turin.

In 1931, the manifesto was made (sculpted) flesh in the form of the one and only Futurist restaurant: The Tavern of the Holy Palate in Turin.

Decorated in aluminum, The Holy Palate served Futurist delicacies against a backdrop of poetry readings, perfume sprayed by the waiters over diners and fanned about by an airplane propeller, and in the unkindest cut of all, Wagner operas.

Aerofood: A signature Futurist dish, with a strong tactile element. Pieces of olive, fennel, and kumquat are eaten with the right hand while the left hand caresses various swatches of sandpaper, velvet, and silk. At the same time, the diner is blasted with a giant fan (preferable an airplane propeller) and nimble waiters spray him with the scent of carnation, all to the strains of a Wagner opera.

Chicken Fiat doesn’t have all the accessories, but it’s probably my favorite Futurist abomination. Chicken Fiat (named after the Italian industrial dynamo, natch) is chicken roasted with ball bearings inside until the meat has absorbed the metallic taste, then served on pillows of whipped cream.

But these dishes only scratch the surface of the full multimedia experience that was dinner at The Holy Palate. They enlisted every sense to keep people’s tastebuds in high gear, so to speak.

Smell and taste, unlike sight, hearing, and touch, are chemical senses. As such, they are subject to relatively rapid sensory fatigue. A Futurist cuisine had therefore to find ways of reestablishing “gustatory virginity.” To annul one set of tastes and smells before presenting the next set, a suction fan would draw scents out of the room. To intensify sensory acuity, they

periodically changed the lighting and room temperature, suddenly instructed the diners to quickly move themselves and their dinners two places to the right, released a live turkey into a room where diners had just eaten the bird, and presented blue wine, orange milk, and red mineral water.

Marinetti published The Futurist Cookbook the next year. It elaborated on the principles so concisely stated in the manifesto and included all the recipes from The Holy Palate.

Sadly, it’s long out of print and terribly expensive, so I haven’t had the chance to read it yet. For some reason, it’s not available at my local public library. Damn pasta-eating Communists.

I did find a great description of one recipe in the book that sounds both somewhat palatable and awesome as opposed to just awesome:

Marinetti was not entirely indifferent to the romance of fine dining, and does include a “Nocturnal Love Feast” in his cookbook. The meal, which should be eaten at midnight on the island of Capri, climaxes with a cocktail called the War-in-Bed — a relatively appetizing blend of pineapple juice, egg, cocoa, caviar, red pepper, almond paste, nutmeg, and a whole clove, all mixed in the yellow Strega liqueur. He declares that modern women (preferably sheathed in dresses made of gold graphic patterns) will inevitably be won over by the intellectual rigor of Futurist cooking, describing one beautiful donna’s wide-eyed response: “I’m dazzled! Your genius frightens me!”

The sexy cannot be denied.