Another neat piece of photographic history went on the auction block yesterday in a Bonham’s sale called “India and Beyond – Travel and Photography”. It’s a photo album of pictures taken mainly in Japan in 1898 by the felicitously named Walter J. Clutterbuck.

Besides the awesomeness of his name (somewhat reminscent of eminent Goonies treasure hunter Chester Copperpot), Clutterbuck took what are thought to be the first candid pictures of people on the streets of Meiji-era Japan. Before him, Japanese pictures were posed studio portraits, so not exactly a slice of life.

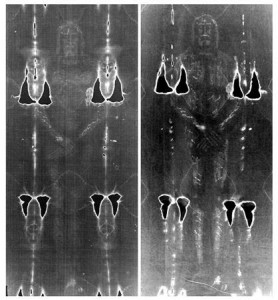

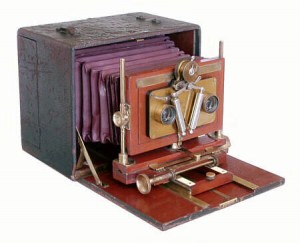

He actually disguised his camera as a pair of binoculars so people didn’t even know he was taking pictures of them. How he managed to disguise a 19th c. stereoscopic camera as binoculars, I do not know. Here’s an example of a Henry Clay stereoscopic model from the 1890s. It’s 5 x 7 or 8 inches in dimension.

I poked around a little and found a style of binoculars from that era that might have served as cover for one of those cameras: the ‘Zodac’ Prismatic Box Binoculars were made by Aitchison & Company in 1895 or so. They’re 8 x 20 inches, and that box design might have been able to contain the entire stereoscopic camera.

I’m just spitballing here. I don’t know the exact model of his camera or how he modified it. I’m terribly curious, though. I wish the binocamera had been included in the sale just so I could see it.

There are a few pictures from his travels to China and Hong Kong in the album as well. The estimate was £3,000 – 4,000, but Bonham’s doesn’t say what it actually sold for, so the album either didn’t sell of the catalog hasn’t been updated after sale.

The latter is unlikely. People bid over the internet these days, so the auction sites update the data in real time.