When famed explorer David Livingstone was stuck in the village of Bambarre, in what is now Congo, in February of 1871, he wrote his old friend Horace Waller on the margins of printed pages with an ink he concocted from local berries. We’re not quite sure how the letters were carried out of Africa since Dr. Livingstone refused to leave the continent and died in 1873, but they may have been carried to England by journalist Henry Stanley who found Livingstone in Bambarre just a few months after the letters were written and who is said to have uttered the immortal but probably apocryphal greeting “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”

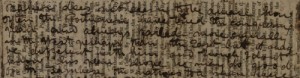

Waller published a book of Livingstone’s diary a year after he died, but it was a highly sanitized volume which depicted Livingstone as the fearless hero. None of Livingstone’s illness and despair made it into the book. These letters present a whole new view into Livingstone’s hardships and depression, but the makeshift ink either faded almost to invisibility or soaked through the page, the paper got brittle, plus the cramped, convoluted script had made them all but illegible until now.

A team of scientists is using a variety of imaging techniques to scan each of the 140 letters and make them legible again.

The imaging technique accentuates the visibility of Livingstone’s ink while simultaneously suppressing the visibility of the underlying print (see picture). It does this by taking 12 separate images of each document, exposing it in turn to 12 different wavelengths of light, from blue ultraviolet, through the visible spectrum to infrared.

By feeding the stack of 12 superimposed images through image analysis software, algorithms pick out and best highlight the Livingstone text. “We get the 12 images that stack up in an image cube, and you can process this digitally,” says Michael Toth, head of the project, who has used the same technique to enhance other valuable ancient documents including the Palimpsest revealing Archimedes’s famous “Eureka” theory, parts of the US Declaration of Independence and Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address condemning slavery.

Different light wavelengths bring out different parts of the text, Toth explains. So Livingstone’s ink disappears under infrared and becomes most distinct under blue.

Here’s a detail of the letter in natural light:

Here’s that same detail after the 12 images are superimposed:

So far only one full letter has been deciphered, but the rest are all queued up for analysis. Right now you can read the full Livingstone letter with fascinating and helpful annotations here. Here’s a paragraph from the first page where after he complains about his friends not writing, he describes his unhappy circumstances:

Ten men here come from Kirk who like the good fellow that he is worked unweariedly to get them & goods off in the midst of disease and death – one gang of porters died quite off and five of my men perished by cholera – We get that from Mecca – letters preceded it thence saying it was coming – We do nothing to stop its hatching in Mecca Medina & Judda which annually become vast cesspools of abomination because the new political economy says let everything alone Formerly it went along shore now it comes inland – In our small camp here we lost 30 & how many Manyema no one knows – All the able bodied all off ivory collecting – if it had continued three instead of two months the camp would have been desolate – Fowls & goats fell first then cattle shivered and died & then men.

There’s a lot more where that came from. Read the whole thing because it’s an awesome buzzkill.

That site also has all kinds of information about the imaging techniques they used, the context of the letter, the letter itself. Eventually all 140 of the letters will be published on Livingstone Online, the primary online source of Livingstone’s writings.