There’s been some debate over who was the first female police officer in the country. Los Angeles boldly proffers its first female police officer hired in 1910, while Portland claims to have gotten the jump on LA by hiring a female officer in 1908. Now Rick Barrett, an amateur historian and former DEA agent, thinks he’s found the real first of the first in Chicago, her far earlier accomplishments obscured when a historian confused her with someone else back in the 20s.

Detective Sergeant Marie Owens was the daughter of Irish famine immigrants. She moved to Chicago from Ottawa with her husband, and when he died of typhoid fever leaving her with 5 children to support, in 1889 she got a job with the city health department as a factory inspector enforcing child labor and compulsory education laws. Not unlike certain federal agencies to this day (*cough* USDA *cough*), the health department had no real power to compel businesses to obey child labor laws. They couldn’t even walk into a factory without a warrant.

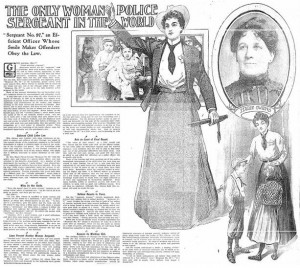

The outcry over Dickensian sweatshop conditions spurred the city to take a firmer hand, and in 1891 Marie Owens was transferred to the police department. She was given powers of arrest, the title of detective sergeant and a police star. It wasn’t just a sinecure or one of those Official Police Assistant certificates they give to kids, either. She was a for real police officer, listed on a record of all police officers from the years 1904 through 1910 found in the archives of the Chicago History Museum. She even made the front page of the Chicago Tribune on August 7, 1904, described in the headline as “the only woman police sergeant in the world.”

The outcry over Dickensian sweatshop conditions spurred the city to take a firmer hand, and in 1891 Marie Owens was transferred to the police department. She was given powers of arrest, the title of detective sergeant and a police star. It wasn’t just a sinecure or one of those Official Police Assistant certificates they give to kids, either. She was a for real police officer, listed on a record of all police officers from the years 1904 through 1910 found in the archives of the Chicago History Museum. She even made the front page of the Chicago Tribune on August 7, 1904, described in the headline as “the only woman police sergeant in the world.”

Owens described how she had discovered children — “frail little things” as young as 7 years old — working in factories all over the city. Some assembly lines were staffed by scores of kids, many looking suspiciously younger than 14, the age at which children were legally allowed to work.

“In my sixteen years of experience I have come across more suffering than ever is seen by any man detective,” she said.

Her work affected thousands of children. She established schools within department stores so young workers could get an education, and she persuaded other employers to shorten their workdays, according to historical news accounts.

In 1923, she retired after 32 years with the department. Four years later, she died at age 74. The brief, eight-line death notice that ran in local papers didn’t mention her police career. Already, her work seemed to be fading from memory. And when a historian confused her with another woman and described Owens in a book about policewomen as a patrolman’s widow, her accomplishments were struck from history.

In 2007, Rick Barrett found a reference to her as the wife of a fallen policeman when he was researching Chicago police officers. When he looked up the death records, however, he found a discrepancy. Owens’ husband was listed as a gas fitter, not a cop. His interest now fully piqued, Barrett combed through all the records he could find, piecing together her remarkable life story and now finally calling attention to this overlooked pioneer.