It’s the 84th anniversary of Harry Houdini’s death today, since he so thoughtfully got himself punched in the inflamed appendix and held out just long enough for peritonitis to kill him on the spookiest day of the year. Just in time to celebrate his dramatic life and death, a new exhibit at The Jewish Museum in New York has put the artistry, craftsmanship and showmanship of Harry Houdini on display for the first time in a major art museum.

It’s the 84th anniversary of Harry Houdini’s death today, since he so thoughtfully got himself punched in the inflamed appendix and held out just long enough for peritonitis to kill him on the spookiest day of the year. Just in time to celebrate his dramatic life and death, a new exhibit at The Jewish Museum in New York has put the artistry, craftsmanship and showmanship of Harry Houdini on display for the first time in a major art museum.

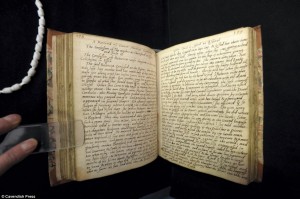

Houdini: Art and Magic doesn’t reveal any magicians’ secrets. It tells the story of Ehrich Weiss, a Hungarian immigrant who ran away from his Wisconsin home when he was 12 to join the circus. He came back, though, to help support the family, and only began his vaudeville career in earnest after his father died in 1892 when Harry was 18. He started off doing card tricks. He quickly moved on to handcuff escapes and by 1900 he was a sensation touring Europe as “The Handcuff King.”

The exhibit recreates the shadowy interiors and sharp spotlights of the vaudeville halls that launched Houdini’s magic career. There are photographs, posters, rare film footage of his dramatic public escapes as well as films starring him shot by his own production company in the late teens/early twenties, and coolest of all, some of his most famous props.

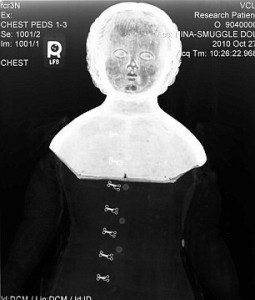

Far more intriguing are Houdini’s own main props: a weighty steamer trunk, an oversize milk can and a vertical, coffinlike box with a glass front. These were the sites of his most famous acts: the trunk and can were everyday objects, the exhibition notes, well within the ken of immigrant audiences.

The trunk here, we learn, was one with which Houdini performed the “Metamorphosis” trick. He would be tied up, put in handcuffs, perhaps, then stuffed inside a tightly tied sack and locked in the trunk. His assistant would stand on top. A curtain would then shield them from view. And in three seconds, it would drop, revealing not the assistant but Houdini himself standing atop the trunk, his assistant locked and bound inside.

This wasn’t a trick of Houdini’s invention, but he expanded its resonance. It seemed to demonstrate the power to overcome bondage, to dissolve material obstacles, to confound expectations. But Houdini took his act further. Being locked in a trunk is nobody’s idea of a good time, but this was still playful artifice. What if he were stuffed inside a milk can, and it was then filled with water? The trick starts to invoke claustrophobic terror. (Houdini owned one of Edgar Allan Poe’s desks.)

And if the milk can were replaced with a vertical glass-walled, water-filled, coffinlike box, as it was in 1912, the audience members wouldn’t even have to imagine that terror. They watch Houdini being lowered upside down into his “water torture cell” and see him pressed against the glass as he is locked in place. Two assistants stand with axes, prepared to smash the apparatus if Houdini doesn’t make it out in time. When he does (we don’t see how), it seems a conquest of morbid fear, a defiance of death.

You can’t see inside any of the props, though. That would be telling. The Water Torture Cell on display is the only reproduction. The rest are Harry’s own devices. You have to listen closely to understand through the noise, but here’s a recording of Harry Houdini describing his Water Torture Cell procedure for a 1914 audience:

The exhibit is not just neat gadgets. It also features contemporary art inspired by Houdini, like a pair of chained holographic hands emerging from the milk can. It ties all of that together with the art and craftsmanship of Harry’s showstopping performances and with the sociological significance of his Jewish immigrant heritage.

The exhibit runs in New York until March 27, 2011. Then it will travel to Los Angeles, San Francisco and Madison, Wisconsin.