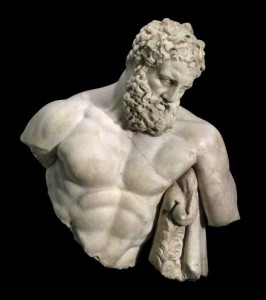

In a reversal of a decades-long position, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts has agreed to return the torso and head of a 2nd century A.D. statue of Herakles to Turkey so that it may be reunited with its hips and legs in the Antalya Museum. The statue, a Roman copy of a 4th century B.C. bronze by the Greek master Lysippos of Sikyon, depicts the aged hero tiredly leaning on his club draped with the skin of the Nemean lion. The bottom half was unearthed in 1980 during an excavation in Perge (the ancient Greek city of Perga) on the southwestern Mediterranean coast of Turkey. The top half appeared seemingly out of nowhere on the US market in 1981.

In a reversal of a decades-long position, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts has agreed to return the torso and head of a 2nd century A.D. statue of Herakles to Turkey so that it may be reunited with its hips and legs in the Antalya Museum. The statue, a Roman copy of a 4th century B.C. bronze by the Greek master Lysippos of Sikyon, depicts the aged hero tiredly leaning on his club draped with the skin of the Nemean lion. The bottom half was unearthed in 1980 during an excavation in Perge (the ancient Greek city of Perga) on the southwestern Mediterranean coast of Turkey. The top half appeared seemingly out of nowhere on the US market in 1981.

The MFA bought the piece from Mohammad Yeganeh, a German antiquities dealer who claimed that it was his mother’s and that she had bought it in Germany in 1950. Despite the fact that the legs had been found the year before and that there wasn’t a whisper of documentation for this ridiculous “my mom ate my homework” excuse, the MFA and New York collectors Leon Levy and Shelby White would split the cost and purchase the statue (with the museum’s half coming from a Shelby foundation grant), with the stipulation that Levy’s 50% ownership stake would go to the museum after his death.

It wasn’t until 1990 when the MFA loaned the top half for an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that the remarkable coincidence of how well the torso matched the legs in Turkey made the news. Cornelius C. Vermeule III, the MFA’s curator of classical art, dismissed the connection between the two parts. “Weary Herakles” was a popular subject — there are at least a hundred later copies of Lysippos’ original in museums and collections — so the top and bottom could belong to any number of iterations.

It wasn’t until 1990 when the MFA loaned the top half for an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that the remarkable coincidence of how well the torso matched the legs in Turkey made the news. Cornelius C. Vermeule III, the MFA’s curator of classical art, dismissed the connection between the two parts. “Weary Herakles” was a popular subject — there are at least a hundred later copies of Lysippos’ original in museums and collections — so the top and bottom could belong to any number of iterations.

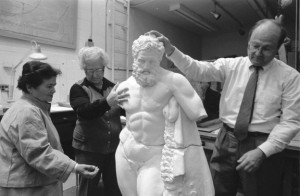

He was so insistent that they were from different statues that Vermeule proposed the two museums take plaster casts of the parts and see if they fit together. In 1992 the casts were brought together and they did fit. Perfectly. After that, the MFA changed its argument. Now they were keeping the top half because it could have been excavated “any time since the Italian Renaissance” instead of after 1906, the year Turkish law established state ownership of archaeological finds thus making export of ancient artifacts illegal. Their official position was that they had acquired the statue legally and that Turkey couldn’t prove otherwise.

Turkey continued to ask for restitution. The display of the legs in the Antalya Museum included a collage of newspaper stories about the controversy and placed a picture of the MFA’s top half above the bottom half, but even after Leon Levy died in 2003, making the museum the sole owner of the statue, another four years would pass before MFA deputy director Katherine Getchell would initiate talks with Turkey.

Turkey continued to ask for restitution. The display of the legs in the Antalya Museum included a collage of newspaper stories about the controversy and placed a picture of the MFA’s top half above the bottom half, but even after Leon Levy died in 2003, making the museum the sole owner of the statue, another four years would pass before MFA deputy director Katherine Getchell would initiate talks with Turkey.

During these meetings the Turkish representatives provided evidence that the Perge site had been looted during the initial excavation. That evidence is the official reason the Museum of Fine Arts has agreed to return Herakles’ chest and head to Turkey.

Osman Murat Suslu, Turkey’s general director of museums and cultural heritage, said that he’s thrilled that after so many years, the “Weary Herakles” is coming home. He is even willing to give the MFA a short-term loan of the unified piece for an exhibition. Getchell had requested that during negotiations.

The MFA can’t predict when the reunited statue might go on display, but Getchell said that the MFA hoped the unified piece would be seen first in Boston. If Turkey agrees to lend the bottom half to the MFA, it would take several months for the piece to be put together and conserved. That would leave the MFA with a rough target of 2012 for unveiling the two halves, Getchell said. Ultimately, the unified piece would return to Turkey.