In 1504, the Gonfalionere of Justice, leader of the Florentine Republic, Piero Soderini commissioned Leonardo da Vinci to decorate a wall in the newly built Hall of Five Hundred, the room where Florence’s Great Council met in the Palazzo Vecchio.

According to Giorgio Vasari’s biography of Leonardo in the Lives of the Artists, the people of Florence clamored for a memento of the great artist’s presence among them. They decided on a large-scale mural depicting the 1440 Battle of Anghiari in which greatly outnumbered Florentine armies held a bridge against the Duke of Milan’s mercenaries, thereby keeping central Italy’s free from Milanese control.

Vasari glowingly describes Leonardo’s design:

Whereupon Leonardo, determining to execute this work, began a cartoon in the Sala del Papa, an apartment in S. Maria Novella, representing the story of Niccolò Piccinino, Captain of Duke Filippo of Milan; wherein he designed a group of horsemen who were fighting for a standard, a work that was held to be very excellent and of great mastery, by reason of the marvellous ideas that he had in composing that battle; seeing that in it rage, fury, and revenge are perceived as much in the men as in the horses, among which two with the forelegs interlocked are fighting no less fiercely with their teeth than those who are riding them do in fighting for that standard, which has been grasped by a soldier, who seeks by the strength of his shoulders, as he spurs his horse to flight, having turned his body backwards and seized the staff of the standard, to wrest it by force from the hands of four others, of whom two are defending it, each with one hand, and, raising their swords in the other, are trying to sever the staff; while an old soldier in a red cap, crying out, grips the staff with one hand, and, raising a scimitar with the other, furiously aims a blow in order to cut off both the hands of those who, gnashing their teeth in the struggle, are striving in attitudes of the utmost fierceness to defend their banner; besides which, on the ground, between the legs of the horses, there are two figures in foreshortening that are fighting together, and the one on the ground has over him a soldier who has raised his arm as high as possible, that thus with greater force he may plunge a dagger into his throat, in order to end his life; while the other, struggling with his legs and arms, is doing what he can to escape death.

It is not possible to describe the invention that Leonardo showed in the garments of the soldiers, all varied by him in different ways, and likewise in the helmet crests and other ornaments; not to mention the incredible mastery that he displayed in the forms and lineaments of the horses, which Leonardo, with their fiery spirit, muscles, and shapely beauty, drew better than any other master.

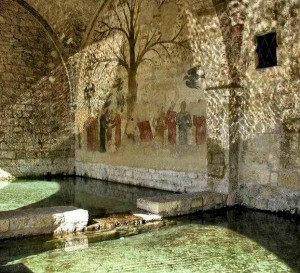

In classic Leonardo style, he invented an accordion-folding scaffold to reach the top of his immense canvas. Also in a classic but less fortunate Leonardo style, he invented a new undercoat to apply to the wall under his oil painting. He didn’t want to use fresco because it had failed rather spectacularly in The Last Supper, so he scared up some weird mixture that in tests worked quite well. On the huge scale of the wall, though, where it was virtually impossibly to keep the environment evenly warm, the primer didn’t dry quickly enough and before his very eyes the paint started dripping. Leonardo brought in braziers to heat the wall and try to preserve what he could, but only the bottom of the painting managed to dry on time. The paints on the top were hopelessly intermingled. Bummed, Leonardo abandoned the project.

Even incomplete, the mural was widely revered. Many copies were made of it over the years, most notably by Peter Paul Rubens in 1603, based on a 1553 engraving by Lorenzo Zacchia. By the time Rubens made his version, Leonardo’s original was long gone. The Hall of the Five Hundred was enlarged between 1555 and 1572, and in the process The Battle of Anghieri and the incomplete work by Michelangelo that was across from it were both lost.

Even incomplete, the mural was widely revered. Many copies were made of it over the years, most notably by Peter Paul Rubens in 1603, based on a 1553 engraving by Lorenzo Zacchia. By the time Rubens made his version, Leonardo’s original was long gone. The Hall of the Five Hundred was enlarged between 1555 and 1572, and in the process The Battle of Anghieri and the incomplete work by Michelangelo that was across from it were both lost.

It was none other than Giorgio Vasari who was in charge of the restructuring of the hall. He and his associates painted vast battle murals on the walls, including over the wall that had once held Leonardo’s lost masterpiece. On one of those murals, way up high, Vasari left a curious note. There’s no lettering anywhere else on this intricate scene of army against army, but in one green standard Vasari painted two words: “Cerca Trova,” seek and find.

It was none other than Giorgio Vasari who was in charge of the restructuring of the hall. He and his associates painted vast battle murals on the walls, including over the wall that had once held Leonardo’s lost masterpiece. On one of those murals, way up high, Vasari left a curious note. There’s no lettering anywhere else on this intricate scene of army against army, but in one green standard Vasari painted two words: “Cerca Trova,” seek and find.

Florentine art historian and University of California, San Diego, professor Maurizio Seracini found Vasari’s note in the 1970s. Ever since then, he’s tried to find out more about the wall and might be behind it. Ultrasounds taken in 1976 detected no painting behind the current one. In 2000, Seracini used radar scanning to discover that Vasari had painted his work on a new brick wall, not directly on Leonardo’s surface. Could Vasari, who we know held Anghiari in the highest of esteem, had built a brick surface to keep Leonardo’s work, whatever was left of it, intact? Is that what seekers would find if they looked?

Florentine art historian and University of California, San Diego, professor Maurizio Seracini found Vasari’s note in the 1970s. Ever since then, he’s tried to find out more about the wall and might be behind it. Ultrasounds taken in 1976 detected no painting behind the current one. In 2000, Seracini used radar scanning to discover that Vasari had painted his work on a new brick wall, not directly on Leonardo’s surface. Could Vasari, who we know held Anghiari in the highest of esteem, had built a brick surface to keep Leonardo’s work, whatever was left of it, intact? Is that what seekers would find if they looked?

The problem is how do we find out what, if anything, is behind the bricks without dismantling the 16th century works. Enter freelance photographer Dave Yoder. In 2007, Yoder was assigned by National Geographic to do a story about Seracini’s decades-long investigation, and in 2010, National Geographic inked a deal with Florence to pay the city $250,000 for exclusive rights to publish the results of Mr. Seracini’s research.

It was Yoder who found a possible solution to the conundrum. Googling, he found nuclear physicist Robert Smither who was creating a gamma ray camera that would be able to take high-resolution pictures of cancer inside of a patient without invasive exploration.

Mr. Smither figured that his camera, which essentially uses copper crystals in place of lens glass to focus the gamma rays that bounce back when an object is sprayed with neutrons, could provide a definitive answer. It could not only determine whether the Leonardo painting was there by identifying the chemicals in the paint but could also capture an image of the hidden work — without damaging the Vasari fresco on top.

Thus ensued an unlikely and somewhat surreal turn of events in which Mr. Yoder, between glossy-magazine assignments, found himself borrowing time at a facility of Italy’s energy research agency in Frascati, outside Rome. The testing, in June 2010, went well. The team took pigments similar to those used by Leonardo and original bricks from Leonardo’s era that Mr. Seracini found at the Palazzo Vecchio and sprayed them with neutrons. The gamma rays that bounced back were strong enough for Mr. Smither to collect and read.

That convinced Mr. Smither that if they exposed the wall in the Hall of Five Hundred to neutrons, they could tell from the gamma rays that bounced back whether Leonardo’s painting was still there. And, at that point, they could build a special camera that would create an image from those particular gamma rays.

It’s the best of both worlds: we get to see what’s left of Leonardo’s painting without damaging the wall on top of it. The only problem is money. In order to develop and test the gamma camera, the researchers need $265,000. Since everyone is broke, they’ve taken it to Kickstarter where people can donate a dollar or a hundred thousand of them to see this plan come to fruition.

I think Leonardo, compulsive inventor that he was, would be absolutely thrilled to have a new gamma ray camera built so that we can see his art.