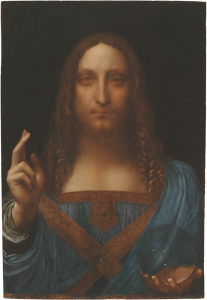

There are a grand total of 14 oil paintings in the world known to have been painted by Leonardo da Vinci, or rather there were 14. Now there are 15 because a Leonardo that was lost centuries ago has been authenticated by experts from the US and UK. The painting depicts Christ as the Salvator Mundi, the Savior of the World, facing forwards with two fingers of his right hand raised in blessing and a crystal globe in his left hand. It’s oil on a walnut panel and is 2 x 1.5 feet (26 x 18 inches, 66 x 45 cm) in size.

There are a grand total of 14 oil paintings in the world known to have been painted by Leonardo da Vinci, or rather there were 14. Now there are 15 because a Leonardo that was lost centuries ago has been authenticated by experts from the US and UK. The painting depicts Christ as the Salvator Mundi, the Savior of the World, facing forwards with two fingers of his right hand raised in blessing and a crystal globe in his left hand. It’s oil on a walnut panel and is 2 x 1.5 feet (26 x 18 inches, 66 x 45 cm) in size.

The Salvator Mundi was a well-known painting when Leonardo first made it around 1500. That’s why we still know of it despite its having dropped out of circulation for hundreds of years, because there are multiple copies made by his students and other artists in his style. Several of these copies have been put forth as the lost original, but scholars disagreed and none of them was widely accepted. There are also two preparatory drawings by Leonardo in the Royal Library at Windsor which show the drapery of Christ’s robe and raised arm just as seen in the painting.

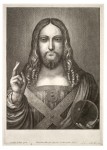

Our best historical reference is a detailed etching made in 1650 by Wenceslaus Hollar, who was commissioned to make the copy by Henrietta Maria, Queen of England, widow of the freshly decapitated English King Charles I. Hollar captioned the etching “Leonardus da Vinci pinxit. Wenceslaus Hollar fecit Aqua forti, secundum originale. Ao 1650.” (Translation: “Leonardo da Vinci painted it. Wenceslaus Hollar made it out of strong water [ie, nitric acid used for the etching], according to the original. Year 1650.”) There’s a record of the painting in Charles I’s collection in 1649, so it seems Hollar made his drawing from Leonardo’s completed original.

Our best historical reference is a detailed etching made in 1650 by Wenceslaus Hollar, who was commissioned to make the copy by Henrietta Maria, Queen of England, widow of the freshly decapitated English King Charles I. Hollar captioned the etching “Leonardus da Vinci pinxit. Wenceslaus Hollar fecit Aqua forti, secundum originale. Ao 1650.” (Translation: “Leonardo da Vinci painted it. Wenceslaus Hollar made it out of strong water [ie, nitric acid used for the etching], according to the original. Year 1650.”) There’s a record of the painting in Charles I’s collection in 1649, so it seems Hollar made his drawing from Leonardo’s completed original.

It was sold after the King’s execution but returned to the crown when he son, Charles II, was restored to the monarchy in 1660. From there it went into the Duke of Buckingham’s collection and then dropped out of sight after his son sold it in 1763. The painting cropped up again in 1900 but was very much the worse for wear. It had been overpainted, varnished, poorly restored and damaged past the point of recognition. You can see the repainting in the black and white picture (right) taken after 1900 but before 1912.

It was sold after the King’s execution but returned to the crown when he son, Charles II, was restored to the monarchy in 1660. From there it went into the Duke of Buckingham’s collection and then dropped out of sight after his son sold it in 1763. The painting cropped up again in 1900 but was very much the worse for wear. It had been overpainted, varnished, poorly restored and damaged past the point of recognition. You can see the repainting in the black and white picture (right) taken after 1900 but before 1912.

When British collector Sir Frederick Cook purchased it that year, he didn’t know it was a Leonardo. It was exhibited as a “Milanese School” painting from ca. 1500 when Sir Frederick put his collection of old masters on display in the 40s. It was attributed to Leonardo’s talented student Boltraffio when the trustees of the Cook collection put the painting up for auction at Sotheby’s London in 1958 after Sir Frederick’s death. It earned them 45 shiny pounds. (You know they are collectively beating themselves in the face right about now.)

Salvator Mundi was in an American private collection from that point until 2005, when it was purchased from what appears to be a consortium of art dealers, but the owners are keeping fairly mum about it. They commissioned New York art historian and dealer Robert Simon to study the piece and he saw through the repaint, dirt, varnish and tragic cleanings past to the details of Leonardo-level quality like the pattern of the stole and the bubbles in the crystal orb.

They still didn’t think it was an actual Leonardo original at that point. It was only after years of cleaning and restoration that the full beauty of the painting gradually revealed itself. In the fall of 2007, they called in the big Leonardo guns.

At that time, the painting was viewed by Mina Gregori (University of Florence) and Nicholas Penny (Director, National Gallery, London; then Curator of Sculpture, National Gallery of Art, Washington). In 2008, the painting was studied at The Metropolitan Museum of Art by museum curators Carmen Bambach, Andrea Bayer, Keith Christiansen, and Everett Fahy, and by Michael Gallagher, head of the Department of Paintings Conservation. In late May 2008, the painting was taken to the National Gallery in London, where it could be directly compared with Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks of approximately the same date. Several specialist Leonardo scholars were also invited to study the two paintings together. These included Carmen Bambach, David Alan Brown (Curator of Italian Painting, National Gallery of Art, Washington), Maria Teresa Fiorio (Raccolta Vinciana, Milan), Martin Kemp (University of Oxford), Pietro C. Marani (Professor of Art History at the Politecnico di Milano), and the gallery’s Curator of Italian paintings Luke Syson. More recently, following the completion of conservation treatment in 2010, the painting has again been studied in New York by several of the above, as well as by David Ekserdjian (University of Leicester).

The study and examination of the painting by these scholars resulted in an unequivocal consensus that the Salvator Mundi was painted by Leonardo da Vinci, and that it is the single original painting from which the many copies and versions depend. Individual opinions vary slightly in the matter of dating. Most place the painting at the end of Leonardo’s Milanese period in the late 1490s, contemporary with the completion of the Last Supper. Others believe it to be slightly later, painted in Florence (where Leonardo moved in 1500), contemporary with the Mona Lisa.

The experts were convinced this was the real Salvator Mundi because of its stylistic adherence to Leonardo’s known work, the high quality execution, its matching the Windsor preparatory drawings and Hollar’s etching, how much better it is than the 20 known copies, plus the discovery of pentimenti, first ideas for the work that were painted over but not seen in the etching or in the copies. The science — chemical analysis of the paint, colors and wood — confirms that the materials are consistent with those used in other works known to be Leonardo’s.

They were so decisively persuaded, in fact, that Salvator Mundi will be shown for the first time at London’s National Gallery Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan show, an unprecedented exhibition of work from Leonardo’s years at the court of Ludovico Sforza, ruler of Milan. Seven of the now 15 known Leonardo paintings will be on display in this show. To say that is unprecedented is an understatement. That’s half of all the remaining Leonardos in one place, one of them the first new Leonardo painting found since 1909, when the Benois Madonna was discovered.