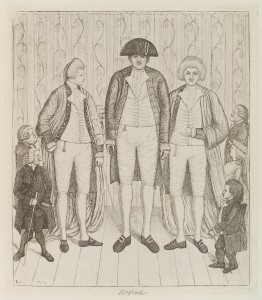

Charles Byrne was an 18th century Irishman of extraordinary stature who became famous as “the Irish Giant” in London’s Cox’s Museum (a sideshow/museum of oddities similar to P.T. Barnum’s American Museum in New York City). Born in 1761, Byrne was already abnormally tall in childhood, and by the time he was a teenager his height had made him a popular local sideshow attraction. When he was 21, he left Ireland to seek fame and fortune in London. His 7’7″ height garnered him the giant gig at Cox’s Museum and he was instantly a huge hit. Unfortunately it was a short-lived success. Under the strain of his deteriorating health and the pressures of celebrity, barely more than a year after his move to London, the Irish Giant drank himself to death.

Charles Byrne was an 18th century Irishman of extraordinary stature who became famous as “the Irish Giant” in London’s Cox’s Museum (a sideshow/museum of oddities similar to P.T. Barnum’s American Museum in New York City). Born in 1761, Byrne was already abnormally tall in childhood, and by the time he was a teenager his height had made him a popular local sideshow attraction. When he was 21, he left Ireland to seek fame and fortune in London. His 7’7″ height garnered him the giant gig at Cox’s Museum and he was instantly a huge hit. Unfortunately it was a short-lived success. Under the strain of his deteriorating health and the pressures of celebrity, barely more than a year after his move to London, the Irish Giant drank himself to death.

After a lifetime spent on display, Byrne’s deepest fear was that his body would be stolen by “resurrection men” in the employ of eminent Scottish anatomist John Hunter who was famous for his collection of anatomical specimens and oddities. Byrne told his friends that when he died he wanted to be sealed in a lead coffin and buried at sea to avoid this horror. One of those friends turned coat in the most despicable way: he became the resurrection man Byrne feared. Hunter paid him 500 pounds (almost $80,000 in today’s money) to steal the body when the burial party stopped overnight on their way to the English Channel. He put heavy stones in the casket and gave Hunter his friend’s body.

Hunter boiled it immediately, probably in fear of imminent discovery, and hid the skeleton for four years. Once he figured the coast was clear, he put the giant’s skeleton on display in his museum. After Hunter’s death, his collection was bought by the British government and became the core of the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in London which to this day has Charles Byrne’s body on display.

Hunter boiled it immediately, probably in fear of imminent discovery, and hid the skeleton for four years. Once he figured the coast was clear, he put the giant’s skeleton on display in his museum. After Hunter’s death, his collection was bought by the British government and became the core of the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in London which to this day has Charles Byrne’s body on display.

Professor of medical ethics Len Doyal and lawyer Thomas Muinzer argue in the latest issue of the British Medical Journal that it’s high time Charles’ wishes were respected and his remains buried at sea.

The fact is that Hunter knew of Byrne’s terror of him and ignored his wishes for the disposal of his body. What has been done cannot be undone but it can be morally rectified. Surely it is time to respect the memory and reputation of Byrne: the narrative of his life, including the circumstances surrounding his death.

The Hunterian Museum and the Royal College of Surgeons’ possession of Byrne’s skeleton may have led to beneficial medical outcomes. However, as a justification for not burying his skeleton, that case is no longer tenable. Past research on Byrne did not require the display of his skeleton; merely medical access to it. Moreover, now that Byrne’s DNA has been extracted, it can be used in further research. Equally, it is likely that if given the opportunity to make an informed choice, living people with acromegaly will leave their bodies to research or participate in it while alive, or both. Finally, for the purposes of public education, a synthetic archetypical model of an acromegalic skeleton could be made and displayed. Indeed, such skeletons are now used in medical education throughout the world.

The Royal College of Surgeons disagrees. Their position is that the skeleton is still a unique source of important medical research.

Dr. Sam Alberti, director of the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons, said: “The Royal College of Surgeons believes that the value of Charles Byrne’s remains, to living and future communities, currently outweighs the benefits of carrying out Byrne’s apparent request to dispose of his remains at sea.

“A vivid example of the value of having access to the skeleton is the current research into Familial Isolated Pituitary Adenoma (FIPA).

“This genetically links Byrne to living communities, including individuals who have requested that the skeleton should remain on display in the museum.

“At the present time, the museum’s Trustees consider that the educational and research benefits merit retaining the remains.”

I can’t say I find the utilitarian argument tremendously persuasive. It seems to me Charles Byrne has given far more than his fair share of himself to science already. Time for what’s left of him to rest in peace and, for the first time, in privacy.