The most ambitious digitization project I’ve ever heard of is halfway to its goal of putting every single publicly owned oil painting (plus tempera and acrylic) in the United Kingdom online. A joint effort of the Public Catalogue Foundation and the BBC, Your Paintings now has 104,000 artworks by the likes of Degas and Rubens uploaded to the website out of an estimated 200,000. It’s the first national online art museum ever attempted. Just to give you a sense of the scale, there are only 3,000 paintings in the immense National Gallery.

The most ambitious digitization project I’ve ever heard of is halfway to its goal of putting every single publicly owned oil painting (plus tempera and acrylic) in the United Kingdom online. A joint effort of the Public Catalogue Foundation and the BBC, Your Paintings now has 104,000 artworks by the likes of Degas and Rubens uploaded to the website out of an estimated 200,000. It’s the first national online art museum ever attempted. Just to give you a sense of the scale, there are only 3,000 paintings in the immense National Gallery.

You’d have to visit over 3,000 art galleries, museums, libraries, etc. to see the Your Paintings collection in person, and even that wouldn’t be enough. Some of the paintings are in private institutions like Bishop’s palaces and Oxford and Cambridge (they were deemed important national patrimony despite their technical private ownership) and aren’t on display. Even the ones in public museums are often in storage or being conserved. An estimated 80% of the 200,000 oil paintings in the national collection are not available for public viewing at any given time. Besides, even if you could access all of the paintings, it’s unlikely you’d get well-known actors and artists to take you on a guided tour of their favorite pieces and themes.

You can already search the website by artist, collection, location and thanks to the 5,000 members of the public (plus curators and experts) who have signed up to tag each painting with relevant subjects, soon you’ll be able to search the entire database by keyword as well. There are over a million tags already in the system. If you’d like to be a tagger too, sign up here.

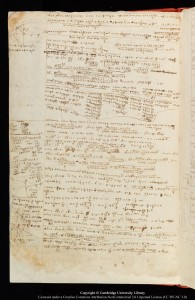

If your interests lie more on the history of science spectrum, Cambridge University Library has digitized and uploaded 4,000 pages of works by Sir Isaac Newton, including a fully annotated copy of the Principia Mathematica, drafts of his book on optics, his college notebooks and the “Waste Book,” a large volume filled with Newton’s notes and calculations, including some important work in the development of calculus, that he used when he had to leave Cambridge during the Great Plague of 1664.

Each page has been scanned individually in high resolution. You can zoom in on the smallest detail, or you can zoom out and read the transcription of the sometimes challenging handwriting. (Not all pages have transcriptions.) You can also download images of every page.

Each page has been scanned individually in high resolution. You can zoom in on the smallest detail, or you can zoom out and read the transcription of the sometimes challenging handwriting. (Not all pages have transcriptions.) You can also download images of every page.

The Cambridge Digital Library, in collaboration with the Newton Project at the University of Sussex, has been digitizing their Newton manuscripts since June 2010. They had to take their time with it because many of the works were in need of conservation before they could be scanned. These 4000 pages are just the beginning. Thousands more pages will be uploaded in the coming year. The ultimate goal is to have Cambridge’s full Newton collection online.

Once that’s done, they’ll move on to digitize their collection of works by Charles Darwin and the archive of the Board of Longitude.