It’s the day before the Kalends of September and you know what that means: it’s the birthday of Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, aka the emperor Caligula. This one is a special birthday even under a numerical system without a zero because if Caligula really had been the immortal deity he hallucinated himself to be, he’d have turned MM years old today.

It’s the day before the Kalends of September and you know what that means: it’s the birthday of Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, aka the emperor Caligula. This one is a special birthday even under a numerical system without a zero because if Caligula really had been the immortal deity he hallucinated himself to be, he’d have turned MM years old today.

Gaius was born in Anzio to military hero Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus and Vipsania Agrippina, Caesar Augustus’ grand-daughter. Gaius was just two years old when the family moved with Germanicus when he was appointed commander of the army in Germany. His father dressed little Gaius in a miniature army outfit, including child-sized versions of caligae, the hobnailed sandal boots worn by common soldiers. That’s how he got his nickname, Caligula, meaning little caliga. He became a much-beloved mascot. Suetonius says the army loved him so much that his mere presence stopped a mutiny after the death of Augustus.

When he was around six years old, Little Boot and his family were dispatched to Asia where Germanicus made Roman provinces out of Cappadocia and Commagene and was poisoned in Antioch probably by Piso, the governor of Syria. Emperor Tiberius was thought to have ordered the murder of his nephew and adoptive son. Gaius lived with his mother until Tiberius had her exiled in 29 A.D., then he moved in with his redoubtable grandmother Livia. She died that same year, so he moved in with his other grandmother Antonia, daughter of Augustus’ sister Octavia and Mark Anthony.

When he was around six years old, Little Boot and his family were dispatched to Asia where Germanicus made Roman provinces out of Cappadocia and Commagene and was poisoned in Antioch probably by Piso, the governor of Syria. Emperor Tiberius was thought to have ordered the murder of his nephew and adoptive son. Gaius lived with his mother until Tiberius had her exiled in 29 A.D., then he moved in with his redoubtable grandmother Livia. She died that same year, so he moved in with his other grandmother Antonia, daughter of Augustus’ sister Octavia and Mark Anthony.

By 31 A.D., Tiberius had exiled/killed everyone in his family except for himself and his sisters. They were theoretically free, but in reality under constant guard and in constant danger of falling afoul of the emperor and suffering the same fate as their brothers, mother and father. Tiberius brought Caligula to live with him in his villa of debauchery in Capri, and Little Boot made himself an able collaborator. His ability to ingratiate himself with the emperor saved his life, although it may have severely twisted his morals at the same time. Suetonius seems to think he was a bad seed all along.

Yet even at that time he could not control his natural cruelty and viciousness, but he was a most eager witness of the tortures and executions of those who suffered punishment, revelling at night in gluttony and adultery, disguised in a wig and a long robe, passionately devoted besides to the theatrical arts of dancing and singing, in which Tiberius very willingly indulged him, in the hope that through these his savage nature might be softened. This last was so clearly evident to the shrewd old man, that he used to say now and then that to allow Gaius to live would prove the ruin of himself and of all men, and that he was rearing a viper for the Roman people and a Phaethon for the world.

(Phaeton was the son of the sun god Helios and Clymene who asked to be allowed to drive his father’s chariot for a day to prove his paternity. He was horrible at it, alternately freezing and burning the earth so badly that he turned half of Africa into a desert. Zeus had to kill him with a thunderbolt to prevent him from burning the globe to a cinder.)

When Tiberius died in 37 A.D., Caligula took the throne. Tiberius was old and sick, but Caligula might have had a hand in his final disposition. He is said to have poisoned the old man first, and then smothered him when he wasn’t quite dead enough to give up the imperial ring.

Murderous or not, there was an auspicious beginning to his reign. The first few months were pure honeymoon. The army still loved him as Little Boot, son of the great general Germanicus, and everyone else was just so thrilled to be rid of the blood-thirsty, treason-happy degenerate Tiberius that they gloried in the dawn of a new day. He recalled the unjustly banished, stopped the censorship of certain authors, allowed magistrates to take independent action, called new elections and restored the vote, threw lavish games, cut taxes and finished public works that stingy Tiberius had defunded.

All this largesse was costly. By 39 A.D., the treasury was broke and Caligula had to resort to increasingly desperate means of fundraising, from levying new taxes to auctioning off the lives of gladiators to starting a brothel staffed by senators’ wives and daughters to executing rich men for treason and confiscating their wealth. The last two years of his reign were characterized by increasing insanity, sadism and perversion. Of course that makes for the best reading, which is why you should definitely not quit halfway through Suetonius’ Life of Caligula. He even gives you the perfect starting point. Chapter 22 begins: “So much for Caligula as emperor; we must now tell of his career as a monster.”

All this largesse was costly. By 39 A.D., the treasury was broke and Caligula had to resort to increasingly desperate means of fundraising, from levying new taxes to auctioning off the lives of gladiators to starting a brothel staffed by senators’ wives and daughters to executing rich men for treason and confiscating their wealth. The last two years of his reign were characterized by increasing insanity, sadism and perversion. Of course that makes for the best reading, which is why you should definitely not quit halfway through Suetonius’ Life of Caligula. He even gives you the perfect starting point. Chapter 22 begins: “So much for Caligula as emperor; we must now tell of his career as a monster.”

The stories of brutal murders, incest, going to war against the sea, declaring himself a god greater than all the deities in the pantheon, declaring his sisters goddesses first and then eventually killing them all, planning to make his horse Incitatus a senator and ever so much more crazy are Caligula’s primary legacy. I, Claudius draws liberally on Suetonius as does the hilariously atrocious quasi-porn movie Caligula, which started off as a legitimate film with a script by Gore Vidal starring Malcolm McDowell as Caligula and Helen Mirren as his favorite wife Caesonia, but ended up as a Bob Guccione Penthouse special.

The Senate was a favorite target of Caligula’s and over the years several senators hatched conspiracies to assassinate him. They all failed. It was officers in the Praetorian Guard, the emperor’s bodyguards, who finally did the deed in 41 A.D., apparently instigated by one too many gay jokes.

When they had decided to attempt his life at the exhibition of the Palatine games, as he went out at noon, Cassius Chaerea, tribune of a cohort of the praetorian guard, claimed for himself the principal part; for Gaius used to taunt him, a man already well on in years, with voluptuousness and effeminacy by every form of insult. When he asked for the watchword Gaius would give him “Priapus” or “Venus,” and when Chaerea had occasion to thank him for anything, he would hold out his hand to kiss, forming and moving it in an obscene fashion.

Some senators were also in on the plot. On January 24th, 41 A.D., Cassius Chaerea and some other guards approached Caligula in a passageway under his palace on the Palatine and stabbed him. Chaerea struck first, then the others took their turns, but still he lived. It took dozens of blows to kill him. Once he was dead, the guards killed his wife and their daughter.

Some senators were also in on the plot. On January 24th, 41 A.D., Cassius Chaerea and some other guards approached Caligula in a passageway under his palace on the Palatine and stabbed him. Chaerea struck first, then the others took their turns, but still he lived. It took dozens of blows to kill him. Once he was dead, the guards killed his wife and their daughter.

After his death, all the statues of Caligula (and there were lots of them because at one point Caligula had insisted that every statue be of him, going so far as to replace the heads of ancient statues of gods and heroes with portraits of him) were destroyed. The few statues that have been found of him are often in pieces.

This is how Suetonius describes him:

He was very tall and extremely pale, with an unshapely body, but very thin neck and legs. His eyes and temples were hollow, his forehead broad and grim, his hair thin and entirely gone on the top of his head, though his body was hairy. Because of this to look upon him from a higher place as he passed by, or for any reason whatever to mention a goat, was treated as a capital offence. While his face was naturally forbidding and ugly, he purposely made it even more savage, practising all kinds of terrible and fearsome expressions before a mirror.

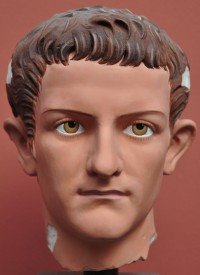

He didn’t seem to have practiced them before a sculptor. The heads of Caligula that have been found are rather mild and sweet-faced, as befits a man who died six months before his 30th birthday. One of the best preserved ones is in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen, Denmark. There are still traces of the original polychrome paint (a lot of the weathering on the white marble is actually paint remnants) on the head, which allowed experts to create a reconstruction of the original colored version.

They examined the portrait using raking light (light held at an angle almost parallel to the surface which reveals the effects of painting that impressed itself onto the marble over the centuries even though it’s gone now), ultraviolet and infrared to get as much information as possible about how the original was painted. A second head was computer-carved into marble to be an exact copy of the original, then it was painted according to the scheme determined by analysis.

I’m not seeing the goat, but he’s definitely got sunken temples and a broad forehead.

But it’s his birthday, so let’s not just wallow in Little Boot’s bad reputation. As much as the ancient sources uniformly depict Caligula as a depraved madman, they have their own agendas. It was common practice to depict notable figures fallen out of favor as hopelessly insane and sexually perverse. There’s also an echo chamber effect as the ancients borrow from each other and from original works that are now lost to us.

Some modern historians have tried, as much as possible, to sift through the limited information to reassess Caligula’s character and reign in a more objective light. For a less lurid look at this most lurid of emperors, check out the work of Sam Wilkinson, Aloys Winterling and Anthony A. Barrett.