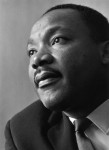

A previously unknown interview given by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1960 has been discovered in the attic of a Nashville home. Stephon Tull was looking through old boxes of his father’s when he came across a reel labeled “Dr. King interview, Dec. 21, 1960.” He borrowed an old reel-to-reel player from a friend and listened to the recording. It was of his father interviewing Martin Luther King, Jr. about the civil rights movement, the philosophy of non-violence, the political impact of that year’s sit-ins and his certainty that the child his wife Coretta was carrying would be a boy. (He was right; Dexter Scott King, Dr. King’s second son, was born just over a month later.)

A previously unknown interview given by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1960 has been discovered in the attic of a Nashville home. Stephon Tull was looking through old boxes of his father’s when he came across a reel labeled “Dr. King interview, Dec. 21, 1960.” He borrowed an old reel-to-reel player from a friend and listened to the recording. It was of his father interviewing Martin Luther King, Jr. about the civil rights movement, the philosophy of non-violence, the political impact of that year’s sit-ins and his certainty that the child his wife Coretta was carrying would be a boy. (He was right; Dexter Scott King, Dr. King’s second son, was born just over a month later.)

Tull had no idea that his father, an insurance salesman, had recorded an interview with King as part of a book he planned to write. The book would have been a first person exploration of his father’s childhood in segregated Chattanooga and his adult life in Nashville under Jim Crow and during the civil rights era. The book was never completed, and Tull’s father stored the recording in the attic. Stephon doesn’t know if anyone other than his father heard the recording before he stashed it away. His father is in his 80s now. He’s ill and is currently under hospice care, so he’s not able to fill in the blanks on this remarkable find.

Here’s the only clip I’ve been able to find from the recording:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1-T4pO2OpSQ&w=430]

Mr. Tull is asking Dr. King about the effect of the sit-ins that were held at segregated lunch counters all over the South in 1960. The sit-ins in Nashville had taken place earlier that year, from February 13th to May 10th, at the whites-only lunch counters of Woolworth’s, Walgreens and other major downtown retailers. Congressman John Lewis, then a student at Nashville’s Fisk University and of the philosophy of non-violent protest, was one of the notable participants.

The earliest sit-ins passed without incident, but as they continued they engendered increasing wrath among the business owners and segregationist crowds. By the end of February, sit-in protesters were getting arrested for disorderly conduct. The pro-segregation protesters harassing and attacking them were not. To support the sit-ins, religious leaders from Nashville’s black churches encouraged a boycott of businesses with segregated counters. An estimated 98% of Nashville’s black population participated in the boycott. Retailers promptly felt the financial sting.

The earliest sit-ins passed without incident, but as they continued they engendered increasing wrath among the business owners and segregationist crowds. By the end of February, sit-in protesters were getting arrested for disorderly conduct. The pro-segregation protesters harassing and attacking them were not. To support the sit-ins, religious leaders from Nashville’s black churches encouraged a boycott of businesses with segregated counters. An estimated 98% of Nashville’s black population participated in the boycott. Retailers promptly felt the financial sting.

On April 19th, the home of Z. Alexander Looby, a lawyer who was defending many of the demonstrators arrested at sit-ins, was bombed. He and his wife were unharmed, but the incident spurred a major protest in which 4,000 people marched on City Hall. The protest leaders met with Mayor Ben West on the courthouse steps, and he agreed publicly that segregation was immoral but said that store managers had to decide on their own whether to serve customers regardless of the color of their skin. On May 10th, a half-dozen Nashville retailers opened their lunch counters to black customers, making Nashville the first major city in the South to begin to desegregate its facilities.

It wasn’t smooth sailing from there on out, needless to say. Desegregation would remain an arduous struggle over the next four years until the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibited segregation in public places in the entire country.

Martin Luther King’s thoughts on non-violent protest and the sit-ins are well-known. He released many interviews and wrote about the topics extensively. Another subject addressed in Tull’s recording is of particular interest to historians: King’s recent trip to Africa and how the civil rights movement in the United States had an impact on the independence movements taking root on that continent.

In another part of Tull’s recording, King describes a recent trip to Africa. He explains to Tull’s father the importance of the civil rights movement both in the United States and abroad.

“There is quite a bit of interest and concern in Africa for the situation in the United States. African leaders in general, and African people in particular are greatly concerned about the struggle here and familiar with what has taken place,” he said, “We must solve this problem of racial injustice if expect to maintain our leadership in the world, and if we expect to maintain a moral voice in a world that is two thirds color.”

According to Clayborne Carson, founding director of Stanford University’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, King is talking about a trip to Nigeria he took in November of 1960, just a month before the Tull interview. King was personally invited to Lagos by Nnamdi Azikiwe, Nigeria’s first governor-general of African descent, to attend his inauguration on November 16th, 1960. In 1963, Azikiwe would become the first president of the independent Republic of Nigeria.

Carson notes that there isn’t very much information out there about the Nigeria trip. King didn’t do any interviews or press conferences while he was there, nor does he talk about the Nigerian trip in any extant letters or documents. The Tull interview is a rare gem on that score.

Stephon Tull is planning to sell the recording through collector and broker Keya Morgan in New York City. Will it fall into the private abyss or will a museum, the King Center or another institution get to preserve it for posterity?