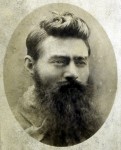

The skeletal remains of 19th century Australian folk hero outlaw Ned Kelly were discovered in a mass grave on the site of the former Pentridge Prison in 2008. Unlike many of the more than 30 executed criminals buried in that grave, Kelly’s bones — minus the skull which is still missing — were in a box of their own, so experts from the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine were able to examine them without having to sort out which bones amidst the jumble of bones belonged together. They were able to confirm that the skeleton bore the marks of wounds Ned Kelly had incurred on that fateful day in 1880 at the Glenrowan Inn when police finally caught him after a shootout; namely, partially healed gunshots in his toe, left elbow, and wrist and the shot to the shin that took him down.

The skeletal remains of 19th century Australian folk hero outlaw Ned Kelly were discovered in a mass grave on the site of the former Pentridge Prison in 2008. Unlike many of the more than 30 executed criminals buried in that grave, Kelly’s bones — minus the skull which is still missing — were in a box of their own, so experts from the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine were able to examine them without having to sort out which bones amidst the jumble of bones belonged together. They were able to confirm that the skeleton bore the marks of wounds Ned Kelly had incurred on that fateful day in 1880 at the Glenrowan Inn when police finally caught him after a shootout; namely, partially healed gunshots in his toe, left elbow, and wrist and the shot to the shin that took him down.

It wasn’t until last year, however, that a mitochondrial DNA match with a great-grandnephew of Kelly’s established beyond question that the skeleton was all that remained of Ned Kelly. Once the determination was conclusively made, the government of the state of Victoria said it would return the skeleton to Kelly’s descendants for burial as they saw fit. There was some discussion of a public memorial service, some queasy back-and-forth with police representatives who were appalled at the idea of celebrating the life of a cop-killer, and debate over the potential tourist revenue vs. the distaste of Ned Kelly fans making a shrine out of his new grave.

It wasn’t until last year, however, that a mitochondrial DNA match with a great-grandnephew of Kelly’s established beyond question that the skeleton was all that remained of Ned Kelly. Once the determination was conclusively made, the government of the state of Victoria said it would return the skeleton to Kelly’s descendants for burial as they saw fit. There was some discussion of a public memorial service, some queasy back-and-forth with police representatives who were appalled at the idea of celebrating the life of a cop-killer, and debate over the potential tourist revenue vs. the distaste of Ned Kelly fans making a shrine out of his new grave.

Then it all came to a screeching halt when real estate developer Leigh Chiavaroli, owner of Pentridge Village, the company that owns the area of Pentridge Prison where the mass grave was discovered, laid claim to the remains. They were found on his property, was his argument; therefore they were his, and he wanted to keep them to put them on public display in a museum on the site. He also wanted three million Australian dollars in compensation for the building delays caused by the excavation of the mass grave.

Then it all came to a screeching halt when real estate developer Leigh Chiavaroli, owner of Pentridge Village, the company that owns the area of Pentridge Prison where the mass grave was discovered, laid claim to the remains. They were found on his property, was his argument; therefore they were his, and he wanted to keep them to put them on public display in a museum on the site. He also wanted three million Australian dollars in compensation for the building delays caused by the excavation of the mass grave.

The prospect of their ancestor’s bones being made a public spectacle appalled Ned Kelly’s relations. As it is, his body had not been treated with anything like decency, from the moment of his death onward. On November 10th, 1880, the day before his hanging, Ned Kelly dictated a letter to the colonial Governor of Victoria, George Phipps, 2nd Marquess of Normanby, that closed with his last wishes. He couldn’t write the letter himself because of the gunshot wound to his wrist, so William Buck, warder at Melbourne Gaol where Kelly was imprisoned, hanged and initially buried, wrote it for him. Ned signed it with his mark, a large X over his name. You can see a photocopy of the complete letter here, and, courtesy of the Public Records of Victoria website, you can download a huge image of the entire Kelly capital case file here. The letter in question is about halfway down. His final requests are just above the signatures in that letter:

I have been found guilty and condemned to death on a charge of all men in the world I should be the last one to be guilty of. There is one wish in conclusion I would wish you to grant me, that is the release of my Mother before my execution as detaining her in prison could not make any difference to the forementioned. For the day will come when all men will be judged by their mercy and deeds and also if you would grant permission for my friends to have my body that they might bury it in Consecrated ground.

His mother Ellen Kelly was also imprisoned in Melbourne Gaol at that time, condemned to three years hard labour for her supposed role (the charges were widely seen as trumped up in retaliation against her son) in the attempted murder of a police constable. Neither of his final wishes was granted. His mother served her full term, 1878-1881, and Ned’s body was not buried in consecrated ground. It wasn’t even just peaceably buried.

His mother Ellen Kelly was also imprisoned in Melbourne Gaol at that time, condemned to three years hard labour for her supposed role (the charges were widely seen as trumped up in retaliation against her son) in the attempted murder of a police constable. Neither of his final wishes was granted. His mother served her full term, 1878-1881, and Ned’s body was not buried in consecrated ground. It wasn’t even just peaceably buried.

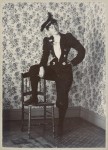

Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine experts found the marks of a cutting saw on some of the bones, proving that despite all their vehement public denials, the authorities at Melbourne Gaol had allowed his corpse to be dissected. By law, dissection was only allowed in case of a coroner’s inquest when it was necessary to determine cause of death. It was a big scandal at the time that Ned Kelly’s mortal remains had been so violated against custom and law.

Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine experts found the marks of a cutting saw on some of the bones, proving that despite all their vehement public denials, the authorities at Melbourne Gaol had allowed his corpse to be dissected. By law, dissection was only allowed in case of a coroner’s inquest when it was necessary to determine cause of death. It was a big scandal at the time that Ned Kelly’s mortal remains had been so violated against custom and law.

His skull had been given to phrenologists to make an in-depth “scientific” study of and then returned to the police, who used it as a paperweight. When the contents of the Melbourne Gaol graves were moved to Pentridge Prison in 1929, workers took a skull they thought was Ned Kelly’s and kept it for decades. The police kept theirs for decades too, but by the time both skulls wound up in the hands of experts at the Australian Institute of Anatomy in the 1970s, experts found that neither skull was Ned’s. Ned Kelly’s skull remains on the lam.

On Wednesday, August 1st, the Victoria State Government stopped the rollercoaster Ned Kelly’s bones have been riding. They issued a new exhumation license for his remains, a legal maneuver that ensures the Kelly descendants will receive his remains.

They will bury what’s left of Ned in consecrated ground, as he asked, probably in Greta Cemetery where Ned’s mother Ellen is buried. The descendants have to make the decision as a group so there’s some discussion to be done before the details are pinned down, but it seems likely that they’ll opt for a private burial ceremony.