The low salinity and cold temperatures of the Baltic Sea provide ideal conditions for the preservation of shipwrecks and their contents. There are an estimated 100,000 shipwrecks resting on the floor of the Baltic Sea, with perhaps 6,000 of them deemed of particular archaeological and historical significance. Although Swedish Baltic archaeological finds have made much of the news lately, there are approximately 1,500 protected marine monuments (mostly shipwrecks, but also some downed aircraft and submerged archaeological remains that were once on dry land) in German Baltic waters.

The low salinity and cold temperatures of the Baltic Sea provide ideal conditions for the preservation of shipwrecks and their contents. There are an estimated 100,000 shipwrecks resting on the floor of the Baltic Sea, with perhaps 6,000 of them deemed of particular archaeological and historical significance. Although Swedish Baltic archaeological finds have made much of the news lately, there are approximately 1,500 protected marine monuments (mostly shipwrecks, but also some downed aircraft and submerged archaeological remains that were once on dry land) in German Baltic waters.

Before the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, these were mainly left alone. Much of the coastal Baltic was restricted territory. Except for a few select people, divers weren’t allowed to explore the vast historical wealth under water. Since reunification, areas that were once off limits are now open, and advances in diving technology have greatly increased the numbers of sports divers hoping to see the Baltic sights. They can also go further offshore to reach shipwrecks that 20 years ago wouldn’t have been accessible. Add to that a wider range of available tools for the sports diver, and now stealing objects of historical value from Baltic wrecks becomes a lucrative proposition.

Only 350 of the marine monuments have been officially explored and mapped, which makes it hard to know exactly how bad the undersea looting situation has gotten. The evidence on the sites that have been documented, however, is extremely disturbing. For example, one World War II U-boat, a small two-man vessel discovered 60 feet under Baltic waters off the coast of Boltenhagen in 2000, was found with its turret hatch closed and undamaged. It was therefore designated a war grave, since its crew remained sealed within. In 2002, divers broke into the hatch. Regional government officials sealed the hole with a steel plate which is still in place today, but shows clear signs of having been tampered with in an attempt to break into the U-boat.

Only 350 of the marine monuments have been officially explored and mapped, which makes it hard to know exactly how bad the undersea looting situation has gotten. The evidence on the sites that have been documented, however, is extremely disturbing. For example, one World War II U-boat, a small two-man vessel discovered 60 feet under Baltic waters off the coast of Boltenhagen in 2000, was found with its turret hatch closed and undamaged. It was therefore designated a war grave, since its crew remained sealed within. In 2002, divers broke into the hatch. Regional government officials sealed the hole with a steel plate which is still in place today, but shows clear signs of having been tampered with in an attempt to break into the U-boat.

“It’s one of our big worries, over the years people keep trying to get into it and that is of course utterly disrespectful,” says Detlef Jantzen, an archaeologist at the regional agency for monument protection in the northeastern German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

It’s possible that these divers don’t realize the U-boat is a war grave, or at least aren’t consciously thinking about the fact that they’re desecrating a grave by messing with the hatch. Some of the other wreck sites that are regularly visited by hobby divers may be damaged because the tourists with good intentions don’t understand how their interactions with the artifacts can cause harm. In an attempt to appeal to better natures, and maybe to enlist conditioned reactions to museum signs, Germany’s Society of Maritime Archaeology has started a project to add underwater signs to historic shipwrecks.

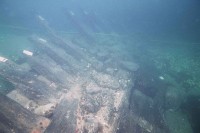

Last week the first sign was added to a 100-year-old tugboat thought to have been sunk during or just after World War II. At only 30 feet deep, it’s a popular site for sport divers to visit. The wreck was discovered three years ago and is already showing the ill-effects of diver interference. The sign informs divers that the wreck is a protected historical monument and provides additional information about the site’s layout and history.

Last week the first sign was added to a 100-year-old tugboat thought to have been sunk during or just after World War II. At only 30 feet deep, it’s a popular site for sport divers to visit. The wreck was discovered three years ago and is already showing the ill-effects of diver interference. The sign informs divers that the wreck is a protected historical monument and provides additional information about the site’s layout and history.

The group will start by signposting nine monuments. One particularly valuable wreck is that of the “Darsser Kogge,” a 14th century ship that is a rare example of medieval shipbuilding. “It’s lying on its side and the remains provide valuable information on construction and manufacturing techniques of the time,” said [Society of Maritime Archaeology chairman Martin] Siegel. “These preserved vessels are often the only source of research into traditional shipbuilding.”

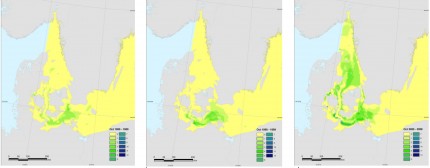

The Darsser Kogge has enough to worry about as it is without divers making things worse. The Baltic Sea is increasingly subject to the depredations of the dreaded Teredo navalis, naval shipworm, which used to stick to saltier waters leaving Baltic wooden wrecks free of its destructive devouring. As the waters of the Baltic have gotten warmer and their salinity has increased, particularly over the past decade, the wood boring creatures have spread from the coast of Denmark east into German Baltic territory and north into Swedish waters.

The EU has funded a study of the presence of shipworm in the Baltic, the Wreck Protect Project, to determine how far Teredo navalis has spread, whether, as researchers suspect, climate change is the underlying cause of the Baltic’s environmental changes, and how best to preserve archaeological and historical sites in situ, since logistics and funding make it impossible to contemplate raising every wreck for conservation on dry land.

The EU’s MoSS (Monitoring Safeguarding and Visualizing North European Shipwreck Sites) Project worked to document and protect four wreck sites in the Baltic and elsewhere in Northern Europe, including the Darsser Kogge. There are some good pictures and information about the history of the ship and its conservation challenges on its website.

The EU’s MoSS (Monitoring Safeguarding and Visualizing North European Shipwreck Sites) Project worked to document and protect four wreck sites in the Baltic and elsewhere in Northern Europe, including the Darsser Kogge. There are some good pictures and information about the history of the ship and its conservation challenges on its website.