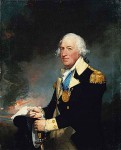

General Horatio Gates was the commanding general at the Battle of Saratoga, which took place in eastern New York in two phases on September 19th and October 7th, 1777. The conclusive victory resulted in the surrender of British General John Burgoyne’s army and was the immediate cause of France’s agreement to negotiate an alliance with the ragtag colonists, which would force Britain to fight on multiple fronts and would provision the Revolutionaries with much-needed arms and money. The Battle of Saratoga is widely considered America’s greatest victory in the War of Independence.

General Horatio Gates was the commanding general at the Battle of Saratoga, which took place in eastern New York in two phases on September 19th and October 7th, 1777. The conclusive victory resulted in the surrender of British General John Burgoyne’s army and was the immediate cause of France’s agreement to negotiate an alliance with the ragtag colonists, which would force Britain to fight on multiple fronts and would provision the Revolutionaries with much-needed arms and money. The Battle of Saratoga is widely considered America’s greatest victory in the War of Independence.

For some time after Saratoga, General Gates was held in the highest esteem. He and George Washington were treated as equally great heroes, appearing on the cover of almanacs and in contemporary histories as luminaries of the Continental Army. Then things went awry, which is why few people have heard of Gates today while we daily palpate George Washington’s visage on the dollar bill. The main problem was that General Gates had a gigantic ego which led him to take more credit than he may have deserved, and to attempt to secure more power than was wise.

Born in 1727 in Deptford, England, Horatio Gates was the son of a housekeeper with outstanding connections to the aristocracy and a civil servant. His mother’s service for the Duke of Bolton secured a military commission for her son, who ten years later would move to New York and serve under British General Edward Braddock in the French and Indian War. An injury early on in the campaign kept him from doing much field duty, but by all accounts he was an excellent military administrator.

Born in 1727 in Deptford, England, Horatio Gates was the son of a housekeeper with outstanding connections to the aristocracy and a civil servant. His mother’s service for the Duke of Bolton secured a military commission for her son, who ten years later would move to New York and serve under British General Edward Braddock in the French and Indian War. An injury early on in the campaign kept him from doing much field duty, but by all accounts he was an excellent military administrator.

By 1769, he was over the British army with its strict class-based promotion system that had kept him stuck at the rank of major for years. He sold his commission and bought a small plantation outside Leetown in what was then Virginia and is now West Virginia. When hostilities broke out with Britain in 1775, Gates immediately presented himself to Washington, whom he had known when they both served under Braddock in the French and Indian War, as an experienced candidate for high rank in the nascent US army. Valuing his inside knowledge of British military tactics and his administrative abilities, Washington appointed him Brigadier General and Adjutant General of the Continental Army.

Gates wanted a field command, though. In fact, he wanted the whole command, actively lobbying the Continental Congress in 1776 to appoint him Commander-in-Chief instead of Washington. He had many influential backers, especially among the New England delegates, but Washington’s victories at Trenton (after he famously crossed the icy Delaware River standing up in the front of a rowboat) on December 26th, 1776 and at Princeton on January 2nd, 1777 entrenched his position at the head of the army. General Gates was sent to New York State to help Major General Philip Schuyler, commander of the army’s Northern Department.

When Schuyler lost Fort Ticonderoga to the British, Gates saw his chance (even though he was plenty involved in the failed campaigns). Congress appointed him commander of the Northern Department in August of 1777, a month before the initial encounters with General Burgoyne’s troops at Saratoga.

There is much debate on the question of how much credit he deserves for the victory there. His field generals, most notably Benedict Arnold, did much of the on-the-ground fighting, and Arnold’s greatest success repelling a British attack on the left flank happened against Gates’ orders. Arnold was shot in the leg in that battle. The shot broke his leg and killed his horse, which then fell on top of him and broke his leg some more.

There is much debate on the question of how much credit he deserves for the victory there. His field generals, most notably Benedict Arnold, did much of the on-the-ground fighting, and Arnold’s greatest success repelling a British attack on the left flank happened against Gates’ orders. Arnold was shot in the leg in that battle. The shot broke his leg and killed his horse, which then fell on top of him and broke his leg some more.

Gates liked his action defensive, always advocating for retreat and holding back. It’s not as glamorous as Arnold’s inspiring charge into the breach, but in this case Gates’ cautiousness served the troops well since it ensured they were well-established in a defensive position on Bemis’ Heights with solid supply lines all the way back to Albany. The British Army, on the other hand, had major supply issues and although they had won the first encounter in September, they did so at great human cost, particularly among their officers who had been successfully targeted by American shooters. The American army was able to cut off British resupply, and the German troops refused Burgoyne’s orders to attack again. On October 17th, Burgoyne surrendered to Gates.

Riding high on the Saratoga victory, Gates was appointed head of the Board of War, a civilian position which put him in the absurdly conflict-rife position of having political command over George Washington who was his commanding officer in the army. During this time, he and a cabal of officers, including General Thomas Conway, discussed having Washington fired and Gates appointed Commander-in-Chief in his place. It never went beyond an exchange of letters, and the Conway Cabal, as it became known, failed when Washington found out about it and confronted the grumblers. Gates apologized, resigned from the Board of War, and quietly took command of the Eastern Department.

Riding high on the Saratoga victory, Gates was appointed head of the Board of War, a civilian position which put him in the absurdly conflict-rife position of having political command over George Washington who was his commanding officer in the army. During this time, he and a cabal of officers, including General Thomas Conway, discussed having Washington fired and Gates appointed Commander-in-Chief in his place. It never went beyond an exchange of letters, and the Conway Cabal, as it became known, failed when Washington found out about it and confronted the grumblers. Gates apologized, resigned from the Board of War, and quietly took command of the Eastern Department.

In 1780, he was given command of the Southern Department after the British victory in the Siege of Charleston, South Carolina. This would turn out to be his military nadir. At the Battle of Camden on August 16th, Gates’ army was beaten like a red-headed stepchild by General Charles Cornwallis. The British took 1,000 of Gates’ men prisoner and all of his artillery. Gates reputedly distinguished himself in one way: by running 170 miles in three days on horseback to get back to safety up north.

Congress called for an inquiry into Gates’ conduct in the aftermath of the disaster, but it went nowhere and his supporters had it repealed in 1782. With the end of hostilities in 1783, you’d think his chances to mess up would also end, but Gates was involved in one more embarrassment, the Newburgh conspiracy, in which officers unhappy about the prospect of their promised pensions remaining unpaid due to Congressional brokeness tried to stir up trouble. They proposed Washington be replaced by Gates, but Washington yet again headed them off at the pass by delivering a speech which, though unpersuasive in substance, swayed his officers back to his side with a reference to his now having to wear glasses because of the hardships he’d suffered along with them during this war.

Gates went back to Traveler’s Rest, his estate in Virginia, for a few years. Then he sold the estate, manumitted his slaves, and moved to New York. He died in Manhattan in 1806 and was buried in the Trinity Church graveyard on Wall Street. Doubtless he had a gravestone at that point, but over time it was lost, as was the exact location of his burial.

Gates went back to Traveler’s Rest, his estate in Virginia, for a few years. Then he sold the estate, manumitted his slaves, and moved to New York. He died in Manhattan in 1806 and was buried in the Trinity Church graveyard on Wall Street. Doubtless he had a gravestone at that point, but over time it was lost, as was the exact location of his burial.

Now, thanks to the efforts of James S. Kaplan, a tax attorney/historian/tour guide who for the past 16 years has given a walking tour of Revolutionary War sites in Manhattan every July 4th from 2:00 AM to 6:00 AM, and the Daughters of the American Revolution, General Horatio Gates has an official memorial marker at the Trinity Church cemetery. The marble marker was installed on the south side of the church and a wreath lain in a ceremony on Sunday, October 21st.

Now, thanks to the efforts of James S. Kaplan, a tax attorney/historian/tour guide who for the past 16 years has given a walking tour of Revolutionary War sites in Manhattan every July 4th from 2:00 AM to 6:00 AM, and the Daughters of the American Revolution, General Horatio Gates has an official memorial marker at the Trinity Church cemetery. The marble marker was installed on the south side of the church and a wreath lain in a ceremony on Sunday, October 21st.

Read James Kaplan’s assessment of General Gates’ role in the Battle of Saratoga in this article. You can listen to James Kaplan’s Trinity Church tour here. Search for “Kaplan” on this page to access recordings of his many other tours of New York City, including his ten-stop Great Crash of 1929 tour of Wall Street in collaboration with real estate executive Richard M. Warshauer.