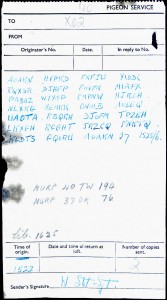

A member of an informal group dedicated to researching local history in Ontario thinks he’s cracked the code found on the remains of a World War II carrier pigeon, the code that the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), Britain’s code-breaking unit, declared virtually unbreakable just three weeks ago.

Gord Young, of Lakefield Heritage Research in Peterborough, Ontario, thought the GCHQ and Bletchley Park experts were overthinking the issue. He decided to use the World War I Royal Flying Corp aerial observers’ book he had inherited from his great-uncle to see if the pigeon’s message was more simple than anyone expected. Seventeen minutes later, he had a coherent deciphered message. To whit:

Gord Young, of Lakefield Heritage Research in Peterborough, Ontario, thought the GCHQ and Bletchley Park experts were overthinking the issue. He decided to use the World War I Royal Flying Corp aerial observers’ book he had inherited from his great-uncle to see if the pigeon’s message was more simple than anyone expected. Seventeen minutes later, he had a coherent deciphered message. To whit:

Artillery observer at ‘K’ Sector, Normandy. Requested headquarters supplement report. Panzer attack – blitz. West Artillery Observer Tracking Attack.

Lt Knows extra guns are here. Know where local dispatch station is. Determined where Jerry’s headquarters front posts. Right battery headquarters right here.

Found headquarters infantry right here. Final note, confirming, found Jerry’s whereabouts. Go over field notes. Counter measures against Panzers not working. Jerry’s right battery central headquarters here. Artillery observer at ‘K’ sector Normandy. Mortar, infantry attack panzers.

Hit Jerry’s Right or Reserve Battery Here. Already know electrical engineers headquarters. Troops, panzers, batteries, engineers, here. Final note known to headquarters.

That’s not the entire message. Gord was unable to decipher some parts of it which he thinks may be specialized World War II acronyms which his World War I code book obviously can’t cover. They could also be “fillers,” nonsense added deliberately to confuse the enemy in case the messages was interception.

As for why a World War II soldier would have been using a World War I code, Young speculates that the sender’s trainer was a World War I veteran, a “former Artillery observer-spotter.” He deduced this based on the “Serjeant” spelling of the sender’s rank, a holdover from WWI. I’ve read conflicting reports on the whole “Serjeant” issue, whether it denoted RAF over artillery or just some specialized artillery units or now this World War I trainer theory. I don’t have the expertise to weigh their plausibility.

GCHQ, who released a statement on November 22nd entitled “Pigeon takes secret message to the grave,” says it’s interested in examining Young’s work but remains insistent that they were right to give up after three weeks.

“We stand by our statement of 22 November 2012 that without access to the relevant codebooks and details of any additional encryption used, the message will remain impossible to decrypt,” he said.

“Similarly it is also impossible to verify any proposed solutions, but those put forward without reference to the original cryptographic material are unlikely to be correct.”

Somebody’s defensive. Not that Young couldn’t be completely wrong, of course, but it seems to me the odds are very slim that he’d have been able come up with something relevant and cogent if his code book was way off-base.

I’m not sure where they’re getting it, but several articles about the putative code-breaking also include new information about the sender, Sjt Stot. Apparently Sergeant William Stott was a paratrooper with the Lancashire Fusiliers. He was 27 years old when he (and some pigeons, apparently) parachuted behind enemy lines in Normandy on a mission to assess the strength of German forces. He was killed in action just weeks after the message was sent and is buried in a war cemetery in Normandy.