The violent culmination of the epic feud between the Hatfields and the McCoys took place in the hilly woodlands of Pike County, Kentucky, in the wee hours of New Year’s Day 1888. While it was still dark, a group of nine Hatfields led by Uncle Jim Vance surrounded Randolph McCoy’s cabin and opened fire on the family slumbering within. The McCoys returned fire through the second floor windows and the front door, but were forced to flee when the Hatfields set the cabin on fire.

The violent culmination of the epic feud between the Hatfields and the McCoys took place in the hilly woodlands of Pike County, Kentucky, in the wee hours of New Year’s Day 1888. While it was still dark, a group of nine Hatfields led by Uncle Jim Vance surrounded Randolph McCoy’s cabin and opened fire on the family slumbering within. The McCoys returned fire through the second floor windows and the front door, but were forced to flee when the Hatfields set the cabin on fire.

Randolph himself managed to escape with some of his children, but his son Calvin and his daughter Alifair were killed in the assault. His wife Sarah was beaten into unconsciousness. The brutal New Year’s Night Massacre, as it became known, made the news all over the country and although two more people would die over the next few weeks and one would be hanged two years later for the murder of Alifair, New Year’s Day 1888 marked the final turning point in the feud.

The exact location of Randolph’s cabin was forgotten over the years. Bob Scott, a descendant of the Hatfields, today owns the land in the hills of Pike County where the cabin was generally known to have been. His parents and grandparents told him stories about the property and its role in the feud. Last year, National Geographic’s metal detecting Diggers, together with local historian Bill Richardson explored the area where according to family lore the McCoy cabin once stood.

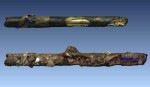

They were successful. The Diggers team found three different kinds of bullets, including shotgun pellets, buried into the hillside in an area about 30 feet wide. The ammunition dates to the time of the shootout. Experts believe this bullet-riddled area is across from the front of the cabin since that was the epicenter of the exchange of fire. It matches the oral histories which record the McCoy’s shooting back at the Hatfields from the upper windows and front door. They also found a piece of charred wood with a nail in it that matches the period of the cabin.

They were successful. The Diggers team found three different kinds of bullets, including shotgun pellets, buried into the hillside in an area about 30 feet wide. The ammunition dates to the time of the shootout. Experts believe this bullet-riddled area is across from the front of the cabin since that was the epicenter of the exchange of fire. It matches the oral histories which record the McCoy’s shooting back at the Hatfields from the upper windows and front door. They also found a piece of charred wood with a nail in it that matches the period of the cabin.

These initial discoveries were later confirmed by a team from the Kentucky Archaeological Survey led by archaeologist Dr. Kim McBride. They found fragments of window glass and ceramics from the period of the New Year’s Night Massacre and additional charred wood and nails. They also found supporting documentary evidence.

“This is an incredible discovery behind America’s greatest family feud,” [McBride] said in a recent press release from National Geographic. “After spending two days excavating at the site, we were pleased to find a number of original artifacts from the actual structure, such as window glass and both wrought and machine-cut nails, and we were able to trace the lineage of the property right back to Randall McCoy and his wife, Sarah McCoy. As archaeologists, we are very excited to find real evidence to back theories that have abounded for decades.”

According to McBride, the experience was an unlikely pairing of metal detecting enthusiasts with professional archaeologists, but the partnership demonstrated that the two groups can work together to find and properly document artifacts in a scientific manner benefiting both interests. The effort to find material evidence associated with the McCoy homestead was initiated by the “Diggers” team; however, the discovery of the artifacts would have had little meaning without the additional systematic investigations and recovery of other artifacts by trained archaeologists who could interpret them within the context of where and how they were found, she said.

The first airing of the Diggers episode was January 29th, but there are reruns aplenty to catch. The next airing is Friday, February 1st at 1:10 PM EST. There are some clips available online, but not the entire episode.

The history of the Hatfields and McCoys has seen a resurgence of popularity since the History channel miniseries broke cable viewing records. Bob Scott plans to take advantage of the historic find on his property by developing it for tourism. One of the options he’s apparently considering is a housing development with horseback and ATV trails, which sounds sort of hideous to me so I hope it doesn’t happen.