The remains of a large commercial harbour complex dating back to the Fourth Dynasty 4,500 years ago have been discovered at Wadi el-Jarf, a town on the Red Sea shore 110 miles south of Suez city, Egypt. Inscriptions and radiocarbon dating of pottery date the site to the reign of the pharaoh Khufu (aka Cheops). The port was one of a network on both sides of the Gulf of Suez used to transport limestone blocks from the quarries and copper and turquoise from the mines in south Sinai back to the Nile Valley. It’s the earliest found to date, the oldest commercial port found in Egypt and according to Sorbonne Egyptologist and excavation director Pierre Tallet, the oldest commercial port ever found anywhere, predating any others by 1,000 years.

Archaeologists from the French Institute for Archaeological Studies (IFAO) found a long L-shaped quay that starts on the beach and runs east under water for 525 feet before turning southeast for 394 feet. It appears to have been a breakwater structure that protected moored ships from the strong winds and powerful north-south currents of the Red Sea coast. Inside the protected area researchers found 24 pharaonic anchors. Made out of limestone, the anchors are carved into triangular, rectangular and cylindrical shapes with a hole in the upper section. Many of them were found in pairs which suggests deliberate placement rather than haphazardly discarded ship accessories. That’s why researchers believe they were stationed permanently in the water so that ships in transit could be moored to them.

This is an exciting find because although Egyptian anchors have been discovered before, most of them date to the Middle Kingdom and had been put to new uses. These are the first ancient anchors found in situ where they did their original anchor duty. It’s the oldest and largest collection of early Bronze Age anchors ever discovered.

This is an exciting find because although Egyptian anchors have been discovered before, most of them date to the Middle Kingdom and had been put to new uses. These are the first ancient anchors found in situ where they did their original anchor duty. It’s the oldest and largest collection of early Bronze Age anchors ever discovered.

The harbour complex continues inland. Even more anchors (99 of them, to be specific) were found in the remains of a light camp installation about 650 feet from the shore. There were hieroglyphic inscriptions on some of the anchors which Tallet believes were the name of the boat to which they once belonged. There’s a mound of limestone blocks nearby which was probably used as a visual landmark.

A mile and a quarter inland from the mound are the remains of an isolated rectangular building about 200 feet long and 100 feet wide. The building is divided into 13 elongated cell-like rooms. Its function is unknown but we do know it’s the largest pharaonic building found on the Red Sea coast.

Just over two and a half miles from the shore at the at the foot of the mountains are groups of camps and what may be defensive surveillance installations. The largest of them has a complex of rectangular structures with cell-like rooms that were probably living spaces for the workers.

Three miles from the shore, just south of the camps is a system of 25 to 30 galleries carved into the bedrock. The galleries are not a new find; they were first discovered in 1823 by British Egyptologists Sir John Garner Wilkinson and James Burton who thought they were catacombs. There was no follow-up until 1954 when French researchers François Bissey and René Chabot-Morisseau began to explore the area only to be stopped before they really got going by the Suez crisis. Tallet’s team used Bissey and Chabot-Morisseau’s notes and Google Earth satellite images to find the site when their project began in 2008.

Three miles from the shore, just south of the camps is a system of 25 to 30 galleries carved into the bedrock. The galleries are not a new find; they were first discovered in 1823 by British Egyptologists Sir John Garner Wilkinson and James Burton who thought they were catacombs. There was no follow-up until 1954 when French researchers François Bissey and René Chabot-Morisseau began to explore the area only to be stopped before they really got going by the Suez crisis. Tallet’s team used Bissey and Chabot-Morisseau’s notes and Google Earth satellite images to find the site when their project began in 2008.

Excavations began in 2011 on four of the galleries. The team found that the galleries were not catacombs; they were storage facilities used to keep dismantled boats safe from the elements. Pieces of ropes, textiles, large pieces of wood, fragments of cedar beams, a piece of boat timber nine feet wide, the end of an oar were discovered in the galleries. The galleries range in length from 52 feet to 112 feet and are an average of 10 feet wide and seven feet high. They were not carved haphazardly at different times, but according to a pre-planned layout. Access to the galleries was protected by causeways of monumental stone blocks. The entrances were closed and opened by an elaborate portcullis system of large limestone blocks similar to the ones used during Fourth Dynasty funerary structures. The blocks were inscribed with the Khufu’s name written in red ink.

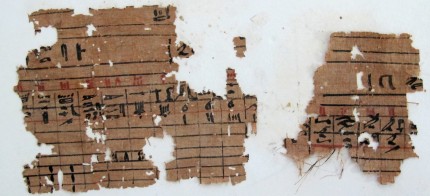

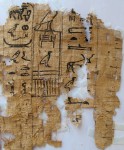

Inside the storage galleries archaeologists made another major find: hundreds of papyrus fragments, 10 of them in very good condition. These are the oldest papyri ever found. They’re a social history bonanza, describing the administration of the harbour complex during the 27th year of Khufu’s reign. There are monthly reports on the number of harbour workers, on how they were supplied with bread and beer. Perhaps most riveting of all the papyri is a diary that describes the work of gathering limestone for the construction of the Great Pyramid. From the Discovery News slideshow of the finds:

Inside the storage galleries archaeologists made another major find: hundreds of papyrus fragments, 10 of them in very good condition. These are the oldest papyri ever found. They’re a social history bonanza, describing the administration of the harbour complex during the 27th year of Khufu’s reign. There are monthly reports on the number of harbour workers, on how they were supplied with bread and beer. Perhaps most riveting of all the papyri is a diary that describes the work of gathering limestone for the construction of the Great Pyramid. From the Discovery News slideshow of the finds:

[I]t’s the diary of Merrer, an Old Kingdom official involved in the building of the Great Pyramid of Cheops.

From four different sheets and many fragments, the researchers were able to follow his daily activity for more that three months.

“He mainly reported about his many trips to the Turah limestone quarry to fetch block for the building of the pyramid,” Tallet said.

“Although we will not learn anything new about the construction of Cheops monument, this diary provides for the first time an insight on this matter,” Tallet said.

I love how it’s a fully graphed out table, a spreadsheet in hieroglyphics. The papyri are now in the Suez museum where they will be conserved, catalogued and studied.

The harbour complex was definitely Khufu’s baby, used during his reign and for a few decades later. Pottery evidence indicates that the installations were occupied primarily during the first half of the Fourth Dynasty. There are some traces that parts of the complex were still in use in the beginning of the Fifth Dynasty, 72 years after Khufu’s death, but after that it was abandoned.