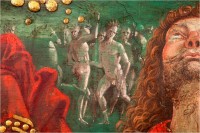

A new restoration of Resurrection, a fresco by Renaissance master Pinturicchio in the Vatican’s Borgia Apartment, has revealed what may the first images of Native Americans in European art. After cleaning the fresco, art restorer Maria Pustka found that some previously indistinct, distant figures in the middle of the composition beneath the risen Christ and a Roman soldier looking up in awe are nude males wearing feather headdresses whose postures suggest they are dancing. Since Pinturicchio painted Pope Alexander VI’s suite of rooms between 1492 and 1494, these could well be the artist’s vision of the friendly naked natives bedecked in parrots that Columbus described upon his return from the first voyage.

A new restoration of Resurrection, a fresco by Renaissance master Pinturicchio in the Vatican’s Borgia Apartment, has revealed what may the first images of Native Americans in European art. After cleaning the fresco, art restorer Maria Pustka found that some previously indistinct, distant figures in the middle of the composition beneath the risen Christ and a Roman soldier looking up in awe are nude males wearing feather headdresses whose postures suggest they are dancing. Since Pinturicchio painted Pope Alexander VI’s suite of rooms between 1492 and 1494, these could well be the artist’s vision of the friendly naked natives bedecked in parrots that Columbus described upon his return from the first voyage.

Vatican Museums Director Antonio Paolucci posits in an article in the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano that perhaps the Borgia Pope got his hands on a copy of the diary Columbus kept on his first voyage. According to Paolucci, Columbus gave this journal to their Most Catholic Majesties King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella who tried to keep it quiet for political reasons but since the pope was Spanish, he probably heard about it anyway.

I think he’s confusing Columbus’ journal, later edited by Bartolomé de las Casas but not published until 1825, with a letter Columbus wrote about the new islands in Southeast Asia he thought he’d discovered. It wasn’t a secret, though. It was an international sensation.

I think he’s confusing Columbus’ journal, later edited by Bartolomé de las Casas but not published until 1825, with a letter Columbus wrote about the new islands in Southeast Asia he thought he’d discovered. It wasn’t a secret, though. It was an international sensation.

While still on board the Niña as it approached the Iberian peninsula in mid-February, Columbus wrote the letter to Ferdinand and Isabella reporting his findings. Either when he landed in Lisbon on March 4th or the harbour of Palos on March 15, 1493, Columbus sent the letter to the king and queen and a copy to Luis de Santangel, Ferdinand II’s finance minister who had raised all the money for the voyage and convinced their majesties to approve of Columbus’ plan. He may also have sent a third to Gabriel Sanchez, Treasurer of Aragon; there’s a fair amount of confusion about the recipients and the sources of the copies.

Although there is some evidence that the King and Queen weren’t keen to have the letter get out — no copies of their majesties’ letter were ever published — by early April, a printed copy the Santangel letter was published in Spain. In May, a Latin translation was circulating in Rome, and the Latin version spread to cities all over Europe within weeks. It had already been set to Italian verse by June, 1493. You can read an English translation here.

Pope Alexander VI certainly saw the Latin version of the letter in Rome, and in any case by then he was fully versed in the discovery because he had to arbitrate between Portugal and Spain on the question of who got to claim the New World. Portugal asserted that the new territories belonged to the Portuguese crown, despite the fact that Spanish ships had made the discovery, because previous papal bulls had granted Portugal extremely broad rights to any dominions populated by non-Christians. Romanus Pontifex, for example, issued in 1455 by Pope Nicholas V, stipulated that the King Alfonso and his heirs had exclusive dominion over all lands and seas “though situated in the remotest parts unknown to us, and subject them to their own temporal dominion” and that no other power, ecclesiastical or temporal, may interfere with this great Christianizing conquest in any way.

Ferdinand and Isabella accepted the previous bulls, but asked Pope Alexander VI to review the question. The pope was Valencian now, so they figured, correctly as it happened, that they might just pull a rabbit out of a hat, or rather a rich new colony out of a mitre. Diplomatic negotiations between Portugal and Spain began in April. Meanwhile, the Pope got to work busily on crafting a new bull. Inter Caetera was issued on May 4, 1493, superseding three edicts issued that same day and the day before. Dudum Siquidem, which resolved some of the issues Inter Caetera had left open, was issued September 26th, 1493.

All of this was going down while Pinturicchio and his assistants lavishly frescoed the Pope’s apartment. Resurrection was painted on the wall of the Hall of Mysteries, one of three rooms in the apartment that were Alexander VI’s personal living space. The pope himself is portrayed prominently in the painting, on his knees, hands joined in prayer, before Christ’s resurrected golden glory. Considering how the Pope spent a great deal of 1493 dealing with the ramifications of Columbus’ discovery, and how all these political issues were framed in terms of who should get to convert the newly-found pagans to Christianity, it makes sense that they would make a cameo in this fresco.

After Alexander VI’s death in 1503, the apartment was closed by his successor Pope Pius III. Neither he nor anyone else for a few centuries wanted to be associated with the scandalous Borgia papacy, so the rooms with their gorgeous frescoes were sealed off for almost 400 years. Pope Leo XII finally opened them in 1889. Their years of disuse had kept the rooms in good condition and kept subsequent popes with bad taste from messing with the frescoes. The rooms are now part of the Vatican Library. Since 1973, they’ve housed the Vatican Collection of Modern Religious Art, a collection of more than 600 donated works by the likes of Chagall, Kandinsky and Gaugin.