The summer of 1813 was a tense time in Baltimore. The United States was at war with Britain and the city was poised for an invasion from land and sea. Fort McHenry, the star-shaped fort defending Baltimore Harbor, needed one last thing to be fully prepared for the British attack: a proper flag. Major George Armistead sought to remedy this oversight as soon as he took over as commander of the Fort McHenry militia detachment in June of 1813. He wrote to General Samuel Smith, commander of Baltimore:

“We, sir, are ready at Fort McHenry to defend Baltimore against invading by the enemy. That is to say, we are ready except that we have no suitable ensign to display over the Star Fort and it is my desire to have a flag so large that the British will have no difficulty seeing it from a distance.”

He was not kidding. Armistead commissioned Mary Pickersgill, a local flag maker with a well-established business making flags and signals for military and merchant ships (she also happened to be the sister-in-law of Commodore Joshua Barney, commander of the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla) to make two flags. One was a 17 x 25-foot storm flag that could tolerate inclement weather, and the other a whopping 30 x 42-foot garrison flag to be made of top quality woolen bunting. This was a huge job and Pickersgill had a very short deadline since Armistead wanted the flags ready to go as soon as possible. She enlisted the aid of her 13-year-old daughter Caroline, her nieces Eliza and Margaret Young, then just 13 and 15 respectively, Grace Wisher, an African-American apprentice, and possibly Pickersgill’s mother, Rebecca Young, herself an accomplished flagmaker who was one of the first on record to make flags for the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War and who had taught her daughter the craft.

He was not kidding. Armistead commissioned Mary Pickersgill, a local flag maker with a well-established business making flags and signals for military and merchant ships (she also happened to be the sister-in-law of Commodore Joshua Barney, commander of the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla) to make two flags. One was a 17 x 25-foot storm flag that could tolerate inclement weather, and the other a whopping 30 x 42-foot garrison flag to be made of top quality woolen bunting. This was a huge job and Pickersgill had a very short deadline since Armistead wanted the flags ready to go as soon as possible. She enlisted the aid of her 13-year-old daughter Caroline, her nieces Eliza and Margaret Young, then just 13 and 15 respectively, Grace Wisher, an African-American apprentice, and possibly Pickersgill’s mother, Rebecca Young, herself an accomplished flagmaker who was one of the first on record to make flags for the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War and who had taught her daughter the craft.

Pickersgill’s team worked relentlessly for six weeks making the flags. During preparations for the 1876 Centennial, Caroline wrote a letter to Georgiana Armistead Appleton, daughter of Major George Armistead and owner of the flag, describing their efforts:

“The flag being so very large, mother was obliged to obtain permission from the proprietors of Claggetts brewery which was in our neighborhood, to spread it out in their malt house; and I remember seeing my mother down on the floor, placing the stars: after the completion of the flag, she superintended the topping of it, having it fastened in the most secure manner to prevent its being torn away by (cannon) balls: the wisdom of her precaution was shown during the engagement: many shots piercing it, but it still remained firm to the staff. Your father (Col. Armistead) declared that no one but the maker of the flag should mend it, and requested that the rents should merely be bound around. The flag contained, I think, four hundred yards of bunting, and my mother worked many nights until 12 o’clock to complete it in the given time.”

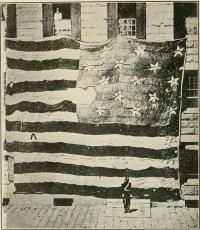

It was an exceptional piece of work, hand-sewing such a massive flag by stitching together strips of wool (for the blue canton and white and red stripes; the stars are cotton) no more than 18 inches wide. It was at that time, and I believe still is, the largest battle flag ever made. It weighed 50 pounds and required 11 men to hoist.

It was an exceptional piece of work, hand-sewing such a massive flag by stitching together strips of wool (for the blue canton and white and red stripes; the stars are cotton) no more than 18 inches wide. It was at that time, and I believe still is, the largest battle flag ever made. It weighed 50 pounds and required 11 men to hoist.

The finished product was delivered to Fort McHenry on August 19, 1813. The urgency of construction turned out to be unnecessary. Britain had its hands full at the time with a certain upstart French fellow, so the expected battle only happened more than a year later after Napoleon’s abdication on April 6th, 1814. When the British finally did shell Fort McHenry in the Battle of Baltimore the night of September 13-14th, 1814, they most certainly could see the garrison flag withstand the punishing assault, just as Armistead had wanted.

Lawyer and amateur poet Francis Scott Key was negotiating prisoner exchanges aboard the British ship HMS Tonnant in Baltimore Harbor during the British attack. They wouldn’t let him leave the ship lest he reveal their position until the shelling was done, so he spent the night and awoke to find Pickersgill’s giant flag was still there. He immortalized that sight in a poem called Defence of Fort McHenry (pdf) which would be set to a British drinking song and become the national anthem as The Star Spangled Banner.

This summer marks the 200th anniversary of the creation of the Fort McHenry garrison flag and the Maryland Historical Society has a plan to celebrate it in grand style. Starting the Fourth of July, more than 150 volunteers are coming together to hand-stitch an exact replica of the Star Spangled Banner in the same six-week time frame as the original. (It’s a testament to the skill and speed of Mary Pickersgill’s team that it takes 150 adults to accomplish today what she did with three teenagers and a couple of assistants.) The first stitch will be stitched in a ceremony at Fort McHenry after which visitors will be able to see the team hard at work in the Fort McHenry Education Center until 4:00 PM.

This summer marks the 200th anniversary of the creation of the Fort McHenry garrison flag and the Maryland Historical Society has a plan to celebrate it in grand style. Starting the Fourth of July, more than 150 volunteers are coming together to hand-stitch an exact replica of the Star Spangled Banner in the same six-week time frame as the original. (It’s a testament to the skill and speed of Mary Pickersgill’s team that it takes 150 adults to accomplish today what she did with three teenagers and a couple of assistants.) The first stitch will be stitched in a ceremony at Fort McHenry after which visitors will be able to see the team hard at work in the Fort McHenry Education Center until 4:00 PM.

The original is in the Smithsonian in an extremely delicate state of conservation. It will be great to have a hardy replica so the massive beastflag can yet wave. This is not a cheap project — the 275 yards of wool bunting alone cost $9,625 — and the Maryland Historical Society could use some help defraying costs. They’ve created a Kickstarter project with a goal of raising $10,000 by the end of the month. They’ve raised just over a thousand dollars over the past few days so donate and spread the word.

The Kickstarter has a lot of nerdy perks for donors, but the best of all perks is free. If you’re in Maryland on August 3rd or August 11th, go to the Maryland Historical Society’s workroom in France Hall between noon and 3:00 PM to put your own stitch in the flag.