Conservators restoring the late 13th/early 14th century square tower of Drum Castle 10 miles from Aberdeen, Scotland, have discovered two hidden chambers not documented on the plans of the castle. One is a garderobe, a toilet with its stone seat still intact. The other is a double chamber, two rooms connected by a doorway.

Conservators restoring the late 13th/early 14th century square tower of Drum Castle 10 miles from Aberdeen, Scotland, have discovered two hidden chambers not documented on the plans of the castle. One is a garderobe, a toilet with its stone seat still intact. The other is a double chamber, two rooms connected by a doorway.

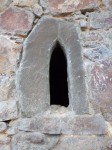

The chambers were not visible on the inside because they had been walled up during the construction of a library in the medieval keep during the 1840s. There are windows that can be seen from the outside, however, so the conservation team knew there was something between the outer wall and the Victorian library. It could have just been rubble filling an old passage, but since everyone wants to know what’s hidden behind castle walls, Dr. Jonathan Clark of FAS Heritage unblocked the three windows so he could look in from the outside.

Lit solely by a flashlight, the garderobe and its instantly recognizable toilet first greeted his eyes. Then he saw the entrance doorway, long since sealed up by wooden slats with mortar spilling through them. Two of the unblocked windows looked in on this toilet chamber. The third window looked in on second chamber of notable size. Dr. Clark took pictures of the chambers to document them as best he could, and I have to take a moment to slow clap the skills because any photographs I attempted to take by snaking a digital camera through a window slit in a massive medieval wall would come out looking hopelessly drunk. Hell, I’ve seen formal auction pictures that were blurry and poorly framed. My working theory is that Dr. Jonathan Clark has a bionic arm.

Lit solely by a flashlight, the garderobe and its instantly recognizable toilet first greeted his eyes. Then he saw the entrance doorway, long since sealed up by wooden slats with mortar spilling through them. Two of the unblocked windows looked in on this toilet chamber. The third window looked in on second chamber of notable size. Dr. Clark took pictures of the chambers to document them as best he could, and I have to take a moment to slow clap the skills because any photographs I attempted to take by snaking a digital camera through a window slit in a massive medieval wall would come out looking hopelessly drunk. Hell, I’ve seen formal auction pictures that were blurry and poorly framed. My working theory is that Dr. Jonathan Clark has a bionic arm.

In the first flush of excitement, speculation was rife that this might be the secret room in which Alexander Irvine, 17th laird of Drum and committed Jacobite, was hidden by his sister Mary after he fought for Bonnie Prince Charlie on the losing side of the Battle of Culloden (April 16th, 1746). Legend has it that she secreted him away in the keep while the loyalist troops of Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, son of King George II, ransacked the castle. Could this be the very room in which Alexander hid from the Redcoats?

In the first flush of excitement, speculation was rife that this might be the secret room in which Alexander Irvine, 17th laird of Drum and committed Jacobite, was hidden by his sister Mary after he fought for Bonnie Prince Charlie on the losing side of the Battle of Culloden (April 16th, 1746). Legend has it that she secreted him away in the keep while the loyalist troops of Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, son of King George II, ransacked the castle. Could this be the very room in which Alexander hid from the Redcoats?

No, it could not be. These chambers weren’t hidden in the 18th century. They were just part of the keep. On Friday conservators sent a remote video camera through the windows and discovered that the one large chamber actually has an adjoining second chamber. They weren’t able to explore it so all they could see was the throughway, but the location of this double chamber strongly suggests a far more pedestrian use as a butchery and pantry. It’s on the end of the lower hall against a north-facing wall. This would be the coldest place in the building where it makes little sense to have living spaces but a great deal of sense to have a food preparation and preservation area.

No, it could not be. These chambers weren’t hidden in the 18th century. They were just part of the keep. On Friday conservators sent a remote video camera through the windows and discovered that the one large chamber actually has an adjoining second chamber. They weren’t able to explore it so all they could see was the throughway, but the location of this double chamber strongly suggests a far more pedestrian use as a butchery and pantry. It’s on the end of the lower hall against a north-facing wall. This would be the coldest place in the building where it makes little sense to have living spaces but a great deal of sense to have a food preparation and preservation area.

Since conservators have no other way to explore the chambers, we don’t know if there are any artifacts left inside. The space is too dark for eyeball examination and too large for their cameras to explore thoroughly. On Tuesday, a camera crew from local television station STV news threaded a specialized extending camera through the windows to investigate the double chamber. The segment hasn’t aired yet so keep an eye on the website.

Since conservators have no other way to explore the chambers, we don’t know if there are any artifacts left inside. The space is too dark for eyeball examination and too large for their cameras to explore thoroughly. On Tuesday, a camera crew from local television station STV news threaded a specialized extending camera through the windows to investigate the double chamber. The segment hasn’t aired yet so keep an eye on the website.

Even though these aren’t secret castle chambers in the Gothic romance sense, finding a garderobe, butchery and pantry from the earliest days of Drum Castle is exciting. Drum’s keep is the oldest in Scotland, probably built by Richard Cementarius (Richard the Mason), architect and Provost of Aberdeen, by order of King Alexander III around 1280. It’s next to the Royal Forest of Drum where the kings of Scotland hunted for generations, so it may have been a powerfully reinforced hunting lodge of sorts. In 1323, Robert the Bruce gave the Barony of Drum and its castle to his friend, neighbor, armour-bearer and secretary William de Irwin in recognition of his 20 years of service.

For centuries Drum Castle was the seat of Clan Irvine. A mansion was added to the keep in the 17th century. The old tower was integrated into the new construction and appears to have been occupied for some time after the Jacobean mansion was built, but documentary evidence indicates that by the 18th century the keep was no longer in regular use. The tower was refurbished by the Victorian Irvines. This is when our medieval toilet and pantries were walled up and floor-to-ceiling bookshelves installed for the new library on the lower floor. The top floor was transformed into a dovecote.

For centuries Drum Castle was the seat of Clan Irvine. A mansion was added to the keep in the 17th century. The old tower was integrated into the new construction and appears to have been occupied for some time after the Jacobean mansion was built, but documentary evidence indicates that by the 18th century the keep was no longer in regular use. The tower was refurbished by the Victorian Irvines. This is when our medieval toilet and pantries were walled up and floor-to-ceiling bookshelves installed for the new library on the lower floor. The top floor was transformed into a dovecote.

The castle remained in the Irvine family from 1323 until 1975 when it was ceded to the National Trust for Scotland. The keep is the Trust’s oldest intact building. Conservators are working today to keep it intact. The plan is to remove all the cementatious mortars added over the years and replace them with lime mortars that match the mortar used in original construction. Dr. Clark notes that mixing materials in historical properties is never a good idea, and cement is particularly injurious to stone structure. Unlike lime mortar, cement doesn’t breathe so when moisture seeps in, it can’t escape through the mortar joints and has no way to get out except through the stone masonry itself. Then when winter strikes, all that damp freezes in the stonework, causing it to crack and crumble. The moisture trapped inside the building is also damaging the library and its extensive collection of books.

The castle remained in the Irvine family from 1323 until 1975 when it was ceded to the National Trust for Scotland. The keep is the Trust’s oldest intact building. Conservators are working today to keep it intact. The plan is to remove all the cementatious mortars added over the years and replace them with lime mortars that match the mortar used in original construction. Dr. Clark notes that mixing materials in historical properties is never a good idea, and cement is particularly injurious to stone structure. Unlike lime mortar, cement doesn’t breathe so when moisture seeps in, it can’t escape through the mortar joints and has no way to get out except through the stone masonry itself. Then when winter strikes, all that damp freezes in the stonework, causing it to crack and crumble. The moisture trapped inside the building is also damaging the library and its extensive collection of books.

Scaffolding went up in March and conservators hope to be finished with the project in September. So far everything is going according to schedule.