Researchers from Cambridge University and the University of Leicester have analyzed sediment samples collected in September of last year from the burial site of King Richard III and discovered that he suffered from intestinal parasites, namely roundworms. The samples were taken from three places: the sacral region of the pelvis at the base of his spine (marked S on the picture), the skull (C1) and a spot outside the grave’s edge (C2). The sacrum is a triangular bone that forms the back wall of the pelvic girdle. The intestines are contained in the pelvic girdle. Since obviously Richard’s intestines are long gone, any remains of their contents would be found in the sediment around the sacrum.

Researchers from Cambridge University and the University of Leicester have analyzed sediment samples collected in September of last year from the burial site of King Richard III and discovered that he suffered from intestinal parasites, namely roundworms. The samples were taken from three places: the sacral region of the pelvis at the base of his spine (marked S on the picture), the skull (C1) and a spot outside the grave’s edge (C2). The sacrum is a triangular bone that forms the back wall of the pelvic girdle. The intestines are contained in the pelvic girdle. Since obviously Richard’s intestines are long gone, any remains of their contents would be found in the sediment around the sacrum.

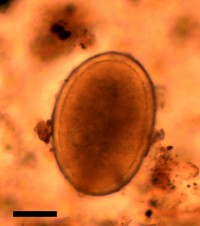

Analysis of the sacral sample found multiple eggs of the giant roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides) ranging from 55.1 to 69.8 micrometers in length. From those tiny eggs hatch the largest parasitic worm in humans. Adult females, which are bigger than the males, can reach over a foot in length. They are tremendously fertile, capable of laying 200,000 eggs every day. A person contracts a roundworm infection when they eat or drink something contaminated with egg-containing human feces. The eggs hatch in the small intestine and the larvae pass through its walls into the blood stream. From there they travel to the lungs where they grow for a few weeks until they’re coughed up and swallowed so they can head back home to the intestine. That’s where they grow to full size and sexual maturity and start producing hundreds of thousands of eggs a day so the cycle can start over again.

Roundworm eggs are remarkably resilient. They can remain viable in the soil for up to 10 years, and archaeological examples up to 24,000 years old have been found. Roundworm is the most common parasite in humans, infecting an estimated one sixth of the world. Improvements in sanitation in the US and Europe have drastically reduced the rates of roundworm infection making it relatively uncommon, but in Richard’s time it was widespread. Even kings weren’t spared, despite their access to the best food. All it took was an infected food handler with unwashed hands or vegetables grown using human feces as fertilizer, a common practice in the Middle Ages.

Roundworm eggs are remarkably resilient. They can remain viable in the soil for up to 10 years, and archaeological examples up to 24,000 years old have been found. Roundworm is the most common parasite in humans, infecting an estimated one sixth of the world. Improvements in sanitation in the US and Europe have drastically reduced the rates of roundworm infection making it relatively uncommon, but in Richard’s time it was widespread. Even kings weren’t spared, despite their access to the best food. All it took was an infected food handler with unwashed hands or vegetables grown using human feces as fertilizer, a common practice in the Middle Ages.

His cooks deserve credit for keeping other parasites at bay, though.

No other species of intestinal parasite were present in the samples. Past research into human intestinal parasites in Britain has shown several species to have been present prior to the medieval period, including roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides), whipworm (Trichuris trichiura), beef/pork tapeworm (Taenia saginata/solium), fish tapeworm (Diphyllobothrium latum), and liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica). We would expect nobles of this period to have eaten meats such as beef, pork, and fish regularly, but there was no evidence for the eggs of the beef, pork, or fish tapeworm. This finding might suggest that his food was cooked thoroughly, which would have prevented the transmission of these parasites.

We know the eggs in sacral sample weren’t the result of later contamination of the soil because the control sample taken from the skull area had no eggs present and the control sample from the edge of the pit had 15 times fewer eggs than the pelvic sediment sample. This is the first time the remains of a British king have been examined for intestinal parasites. If Richard had any idea he was infected — he could easily have been asymptomatic — treatment at the time would have involved bloodletting and medicines to counter specific symptoms like coughing, fever, bloody sputum and abdominal pain.

To close on the grossest note possible, here’s a thought from the AP article about this discovery:

It’s also possible Richard’s worms made a gruesome appearance when he died on the battlefield in 1485 as the last English king killed in war. In adults infected with roundworm, traumatic events like car crashes can cause the worms to pop out of peoples’ noses and ears.

“The worms get shocked and they move quickly,” said Simon Brooker, a professor of epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who was not part of the study. He said it was possible the many blade injuries suffered by Richard before his death could have prompted the worms in his body to make a hasty exit.