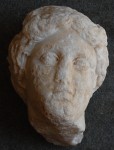

The dramatic 1600-square-foot Roman mosaic discovered last year in the ancient town of Antiochia ad Cragum on the southern coast of Turkey continues to bear fruit. Archaeologists excavating the part of the mosaic that was left underground at the end of the last digging season found a life-sized marble head of Aphrodite face down in the soil. The head has been damaged — there are copious chips on the nose, right eye, cheek and chin — and no matching body was found.

The dramatic 1600-square-foot Roman mosaic discovered last year in the ancient town of Antiochia ad Cragum on the southern coast of Turkey continues to bear fruit. Archaeologists excavating the part of the mosaic that was left underground at the end of the last digging season found a life-sized marble head of Aphrodite face down in the soil. The head has been damaged — there are copious chips on the nose, right eye, cheek and chin — and no matching body was found.

This one beaten up head is of disproportionate historical importance because it’s the only piece of monumental sculpture unearthed in eights years of excavations.

The new discoveries add evidence that early residents of Antiochia – which was established at about the time of Emperor Nero in the middle of the first century and flourished during the height of the Roman Empire – adopted many of the trappings of Roman civilization, though they lived in relative isolation a thousand miles from Rome. In the past, scholars believed the region’s culture had been too insular to be heavily impacted by Rome.

Yet [University of Nebraska–Lincoln professor of art history Michael] Hoff and his team have found many signs that contradict that belief.

“We have niches where statues once were. We just didn’t have any statues,” Hoff said. “Finally, we have the head of a statue. It suggests something of how mainstream these people were who were living here, how much they were a part of the overall Greek and Roman traditions.”

Lime kilns have been found near the site which suggests the statuary that once inhabited the niches of Antiochia ad Cragum were burned to make the slaked lime used in concrete. The rise of Christianity in the area in the 4th century may have also played a part as pagan iconography, including statues and figural reliefs, was a particular target of destruction.

Lime kilns have been found near the site which suggests the statuary that once inhabited the niches of Antiochia ad Cragum were burned to make the slaked lime used in concrete. The rise of Christianity in the area in the 4th century may have also played a part as pagan iconography, including statues and figural reliefs, was a particular target of destruction.

The head of Aphrodite wasn’t the only exceptional discovery this season. The team excavated the western half of the large mosaic surrounding the marble-lined swimming pool that was partially unearthed last year. They cleared the pool and found two stairways leading into it and benches along the inner sides. They also found that the elaborate mosaic floor was used as a base for a glass-blowing furnace in the middle of the fourth century, around the same time the lime kilns were in use. Because of these later finds, the date of the mosaic has been moved forward to the late second or early third century.

As if that weren’t enough for three month’s work, the archaeological team also discovered a second mosaic just south of the pool. They excavated a mound where toppled columns were visible above ground and found a square mosaic floor of geometric designs, fruits and flowers. The layout of the remains suggests this structure was a Roman temple which makes the floor even more unusual a find because mosaics floors are rare in Roman temples.

As if that weren’t enough for three month’s work, the archaeological team also discovered a second mosaic just south of the pool. They excavated a mound where toppled columns were visible above ground and found a square mosaic floor of geometric designs, fruits and flowers. The layout of the remains suggests this structure was a Roman temple which makes the floor even more unusual a find because mosaics floors are rare in Roman temples.

“Everything about it is telling us it’s a temple, but we don’t have much in the way of to whom it was dedicated,” he said. “We’re still analyzing the finds. But the architecture suggests heavily that it was a temple.”

While the larger bath plaza mosaic features large patterned areas, the temple mosaic uses smaller tesserae to compose geometric designs, as well as images of fruit and floral images amidst a chain guilloche of interlocking circles. The temple mosaic measures about 600 square feet.

Both mosaics will eventually be conserved and protected so visitors can enjoy their beauty in situ. For now, conservators repaired some of the damaged areas with a dedicated mortar then covered the mosaics with a conservation blanket and a heavy layer of sand to keep them safe from the elements and looters.