On Monday, October 29th, 2012, a mighty oak in the New Haven Green was toppled by Hurricane Sandy. Planted in 1909 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Abraham Lincoln, the oak tree was knocked down by the force of the winds and the large root ball fully exposed. Passerby Katie Carbo saw an oddly shaped rock embedded in the roots but when she looked closely, she found that weird rock was actually a human skull. She notified the police who brought in Alfredo Camargo, a death investigator from the state medical examiner’s office, to collect the human remains for examination.

On Monday, October 29th, 2012, a mighty oak in the New Haven Green was toppled by Hurricane Sandy. Planted in 1909 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Abraham Lincoln, the oak tree was knocked down by the force of the winds and the large root ball fully exposed. Passerby Katie Carbo saw an oddly shaped rock embedded in the roots but when she looked closely, she found that weird rock was actually a human skull. She notified the police who brought in Alfredo Camargo, a death investigator from the state medical examiner’s office, to collect the human remains for examination.

No foul play was suspected. The Green had been used as a cemetery from early colonial times through the dawn of the Federal era so it seemed likely the remains were historical. In fact, Yale anthropologist Gary Aronsen, State Archaeologist Nick Bellantoni and archaeologist Dan Forrest worked with Camargo to collect the bones and any artifacts that might help date or identify the remains. A hand-wrought iron coffin nail from the late 18th century suggested a preliminary date, but a confirmation would require further analysis of the bones.

It was a ghoulish surprise well-suited for Halloween to many New Havenites who had long forgotten that their central green was once a very active cemetery. The Puritans began burying people in the square pretty much as soon as they arrived in 1638, a party of 500 led by Reverend John Davenport and Theophilus Eaton who had left the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the wake of the great Antinomian Controversy, a debate about whether salvation comes through good works or solely by the grace of God that ended with the excommunication of Free Grace advocate Anne Hutchinson. Massachusetts Bay Governor John Winthrop, who had delivered the famous “City upon a Hill” sermon to the colonists while they were still on the ship, sided with the works people and his autocratic style of governance had already alienated the likes of Roger Williams, founder of Rhode Island. Davenport was more of a salvation through grace fellow, so he and Eaton founded New Haven to get out from under Winthrop’s thumb and to worship as they preferred.

It was a ghoulish surprise well-suited for Halloween to many New Havenites who had long forgotten that their central green was once a very active cemetery. The Puritans began burying people in the square pretty much as soon as they arrived in 1638, a party of 500 led by Reverend John Davenport and Theophilus Eaton who had left the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the wake of the great Antinomian Controversy, a debate about whether salvation comes through good works or solely by the grace of God that ended with the excommunication of Free Grace advocate Anne Hutchinson. Massachusetts Bay Governor John Winthrop, who had delivered the famous “City upon a Hill” sermon to the colonists while they were still on the ship, sided with the works people and his autocratic style of governance had already alienated the likes of Roger Williams, founder of Rhode Island. Davenport was more of a salvation through grace fellow, so he and Eaton founded New Haven to get out from under Winthrop’s thumb and to worship as they preferred.

The town green was one of the first things they built. It was designed specifically so it would be the proper size to accommodate 144,000 people, the number they believed would be saved in the Second Coming. What better place to inter the dead than underneath the future launching pad of the Rapture? Burials began in 1638 and continued undiminished through 1797. By then the small space was just heaving with bodies. New dead were buried on top of previous burials and most graves went unmarked. An estimate 5,000 – 10,000 people were laid to rest under the New Haven Green.

Finally after a series of epidemics — scarlet fever, yellow fever, dysentery — in the 1790s forced the burial of as many as 5,000 victims within two years, it became palpably clear that New Haven needed a new burial ground. The Grove Street Cemetery was built on the edge of the city limits in 1797. This was the first chartered burial ground in the United States. In 1821, the remaining headstones from the Green were carried to the new cemetery by a procession of Yale students where they were arranged against the north and west walls in alphabetical order.

There were still occasional burials in the Green until 1812 when a new church was built over a section of the Green. Center Church simply absorbed the piece of the burial ground it was built over, keeping the burials and headstones in place in a basement crypt. The crypt holds 137 burials marked with headstones and other monuments and an estimate 1,000 unmarked graves. There are some historically significant personages among those 137: Margaret Arnold, the first wife of Benedict Arnold, Ezekiel Hayes, Revolutionary War hero and great-grandfather of President Rutherford B. Hayes, New Haven co-founder and colony governor Theophilus Eaton, and Reverend James Pierpont, a founder of Yale College whose daughter Sarah married Jonathan Edwards, Great Awakening preacher of “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” the sermon that scared the crap out of me when I read it in 8th grade English class, and had 11 children whose direct descendants include Vice President and infamous dueler Aaron Burr, financier John Pierpont Morgan and such a vast network of intellectuals, university presidents, captains of industry and political leaders that eugenicists in the early 1900s pointed to the extended Edwards’ family as an example of what good breeding can accomplish.

There were still occasional burials in the Green until 1812 when a new church was built over a section of the Green. Center Church simply absorbed the piece of the burial ground it was built over, keeping the burials and headstones in place in a basement crypt. The crypt holds 137 burials marked with headstones and other monuments and an estimate 1,000 unmarked graves. There are some historically significant personages among those 137: Margaret Arnold, the first wife of Benedict Arnold, Ezekiel Hayes, Revolutionary War hero and great-grandfather of President Rutherford B. Hayes, New Haven co-founder and colony governor Theophilus Eaton, and Reverend James Pierpont, a founder of Yale College whose daughter Sarah married Jonathan Edwards, Great Awakening preacher of “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” the sermon that scared the crap out of me when I read it in 8th grade English class, and had 11 children whose direct descendants include Vice President and infamous dueler Aaron Burr, financier John Pierpont Morgan and such a vast network of intellectuals, university presidents, captains of industry and political leaders that eugenicists in the early 1900s pointed to the extended Edwards’ family as an example of what good breeding can accomplish.

Despite this rich history writ in the bones of the New Haven Green, general memory of the burials faded over time. When the Lincoln Oak was planted in 1909, there was no mention of the site as a former burial ground. The spot was chosen for the planting because the Connecticut State House had stood on the site from 1828 to 1889 and that’s where the public prayers were said after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth.

Despite this rich history writ in the bones of the New Haven Green, general memory of the burials faded over time. When the Lincoln Oak was planted in 1909, there was no mention of the site as a former burial ground. The spot was chosen for the planting because the Connecticut State House had stood on the site from 1828 to 1889 and that’s where the public prayers were said after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth.

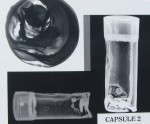

The Lincoln Oak’s skeletal roots brought it all back, and not for the first time either. Believe it or not, Hurricane Esther partially toppled the oak on September 27th, 1961, exposing the roots and, yes, a handful of human bones entangled in them (pdf). New Haveners were as surprised then as they would be 51 years later, which goes to show our memories are ridiculously short even in the age of mass media. There are plenty of people still around who were there in 1961, but it took local historian Rob Greenberg digging through the archives of the New Haven Register to bring the earlier episode to light. Rob Greenberg also doggedly pursued the mystery of a concrete cylinder found under the oak’s 1909 plaque which turned out to contain two time capsules with Civil War and Lincoln mementos that was buried when the oak was planted.

mystery of a concrete cylinder found under the oak’s 1909 plaque which turned out to contain two time capsules with Civil War and Lincoln mementos that was buried when the oak was planted.

Basically this Lincoln Oak was like the kite-eating tree in Peanuts only with bones instead of kites, and it’s the roots that do all the entrapping rather than the branches. Once it was replanted in 1961, the roots just kept growing until they found more bones to nom. Sadly, the tree could not take root once more after Sandy. This fall was its last. A new oak was planted on the spot, however, so the whole thing can happen again a century from now.

As for the bones plucked out of its roots last year, the first official report of the findings will be made tonight at a panel discussion at the New Haven Museum. The event starts at 5:30 PM, is scheduled to run just over two hours and is open to the public. Analysis did confirm that the evidence of the coffin nail was accurate: the bones date to the late 1790s. There are bones from at least four people in this group: one adult male, one child of 7-9 and two younger children. The adult was buried in a decorated casket, fragments of which survive. One of the children was buried with a red marble toy. There were signs on the teeth of early childhood malnutrition but no cause of death could be determined for any of the four.

Here’s a Yale News video with good shots of the uprooted tree and bones:

[youtube=http://youtu.be/Jq6CtOAP-6M&w=430]

The remains will be reinterred when research is complete. No word yet on where they’ll be buried.