Happy 43rd birthday, Tom Carroll! This one’s for you.

Caesar Augustus, adopted son and heir of Julius Caesar and first emperor of Rome, died on August 19th, 14 A.D., 57 years to the day after he was first “elected” consul of Rome. (He showed up at the city gates with eight legions, so it wasn’t much of an election.) According to Cassius Dio (Roman History, Book LVI, Chapter 30), on his deathbed Augustus declared: “I found Rome of clay; I leave it to you of marble.” Suetonius agrees, noting in The Lives of the Twelve Caesars that “since the city was not adorned as the dignity of the empire demanded, and was exposed to flood and fire, he so beautified it that he could justly boast that he had found it built of brick and left it in marble.”

Caesar Augustus, adopted son and heir of Julius Caesar and first emperor of Rome, died on August 19th, 14 A.D., 57 years to the day after he was first “elected” consul of Rome. (He showed up at the city gates with eight legions, so it wasn’t much of an election.) According to Cassius Dio (Roman History, Book LVI, Chapter 30), on his deathbed Augustus declared: “I found Rome of clay; I leave it to you of marble.” Suetonius agrees, noting in The Lives of the Twelve Caesars that “since the city was not adorned as the dignity of the empire demanded, and was exposed to flood and fire, he so beautified it that he could justly boast that he had found it built of brick and left it in marble.”

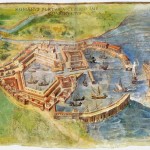

The first of Augustus’ many marble-clad improvements to the city of Rome was a monumental tomb for himself and his family. Construction began upon his return from Egypt in 31 B.C. after the final defeat of Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium. With Antony dead by his own hand and Lepidus exiled, Augustus was the last triumvir standing and the sole ruler of Rome. While in Egypt, Augustus had visited the tomb of Alexander the Great in Alexandria, leaving flowers and placing a golden diadem on Alexander’s head. The grand Hellenistic mausoleum inspired the Augustus’ version built on the Campus Martius in Rome.

The tomb was completed in 28 B.C. Here’s Strabo’s description of it in Geography, Book V, Chapter 3:

The most noteworthy [among the great tombs on the Campus Martius] is what is called the Mausoleum, a great mound near the river on a lofty foundation of white marble, thickly covered with ever-green trees to the very summit. Now on top is a bronze image of Augustus Caesar; beneath the mound are the tombs of himself and his kinsmen and intimates; behind the mound is a large sacred precinct with wonderful promenades; and in the centre of the Campus is the wall (this too of white marble) round his crematorium; the wall is surrounded by a circular iron fence and the space within the wall is planted with black poplars.

The most noteworthy [among the great tombs on the Campus Martius] is what is called the Mausoleum, a great mound near the river on a lofty foundation of white marble, thickly covered with ever-green trees to the very summit. Now on top is a bronze image of Augustus Caesar; beneath the mound are the tombs of himself and his kinsmen and intimates; behind the mound is a large sacred precinct with wonderful promenades; and in the centre of the Campus is the wall (this too of white marble) round his crematorium; the wall is surrounded by a circular iron fence and the space within the wall is planted with black poplars.

The circular walls of the tomb were made of brick and clad in white marble or travertine. The roof was supported by vaults which left the inside sectioned for family burials. The entry arch was framed on either side with red granite obelisks pillaged from Egypt. The finished Mausoleum was 295 feet in diameter and an estimated 137 feet high (not counting the height of the cypress trees).

The first to be buried in the Mausoleum was Marcellus, Augustus’ nephew, who died in 23 B.C. The ashes of Augustus’ mother Atia Balba, who had died in 43 B.C., were moved to the family tomb at the same time. Next was Augustus’ greatest general and son-in-law Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa in 12 B.C. Three years later was the turn of Nero Claudius Drusus, Augustus’ stepson. His sister Octavia also died and was buried around that time (her exact year of death is unknown, either 11 or 9 B.C.). The sons of Agrippa and Augustus’ daughter Julia were next, Lucius in 2 A.D., Gaius in 4 A.D. Augustus himself followed Gaius 10 years later.

After Augustus’ death, his wife Livia followed, then Germanicus, Agrippina the Elder, Agrippina’s daughter Livilla, Germanicus’ sons Nero and Drusus Caesar, Caligula, Tiberius, Tiberius’ son Drusus Julius Caesar, Claudius’ parents Nero Claudius Drusus and Antonia, then Claudius, his son Britannicus and Nero’s wife Poppaea Sabina (whose body was embalmed rather than cremated). The last emperor to join the illustrious crowd in the Mausoleum was Nerva, who died in 98 A.D.

After Augustus’ death, his wife Livia followed, then Germanicus, Agrippina the Elder, Agrippina’s daughter Livilla, Germanicus’ sons Nero and Drusus Caesar, Caligula, Tiberius, Tiberius’ son Drusus Julius Caesar, Claudius’ parents Nero Claudius Drusus and Antonia, then Claudius, his son Britannicus and Nero’s wife Poppaea Sabina (whose body was embalmed rather than cremated). The last emperor to join the illustrious crowd in the Mausoleum was Nerva, who died in 98 A.D.

Basically, the entire cast of I, Claudius wound up in the Mausoleum. The only exceptions were the exiled and disgraced Julio-Claudians, like Augustus’ only daughter Julia who died shortly after her father and was explicitly prohibited from being buried with her dad by the terms of his will. Her daughter Julia suffered the same fate. The Emperor Nero, last of the Julio-Claudian line, was buried with his paternal family in the Mausoleum of the Domitii Ahenobarbi.

The monument remained one of the most important ones in Rome until it was pillaged by the Visigoths in the 5th century. After that, like so many of its brethren it was used as a source of construction materials by Romans. The pink granite obelisks were toppled and buried. The first was rediscovered in the 16th century by Pope Sixtus V who moved it to the Piazza dell’Esquilino where it flanks the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore. The other was rediscovered in the 18th century and moved to the fountain between the equestrian statues of the Dioscuri on the Quirinal hill.

The monument remained one of the most important ones in Rome until it was pillaged by the Visigoths in the 5th century. After that, like so many of its brethren it was used as a source of construction materials by Romans. The pink granite obelisks were toppled and buried. The first was rediscovered in the 16th century by Pope Sixtus V who moved it to the Piazza dell’Esquilino where it flanks the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore. The other was rediscovered in the 18th century and moved to the fountain between the equestrian statues of the Dioscuri on the Quirinal hill.

And so Augustus’ legacy reverted from marble back to brick. As would later happen to the tomb of Hadrian, now the Castel Sant’Angelo, the Mausoleum of Augustus was converted into a fortress in the 12th century by the Colonna family. When they were defeated by the Counts of Tusculum in the Battle of Monte Porzio in 1167, the Mausoleum was stripped of its fortifications leaving it in ruin.

It still maintained its cachet to Romans, however. Cola di Rienzo, Tribune of the People, Senator of Rome, who briefly ruled the city over the howls of the Pope and endlessly bickering Roman nobility, was brutally killed in 1354 on my birthday, no less (well, 618 years before my birthday, but on the same day, is my point), and after his corpse was outraged for two days and a night, it was taken to the Mausoleum of Augustus and burned.

In 1519, Pope Leo X, son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, had what was left of the travertine cladding removed to use as paving stones for the Via Ripetta, the street that leads to the Mausoleum. Pope Paul III sold the Mausoleum in 1546 to Monsignor Francesco Soderini who excavated the site looking for ancient sculptures and then converted the Mausoleum into a sculpture garden with a hedge labyrinth that was popular with artists, classicists and antiquarians. The Soderini’s financial difficulties gradually saw the sculptures dispersed, although the Mausoleum remained a garden until 1780 when it was acquired by the Marquess Francesco Saverio Vivaldi-Armentieri. He turned it into an amphitheater with elegant boxes and seating for 1,000. There he staged bullfights and buffalo fights (of the water buffalo variety, not the American bison variety), operas, theatricals and on summer nights, fireworks displays at which all the noblewomen of Rome wore white dresses so the colors bursting in air would be reflected in their garments.

In 1519, Pope Leo X, son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, had what was left of the travertine cladding removed to use as paving stones for the Via Ripetta, the street that leads to the Mausoleum. Pope Paul III sold the Mausoleum in 1546 to Monsignor Francesco Soderini who excavated the site looking for ancient sculptures and then converted the Mausoleum into a sculpture garden with a hedge labyrinth that was popular with artists, classicists and antiquarians. The Soderini’s financial difficulties gradually saw the sculptures dispersed, although the Mausoleum remained a garden until 1780 when it was acquired by the Marquess Francesco Saverio Vivaldi-Armentieri. He turned it into an amphitheater with elegant boxes and seating for 1,000. There he staged bullfights and buffalo fights (of the water buffalo variety, not the American bison variety), operas, theatricals and on summer nights, fireworks displays at which all the noblewomen of Rome wore white dresses so the colors bursting in air would be reflected in their garments.

The amphitheater wasn’t very profitable and in 1802 the Pope Pius VII bought the Mausoleum back. It was still used for spectacles of various sorts — animal fights, balls, carnivals, circuses, lottery drawings, plays, equestrian displays, even a test of fire-retardant materials like that asbestos suit I mentioned in a recent entry. After the Unification of Italy, the Vatican sold the Mausoleum to the Count Telfener who put a roof on it and renamed it the Amphitheater Umberto I after the new King of Italy. It was used for plays, concerts and operas, no more buffalo fights.

The amphitheater wasn’t very profitable and in 1802 the Pope Pius VII bought the Mausoleum back. It was still used for spectacles of various sorts — animal fights, balls, carnivals, circuses, lottery drawings, plays, equestrian displays, even a test of fire-retardant materials like that asbestos suit I mentioned in a recent entry. After the Unification of Italy, the Vatican sold the Mausoleum to the Count Telfener who put a roof on it and renamed it the Amphitheater Umberto I after the new King of Italy. It was used for plays, concerts and operas, no more buffalo fights.

In 1909 it was refurbished yet again in Art Nouveau style and named the Augusteo in recognition of its original builder. Expanded to seat 3,500 people, the Augusteo was the seat of Rome’s main orchestra conducted by the great Arturo Toscanini, among others. Mussolini put an end to all that in 1936. He kicked out all the musicians, tore down the Renaissance buildings around it and ripped out all the theatrical modifications to return the Mausoleum to its original Roman masonry. This was a key part of his program of associating himself with the glory of ancient Rome and depicting himself as a second Augustus. Unfortunately, he did a piss-poor job of it. He had cypresses planted on top of the walls, in the mistaken belief that that’s where they had been placed originally instead of on the earthen tumulus. Inside the Mausoleum he had a squat two-storey tower built to mark the spot where Augustus’ ashes were once enshrined.

In 1909 it was refurbished yet again in Art Nouveau style and named the Augusteo in recognition of its original builder. Expanded to seat 3,500 people, the Augusteo was the seat of Rome’s main orchestra conducted by the great Arturo Toscanini, among others. Mussolini put an end to all that in 1936. He kicked out all the musicians, tore down the Renaissance buildings around it and ripped out all the theatrical modifications to return the Mausoleum to its original Roman masonry. This was a key part of his program of associating himself with the glory of ancient Rome and depicting himself as a second Augustus. Unfortunately, he did a piss-poor job of it. He had cypresses planted on top of the walls, in the mistaken belief that that’s where they had been placed originally instead of on the earthen tumulus. Inside the Mausoleum he had a squat two-storey tower built to mark the spot where Augustus’ ashes were once enshrined.

The end result of this brutal hack job was a Mausoleum in tatters, a derelict island in the middle of a traffic-engorged piazza. Homeless people found refuge under its walls and fences went up in a futile attempt to keep them out. Colonnaded Fascist buildings line the square while the real thing continues to decay. You can see its unfortunate current situation on Google Street View. Hadrian’s mausoleum, still clad in its medieval fortress trappings, is one of the icons of Rome, but Augustus’ tomb, which held the ashes of the first emperor and so many other august (*cough*) personages, doesn’t even make it onto postcards.

The end result of this brutal hack job was a Mausoleum in tatters, a derelict island in the middle of a traffic-engorged piazza. Homeless people found refuge under its walls and fences went up in a futile attempt to keep them out. Colonnaded Fascist buildings line the square while the real thing continues to decay. You can see its unfortunate current situation on Google Street View. Hadrian’s mausoleum, still clad in its medieval fortress trappings, is one of the icons of Rome, but Augustus’ tomb, which held the ashes of the first emperor and so many other august (*cough*) personages, doesn’t even make it onto postcards.

There was a plan to restore it in 2006 when the new glass enclosure of the Ara Pacis was built, but the funding never materialized, and the recession has starved Rome of the budget to maintain its ancient treasures.

Now Rome is reaching out to private donors to make up for its slashed budgets and it seems someone has stepped up to the plate for the Mausoleum of Augustus, one of the most expensive and difficult restorations in Rome. Mayor Ignazio Marino says a Saudi prince has approached him, expressing interest in funding the work. Who knows if that will come through, but meanwhile two million euros of public moneys have been allocated to get the process started. The mayor claims work will begin before the end of the year so that it will be in concert with the 2,000th anniversary of Augustus’ death.

The only known surviving copy of a classic 1927 Chinese silent film has returned home. The restored copy of Pan Si Dong (The Cave of the Silken Web) was handed over to the China Film Archive in Beijing on Tuesday. After the ceremony and a reception attended by invited guests, the film, accompanied live by Chinese pianist Jin Ye, was screened at a sold out show in front of an audience of 600.

The only known surviving copy of a classic 1927 Chinese silent film has returned home. The restored copy of Pan Si Dong (The Cave of the Silken Web) was handed over to the China Film Archive in Beijing on Tuesday. After the ceremony and a reception attended by invited guests, the film, accompanied live by Chinese pianist Jin Ye, was screened at a sold out show in front of an audience of 600.  The film was thought to be lost until a nitrate print from 1929 was discovered in the National Library of Norway. It was found in 2011 when the library decided to examine all 9,000 cans of film in its collection. At first they didn’t realize what a treasure they had. The film had no opening credits to easily identify it and it was too delicate for careful examination of the whole movie. After an initial cleaning, the nitrate film was sent to a laboratory where it was copied onto stock that does not spontaneously burst into flames. Library researchers then began to investigate the history of the movie. That’s when they discovered that they had the only existing copy in the world.

The film was thought to be lost until a nitrate print from 1929 was discovered in the National Library of Norway. It was found in 2011 when the library decided to examine all 9,000 cans of film in its collection. At first they didn’t realize what a treasure they had. The film had no opening credits to easily identify it and it was too delicate for careful examination of the whole movie. After an initial cleaning, the nitrate film was sent to a laboratory where it was copied onto stock that does not spontaneously burst into flames. Library researchers then began to investigate the history of the movie. That’s when they discovered that they had the only existing copy in the world. Pan Si Dong, directed by Dan Duyu for the Shanghai Shadow Play company, tells a story taken from Journey to the West, a 16th century book by Wu Cheng’en that is considered one of China’s four classic novels. The hero is Hiuen Tsiang Tang, a Buddist monk sent to the “Western regions,” ie, India, by Emperor T’ai Tsung to bring back sacred texts. Accompanied by three protectors — Monkey, Pigsy and Sandy — and riding a fourth companion, the Dragon prince, in the guise of white horse, the monk arrives at the spider valley where they find themselves in a cave where seven beautiful women live.

Pan Si Dong, directed by Dan Duyu for the Shanghai Shadow Play company, tells a story taken from Journey to the West, a 16th century book by Wu Cheng’en that is considered one of China’s four classic novels. The hero is Hiuen Tsiang Tang, a Buddist monk sent to the “Western regions,” ie, India, by Emperor T’ai Tsung to bring back sacred texts. Accompanied by three protectors — Monkey, Pigsy and Sandy — and riding a fourth companion, the Dragon prince, in the guise of white horse, the monk arrives at the spider valley where they find themselves in a cave where seven beautiful women live.  The women are actually spider spirits in disguise who want to devour the monk, believing this will make them immortal. They succeed in capturing the party, but then one of the spider spirits is busted trying to double-cross the rest so she and her demon lover can eat him on their own. In the ensuing battle, Xuanzang and his spirit compadres escape. The spider women and their webs are destroyed by purifying fire.

The women are actually spider spirits in disguise who want to devour the monk, believing this will make them immortal. They succeed in capturing the party, but then one of the spider spirits is busted trying to double-cross the rest so she and her demon lover can eat him on their own. In the ensuing battle, Xuanzang and his spirit compadres escape. The spider women and their webs are destroyed by purifying fire. The movie was hugely popular in China and a sequel was made in 1929. While the sequel was playing in China, the original made its way to Norway. Pan Si Dong was the first Chinese picture to be shown in Norway. It premiered in Oslo’s Chat Noir Cabaret Theater on January 18th, 1929, accompanied by the Colosseum orchestra. The print was customized for Norwegian audiences, with Norwegian translations appearing alongside the original Chinese on the title slides. The translation is not always accurate to the original. The translator interspersed his own comments in brackets next to some titles, and the Chinese is sometimes upside-down or backwards. This was noticed in some of the contemporary reviews which were generally positive, if patronizing. Norwegian reviewers found it “distinctive and interesting,” “quite strange,” and “worthwhile as a curiosity.”

The movie was hugely popular in China and a sequel was made in 1929. While the sequel was playing in China, the original made its way to Norway. Pan Si Dong was the first Chinese picture to be shown in Norway. It premiered in Oslo’s Chat Noir Cabaret Theater on January 18th, 1929, accompanied by the Colosseum orchestra. The print was customized for Norwegian audiences, with Norwegian translations appearing alongside the original Chinese on the title slides. The translation is not always accurate to the original. The translator interspersed his own comments in brackets next to some titles, and the Chinese is sometimes upside-down or backwards. This was noticed in some of the contemporary reviews which were generally positive, if patronizing. Norwegian reviewers found it “distinctive and interesting,” “quite strange,” and “worthwhile as a curiosity.” Side note of interest: one of the great things about silent movies is how universal they were. Movie theaters all over the world could easily created title cards in their language. There was no need for post-production translations of complex dialogue and dubbing. That means it really doesn’t matter where a lost silent picture is found, because the movie retains its integrity even when the title card translations are tonally questionable or inaccurate.

Side note of interest: one of the great things about silent movies is how universal they were. Movie theaters all over the world could easily created title cards in their language. There was no need for post-production translations of complex dialogue and dubbing. That means it really doesn’t matter where a lost silent picture is found, because the movie retains its integrity even when the title card translations are tonally questionable or inaccurate.