The University of Sheffield is returning an 18th century tapestry to the French château whence it was looted by Nazis during World War II. The University bought the 12-foot-high tapestry from an art dealer in 1959 for around £1,300, not realizing its ugly history, and put it on display in a meeting room in Firth Court which subsequently became known as The Tapestry Room. In 2013, they decided to sell the work. That’s when they found out that it was Nazi loot and began working with the Art Loss Register to trace its legitimate owner.

The University of Sheffield is returning an 18th century tapestry to the French château whence it was looted by Nazis during World War II. The University bought the 12-foot-high tapestry from an art dealer in 1959 for around £1,300, not realizing its ugly history, and put it on display in a meeting room in Firth Court which subsequently became known as The Tapestry Room. In 2013, they decided to sell the work. That’s when they found out that it was Nazi loot and began working with the Art Loss Register to trace its legitimate owner.

The tapestry was made around 1720 by the Beauvais Tapestry Manufacture, a privately owned workshop contracted by Jean-Baptiste Colbert, finance minister of Louis XIV, for royal production in the second half of the 17th century. It depicts a scene from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, one of a number of Beauvais tapestries to cover Ovid’s classic mythological tales.

This tapestry, along with two others still missing, was looted from the Château de Versainville in the northwestern province of Basse-Normandie in 1943 or 1944, at that time owned by the Comte Bernard de la Rochefoucauld. Bernard was the third son of the Comte Pierre de La Rochefoucauld, Duke of La Roche-Guyon. He was raised at Versainville and inherited the villa from his maternal grandmother in 1936. Dedicated to the management of his estate and deeply involved in the community, Bernard was mayor of the city of Versainville before the war. During the German occupation, he joined the Resistance and was part of the Prosper Network, a resistance network created and supported by the British Special Operations Executive. The Count was arrested by the Gestapo in Paris in the summer of 1943 and interned at Flossenbürg concentration camp in Bavaria. He died there on June 4th, 1944, when he was just 43 years old. His wife was also arrested and interned, but she survived until liberation and went on to live a very long life, dying in 1999 three weeks shy of her 97th birthday.

This tapestry, along with two others still missing, was looted from the Château de Versainville in the northwestern province of Basse-Normandie in 1943 or 1944, at that time owned by the Comte Bernard de la Rochefoucauld. Bernard was the third son of the Comte Pierre de La Rochefoucauld, Duke of La Roche-Guyon. He was raised at Versainville and inherited the villa from his maternal grandmother in 1936. Dedicated to the management of his estate and deeply involved in the community, Bernard was mayor of the city of Versainville before the war. During the German occupation, he joined the Resistance and was part of the Prosper Network, a resistance network created and supported by the British Special Operations Executive. The Count was arrested by the Gestapo in Paris in the summer of 1943 and interned at Flossenbürg concentration camp in Bavaria. He died there on June 4th, 1944, when he was just 43 years old. His wife was also arrested and interned, but she survived until liberation and went on to live a very long life, dying in 1999 three weeks shy of her 97th birthday.

After the war, the château was acquired by the Ford Motor Company for use as a summer camp for the children of its employees. It continued to be used as such until the late 1990s when it was sold to another car company, Peugeot Citroën. In 2002, the Château de Versainville was bought back for the family by the Comte Jacques de la Rochefoucauld, Bernard’s grand-nephew, who has worked hard to restore the property to its former splendor. The University of Sheffield’s return of one of the looted tapestries is a meaningful step towards this goal.

After the war, the château was acquired by the Ford Motor Company for use as a summer camp for the children of its employees. It continued to be used as such until the late 1990s when it was sold to another car company, Peugeot Citroën. In 2002, the Château de Versainville was bought back for the family by the Comte Jacques de la Rochefoucauld, Bernard’s grand-nephew, who has worked hard to restore the property to its former splendor. The University of Sheffield’s return of one of the looted tapestries is a meaningful step towards this goal.

In response to the donation of the tapestry, Comte Jacques de la Rochefoucauld commented that: “I am delighted by this news and touched by the generosity of the University of Sheffield in making so kind a gesture. The example that the University has set is one which I hope others will follow in due course, and demonstrates their respect for those who have suffered in the past from the ravages of war. In the year marking the 70th anniversary of the death of Comte Bernard de la Rochefoucauld this donation brings us great happiness.”

Comte Jacques plans to put the tapestry on display at Versainville with a plaque detailing its vicissitudes, including the 50 years it spent at Sheffield.

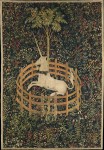

This isn’t the La Rochefoucauld family’s only encounter with tapestry looting. They once owned some of the most famous tapestries in the world: the seven Unicorn Tapestries that are now the greatest stars of the Metropolitan Museum’s medieval art branch, The Cloisters. The series was made between 1495 and 1505 and first appeared in the 1728 inventory of the La Rouchefoucauld family seat the Chateau La Roche-Guyon in northern France, although they may not have been originally made for the family (another candidate for the original commissioner of the tapestries is the inimitable Anne of Brittany). They were looted during the French Revolution and used to cover potatoes. The La Rochefoucauld family eventually got the Unicorn Tapestries back in the 1880s only to sell them 40 years later to John D. Rockefeller. He donated them to the Met in 1938.

This isn’t the La Rochefoucauld family’s only encounter with tapestry looting. They once owned some of the most famous tapestries in the world: the seven Unicorn Tapestries that are now the greatest stars of the Metropolitan Museum’s medieval art branch, The Cloisters. The series was made between 1495 and 1505 and first appeared in the 1728 inventory of the La Rouchefoucauld family seat the Chateau La Roche-Guyon in northern France, although they may not have been originally made for the family (another candidate for the original commissioner of the tapestries is the inimitable Anne of Brittany). They were looted during the French Revolution and used to cover potatoes. The La Rochefoucauld family eventually got the Unicorn Tapestries back in the 1880s only to sell them 40 years later to John D. Rockefeller. He donated them to the Met in 1938.