One of only 233 known copies of the First Folio edition of Shakespeare’s plays has been discovered in the library of Saint-Omer, a small town in northern France 30 miles south of Calais. Rémy Cordonnier, director of the medieval and early modern collection, found it this September when looking through the library’s stack for materials that would suit an upcoming English literature exhibition. Missing its telltale title page, the volume was wrongly classified as an 18th century edition, but Cordonnier suspected the missing pages might be making a secret identity as one of the rarest and most sought-after books in the world.

One of only 233 known copies of the First Folio edition of Shakespeare’s plays has been discovered in the library of Saint-Omer, a small town in northern France 30 miles south of Calais. Rémy Cordonnier, director of the medieval and early modern collection, found it this September when looking through the library’s stack for materials that would suit an upcoming English literature exhibition. Missing its telltale title page, the volume was wrongly classified as an 18th century edition, but Cordonnier suspected the missing pages might be making a secret identity as one of the rarest and most sought-after books in the world.

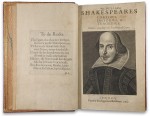

He contacted Eric Rasmussen from the University of Nevada, an expert on Shakespeare’s First Folio who spent 20 years cataloguing all known copies and who happened to be visiting the British Library. Last Saturday he took the Eurostar train to France too see the work in person. He authenticated it almost at first glance. The paper, its watermarks and certain errors that were corrected in later editions immediately identified it as the 233rd First Folio, the first new one discovered in a decade. Printed in 1623, just seven years after Shakespeare’s death, by his friends and fellow actors John Heminges and Henry Condell, the First Folio contains 36 of Shakespeare’s 38 plays, and is the earliest, most reliable extant source for half of them.

He contacted Eric Rasmussen from the University of Nevada, an expert on Shakespeare’s First Folio who spent 20 years cataloguing all known copies and who happened to be visiting the British Library. Last Saturday he took the Eurostar train to France too see the work in person. He authenticated it almost at first glance. The paper, its watermarks and certain errors that were corrected in later editions immediately identified it as the 233rd First Folio, the first new one discovered in a decade. Printed in 1623, just seven years after Shakespeare’s death, by his friends and fellow actors John Heminges and Henry Condell, the First Folio contains 36 of Shakespeare’s 38 plays, and is the earliest, most reliable extant source for half of them.

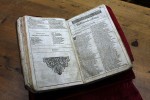

There are differences between this copy and the 232 other ones known to survive. The printers made corrections and alterations throughout the original print run of around 800, so each First Folio is a unique work. In addition to the printing differences, the Saint-Omer copy is also missing the entire text of Two Gentlemen of Verona; the pages were deliberately torn out. There are also annotations that suggest the volume was used for performances. Some of the words are replaced with more modern language, and a character in Henry IV is changed from “hostess” to “host” and from “wench” to “fellow” with utter disregard for iambic pentameter.

There are differences between this copy and the 232 other ones known to survive. The printers made corrections and alterations throughout the original print run of around 800, so each First Folio is a unique work. In addition to the printing differences, the Saint-Omer copy is also missing the entire text of Two Gentlemen of Verona; the pages were deliberately torn out. There are also annotations that suggest the volume was used for performances. Some of the words are replaced with more modern language, and a character in Henry IV is changed from “hostess” to “host” and from “wench” to “fellow” with utter disregard for iambic pentameter.

The library has had the book in its stacks for 400 years, thanks to its arrangement with the now-defunct college of Jesuits in Saint-Omer which used the city library’s Heritage Room as its own library. Saint-Omer is a small town now, but in the Middle Ages it was an important city with the fourth greatest library in Western Europe. The Jesuit college was founded in the late 16th century when Catholics were forbidden by law to attend college in English. They could just cross the Channel and get an education in France instead, and Saint-Omer was well attended by English Catholics.

The library has had the book in its stacks for 400 years, thanks to its arrangement with the now-defunct college of Jesuits in Saint-Omer which used the city library’s Heritage Room as its own library. Saint-Omer is a small town now, but in the Middle Ages it was an important city with the fourth greatest library in Western Europe. The Jesuit college was founded in the late 16th century when Catholics were forbidden by law to attend college in English. They could just cross the Channel and get an education in France instead, and Saint-Omer was well attended by English Catholics.

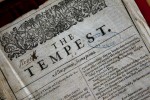

One particularly intriguing note is the name “Nevill” written on the first page of The Tempest (also the first page of the book entire since the title pages are gone). It could be the explanation of how the folio got to Saint-Omer since there is only one other known copy in the whole country. Neville was a name adopted by several members of the Scarisbrick family, a prominent Catholic family of landed gentry with a pedigree stretching back to the 1200s. Edward Scarisbrick (Neville), born in 1639, was educated at the Jesuit college of St. Omer, and, following in the footsteps of others in his family, became a Jesuit in 1660.

One particularly intriguing note is the name “Nevill” written on the first page of The Tempest (also the first page of the book entire since the title pages are gone). It could be the explanation of how the folio got to Saint-Omer since there is only one other known copy in the whole country. Neville was a name adopted by several members of the Scarisbrick family, a prominent Catholic family of landed gentry with a pedigree stretching back to the 1200s. Edward Scarisbrick (Neville), born in 1639, was educated at the Jesuit college of St. Omer, and, following in the footsteps of others in his family, became a Jesuit in 1660.

There’s some speculation that the find may be relevant to the question of whether William Shakespeare was a secret Catholic, but I don’t see how. Shakespeare was dead and gone when this book got to Saint-Omer. It could be relevant to how Catholics read and performed his plays in the 17th century; I doubt it goes beyond that.

There’s some speculation that the find may be relevant to the question of whether William Shakespeare was a secret Catholic, but I don’t see how. Shakespeare was dead and gone when this book got to Saint-Omer. It could be relevant to how Catholics read and performed his plays in the 17th century; I doubt it goes beyond that.

First Folios are of course very valuable. One sold at Sotheby’s in 2006 for $5.2 million, but this copy would not be so expensive because of its missing pages. It doesn’t matter anyway, because there is no way the library is selling it. As Rémy Cordonnier notes succinctly: “It is an inalienable property that cannot be sold, like all the works of the library.”

It will be conserved for a while and then put on display some time next year. There are also tentative plans to scan it and make it available on the library’s website.