Unfinished sketches have been discovered on the back of watercolors by Paul Cézanne in the collection of the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. The watercolors, previously on display in room 20 of the Collection Gallery, had been out of their frames before, but the backs were hidden behind brown paper. It was that brown paper backing, ironically, that spurred the discovery of what it had been hiding for a century a so.

Brown paper is highly acidic. Over time the acid migrates from the backing into the original paper medium causing it to darken and become brittle. The Barnes Foundation knew that five Cézanne watercolor landscapes needed to have the brown paper backing removed and in January of 2014, all five of them were sent as part of a group of 22 works to the Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts (CCAHA), also in Philadelphia, for treatment.

Photographs © 2015 The Barnes Foundation.

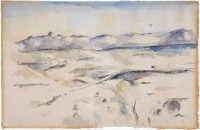

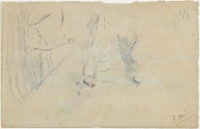

CCAHA paper conservator Gwenanne Edwards was painstakingly removing the backing from the 1885-1886 watercolor entitled The Chaîne de l’Etoile Mountains with a microspatula when she saw swirls of blue and green and some pencil lines. Once the backing was entirely removed, an unfinished sketch of trees done in pencil and then accented with watercolors was revealed. It’s hard to determine exactly what the subject is since the sketch is so incomplete, possibly a path winding through trees with a square well in the center. The bottom right corner has a pencil note on it, an “X” and the word “Non” with what appears to be a question mark after it. This is not the work of the artist; it’s probably a notation from a dealer on whether its saleable.

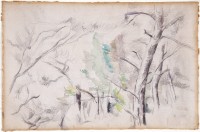

Behind the backing of the second watercolor, Trees, conservators found a much more detailed graphite-only sketch of a manor house and farmhouse with a mountain in the background. Denis Coutagne, president of the Société Paul Cezanne in Provence, researched the drawing and identified the location as the Pilon du Roi peak in the same Massif de l’Etoile mountain range in Aix-en-Provence, southern France, depicted in the first watercolor. This was one of Cézanne’s favorite locations which he painted and drew many times over.

Photographs © 2015 The Barnes Foundation.

It was not uncommon for Cézanne to work on both sides of the paper in his sketchbooks and on larger, individual sheets such as these, and over the course of his career he produced thousands of drawings, some of which were done in preparation for oil paintings, but most often they were a place to experiment with line and color. “These sketches offer a window into Cezanne’s artistic process, which is truly invaluable,” said Barbara Buckley, Senior Director of Conservation and Chief Conservator of Paintings at the Barnes Foundation.

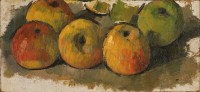

The five brown paper-backed watercolors were acquired by millionaire chemist and eccentric art collector Albert Barnes in 1921. The seller was Leo Stein, author Gertrude Stein‘s brother, who between 1904 and 1914 had built with his sister an exceptional collection of modernist works in their shared apartment at 27 rue de Fleurus in Paris. Leo Stein was a particular devotee of Cézanne, so much so that when they dissolved their household and split up the collection in 1914, Leo let Gertrude have all the Picassos and most of the Matisses but insisted on keeping Cézanne’s small 4 3⁄4 by 10-inch oil painting Five Apples (now in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene V. Thaw).

The five brown paper-backed watercolors were acquired by millionaire chemist and eccentric art collector Albert Barnes in 1921. The seller was Leo Stein, author Gertrude Stein‘s brother, who between 1904 and 1914 had built with his sister an exceptional collection of modernist works in their shared apartment at 27 rue de Fleurus in Paris. Leo Stein was a particular devotee of Cézanne, so much so that when they dissolved their household and split up the collection in 1914, Leo let Gertrude have all the Picassos and most of the Matisses but insisted on keeping Cézanne’s small 4 3⁄4 by 10-inch oil painting Five Apples (now in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene V. Thaw).

Leo Stein and Albert Barnes had been friends for years at the time of the sale, bonded by their shared love of art. When financial difficulties forced Stein to sell some of his collection, he asked Barnes to arrange the sale of some pieces in the United States. Barnes wrote to Stein that he had been unable to find buyers for the five watercolor landscapes because nobody he had contacted “seems to think they are sufficiently important to want to own them.” We can’t be sure whether that was in fact the case or if Barnes was being economical with the truth in order to score a bargain, but the final result was Barnes acquiring all five for $100 each.

There is no evidence in the correspondence that either Stein or Barnes had any idea there were sketches on the back of two of them. Given the probable dealer pencil markings on one of the sketches, it’s likely that the backs of the watercolors had already been covered with paper before Stein bought them.

The newly discovered sketches will be on display in double-sided frames in the second floor classroom of the Barnes Foundation from April 10th through May 18th, after which they will return to their former one-sided display in Room 20. This is an extremely rare opportunity to see anything at all from the Barnes collection not in its assigned location. Barnes left very strict, very specific instructions on the management of the art in Foundation’s charter. One of the rules is all the works have to be displayed exactly where

The newly discovered sketches will be on display in double-sided frames in the second floor classroom of the Barnes Foundation from April 10th through May 18th, after which they will return to their former one-sided display in Room 20. This is an extremely rare opportunity to see anything at all from the Barnes collection not in its assigned location. Barnes left very strict, very specific instructions on the management of the art in Foundation’s charter. One of the rules is all the works have to be displayed exactly where Barnes chose to display them, never moved, never removed, never sold, never loaned. Even taking down works for conservation purposes requires the permission of the Pennsylvania Attorney General. Barnes arranged his art the way he liked it, a configuration he felt most in keeping with his Deweyite educational principles. The Foundation was to be an educational institution for students of art, not a museum for the general public.

Barnes chose to display them, never moved, never removed, never sold, never loaned. Even taking down works for conservation purposes requires the permission of the Pennsylvania Attorney General. Barnes arranged his art the way he liked it, a configuration he felt most in keeping with his Deweyite educational principles. The Foundation was to be an educational institution for students of art, not a museum for the general public.

Those rules have since been challenged by the foundation’s board, most notably in the controversial decision to break Albert Barnes’ will and move the entire collection from Barnes’ home in Merion, five miles outside of Philadelphia, to a new, larger facility on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in metro Philly. The excellent but agonizing 2009 documentary The Art of the Steal (available on Netflix streaming or for rent on Amazon Instant) covered the shenanigans involved. You can read the Barnes Foundation’s rebuttal to the documentary here.

Those rules have since been challenged by the foundation’s board, most notably in the controversial decision to break Albert Barnes’ will and move the entire collection from Barnes’ home in Merion, five miles outside of Philadelphia, to a new, larger facility on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in metro Philly. The excellent but agonizing 2009 documentary The Art of the Steal (available on Netflix streaming or for rent on Amazon Instant) covered the shenanigans involved. You can read the Barnes Foundation’s rebuttal to the documentary here.