Archaeologists from the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) have unearthed a rare 14th century devotional panel dedicated to the death of rebel-turned-martyr Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster. The team was excavating the north bank of the Thames near London Bridge in advance of construction in 2000 when they found the rare piece in a medieval land reclamation dump. The waterlogged soil of the Thames riverbank is an outstanding preserver of artifacts, and this lead alloy panel with its delicate openwork has survived in excellent condition along with organic artifacts like timber revetments from the Roman period and the Middle Ages, the remains of plants used for cloth dyeing and a medieval leather knife sheath.

Archaeologists from the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) have unearthed a rare 14th century devotional panel dedicated to the death of rebel-turned-martyr Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster. The team was excavating the north bank of the Thames near London Bridge in advance of construction in 2000 when they found the rare piece in a medieval land reclamation dump. The waterlogged soil of the Thames riverbank is an outstanding preserver of artifacts, and this lead alloy panel with its delicate openwork has survived in excellent condition along with organic artifacts like timber revetments from the Roman period and the Middle Ages, the remains of plants used for cloth dyeing and a medieval leather knife sheath.

The panel was originally a mass-produced object sold at a pilgrimage site dedicated to the earl. People bought them as devotional objects, often for use in small home shrines. Thomas Plantagenet, Earl of Lancaster, would not at first glance seem to be the ideal subject for religious reverence. A holy man he was not. What he was was a powerful baron, the holder of no fewer than five major earldoms (Lancaster, Lincoln, Salisbury, Leicester, Derby) that made him the second wealthiest man in England after the king, the paternal grandson King Henry III of England and a thorn in the side of the unpopular King Edward II, his cousin.

At first Thomas supported Edward, but the bloom was soon off the rose, in large part thanks to Edward’s lavishing of titles, monies and power on his low-born favorite Piers Gaveston. By 1311, three years after he’d carried Curtana, the sword of St. Edward the Confessor, at his cousin’s coronation, Thomas was the leader of the Ordainers, a group of barons, earls and bishops demanding, among other things, that Gaveston be exiled. When Gaveston returned less than two months after this his third exile and Edward gave him all his lands and titles back, the Ordainers went to war. He was captured, tried and beheaded. Lancaster was one of the judges and Gaveston was executed on his property.

At first Thomas supported Edward, but the bloom was soon off the rose, in large part thanks to Edward’s lavishing of titles, monies and power on his low-born favorite Piers Gaveston. By 1311, three years after he’d carried Curtana, the sword of St. Edward the Confessor, at his cousin’s coronation, Thomas was the leader of the Ordainers, a group of barons, earls and bishops demanding, among other things, that Gaveston be exiled. When Gaveston returned less than two months after this his third exile and Edward gave him all his lands and titles back, the Ordainers went to war. He was captured, tried and beheaded. Lancaster was one of the judges and Gaveston was executed on his property.

From then on it was one fight after the other between the royal cousins. For a while Lancaster had the upper hand in a big way, becoming the de facto king after Edward’s army was defeated by the forces of Robert the Bruce at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, but in 1318 he was ousted and the two Hugh Despensers, father and son, took over as power behind the throne and Edward’s favorite. Lancaster marshalled his private army, struck up a deal with Robert the Bruce and rebelled against the crown.

On March 16th, 1322, Lancaster and the King’s allies went head to head at the Battle of Boroughbridge. Lancaster lost. He was taken prisoner and tried for treason in a sham court (the judges included both Despensers and the King) in his own castle at Pontefract where he was not allowed to speak in his own defense. He was convicted, of course, and on March 23rd, he was executed by beheading (Edward had commuted the traditional sentence of hanging, drawing and quartering on account of Lancaster’s royal blood).

Within weeks after Lancaster’s execution, shrines dedicated to him began to crop up, at the site of his execution at Pontefract Castle, his tomb in Pontefract Priory and at Old St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Rumors of miracles at the priory tomb and execution site abounded and soon Thomas was venerated as a popular saint. He was so popular Edward II put an armed guard around the priory to keep the crowds away. In response money was raised from all over England to build a chantry chapel on the site of his execution.

Within weeks after Lancaster’s execution, shrines dedicated to him began to crop up, at the site of his execution at Pontefract Castle, his tomb in Pontefract Priory and at Old St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Rumors of miracles at the priory tomb and execution site abounded and soon Thomas was venerated as a popular saint. He was so popular Edward II put an armed guard around the priory to keep the crowds away. In response money was raised from all over England to build a chantry chapel on the site of his execution.

His saintliness rested not in his personal piety or holy behavior (there certainly wasn’t much of the latter), but in his rebellion against a despised king. This was a thing in Medieval England: make saints out of fallen political/military heroes. Simon de Montfort received similar devotions after his death in 1265. What better way for Edward III to distance himself from his father after Edward II’s murder than to side with the cult of St. Thomas of Lancaster? In 1327 petitioned Pope John XXII that Thomas be canonized as an official saint of the Church, but it never happened.

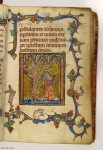

Notwithstanding his lack of a Church-sanctioned halo, Thomas continued to be revered locally at least until the Dissolution of the Monasteries. His relics were believed to hold specific healing properties — his belt helped women in labour, his hat cured migraines — and a hymn called the Lancaster Suffrage was included as part of the daily prayers in the psalters and Books of Hours of wealthy Lancastrians. Here’s the one from Manuscript 13 (ca. 1330) in the Bridewell Library at Southern Methodist University:

Notwithstanding his lack of a Church-sanctioned halo, Thomas continued to be revered locally at least until the Dissolution of the Monasteries. His relics were believed to hold specific healing properties — his belt helped women in labour, his hat cured migraines — and a hymn called the Lancaster Suffrage was included as part of the daily prayers in the psalters and Books of Hours of wealthy Lancastrians. Here’s the one from Manuscript 13 (ca. 1330) in the Bridewell Library at Southern Methodist University:

Antiphon: Oh Thomas, Earl of Lancaster,

Jewel and flower of knighthood,

Who in the name of God,

For the sake of the state of England,

Offered yourself to be killed.

Versicle: Pray for us, soldier of Christ.

Response: Who never held the poor worthless.

Collect: Almighty everlasting God, you who wished to honor your holy soldier Thomas of Lancaster through the lamentable palm of the martyr for the peace and state of England just as he is lead through the sacrament for God’s own exceeding glory [and] through your holy miracles. Bestow, we pray, that you grant all faithful venerating him a good journey and life eternal. Through Christ our Lord, Amen.

For people who could not afford to have French illuminators make them their own personal prayer books, devotional panels provided a less expensive entre into the private veneration of St. Thomas. Although they were very popular in the 14th century, few of these panels have survived. The British Museum has two examples, one smaller and one larger, neither of them are in great condition. The figures on the smaller piece are crudely designed and while the larger panel has an elaborate Gothic cathedral-like structure and more people in it than the MOLA panel, they aren’t as finely crafted and the piece is fragmented. You can see in the picture that it’s being held together with wires.

For people who could not afford to have French illuminators make them their own personal prayer books, devotional panels provided a less expensive entre into the private veneration of St. Thomas. Although they were very popular in the 14th century, few of these panels have survived. The British Museum has two examples, one smaller and one larger, neither of them are in great condition. The figures on the smaller piece are crudely designed and while the larger panel has an elaborate Gothic cathedral-like structure and more people in it than the MOLA panel, they aren’t as finely crafted and the piece is fragmented. You can see in the picture that it’s being held together with wires.

The MOLA piece is five inches high and 3.5 inches wide and divided into four scenes that are to be read clockwise from the top left. In scene one, Thomas is captured. The caption in French reads “Here I am taken prisoner.” In scene two he is put on trial. The caption reads “I am judged.” In scene three he is convicted and conveyed by horse (the quality, or lack thereof, of this horse was a big issue in some of the chronicles) to the site of execution. The caption: “I am under threat.” In the last scene Thomas is beheaded by sword. The caption states simply: “la mort” (death). These shenanigans are presided over by Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary, perched atop the sun and moon, waiting to welcome Lancaster’s saintly soul to heaven.

The MOLA piece is five inches high and 3.5 inches wide and divided into four scenes that are to be read clockwise from the top left. In scene one, Thomas is captured. The caption in French reads “Here I am taken prisoner.” In scene two he is put on trial. The caption reads “I am judged.” In scene three he is convicted and conveyed by horse (the quality, or lack thereof, of this horse was a big issue in some of the chronicles) to the site of execution. The caption: “I am under threat.” In the last scene Thomas is beheaded by sword. The caption states simply: “la mort” (death). These shenanigans are presided over by Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary, perched atop the sun and moon, waiting to welcome Lancaster’s saintly soul to heaven.

This is the only Lancaster devotional panel known to have French labels explaining each scene. It’s also the only one known with surviving gilding which highlights the sun and moon.

Up until now the panel has only been known by Museum of London experts, but the riverbank excavation, including detailed information about the panel, has just been published (Roman and Medieval Revetments on the Thames Waterfront) so the museum is putting the panel on display for the first time. The exhibition in the museum’s Medieval Galleries will run from March 28th to September 28th of this year.

Up until now the panel has only been known by Museum of London experts, but the riverbank excavation, including detailed information about the panel, has just been published (Roman and Medieval Revetments on the Thames Waterfront) so the museum is putting the panel on display for the first time. The exhibition in the museum’s Medieval Galleries will run from March 28th to September 28th of this year.