A set of white-tailed eagle talons recovered from the 130,000-year-old Krapina Neanderthal site in Croatia have multiple cut marks, notches and polished facets that indicate the talons were once mounted in a piece of jewelry. Individual talons thought to have been used as pendants have been found at Neanderthal sites before, but this group of eight talons collected from at least three eagles was used for a more elaborate ornament that likely held symbolic meaning. Crafted early in the Middle Paleolithic era long before anatomically modern humans arrived in Europe about 45,000 years ago, the talons are evidence that Neanderthals created complex ornaments with symbolic significance independently of any later interactions with Homo sapiens sapiens.

A set of white-tailed eagle talons recovered from the 130,000-year-old Krapina Neanderthal site in Croatia have multiple cut marks, notches and polished facets that indicate the talons were once mounted in a piece of jewelry. Individual talons thought to have been used as pendants have been found at Neanderthal sites before, but this group of eight talons collected from at least three eagles was used for a more elaborate ornament that likely held symbolic meaning. Crafted early in the Middle Paleolithic era long before anatomically modern humans arrived in Europe about 45,000 years ago, the talons are evidence that Neanderthals created complex ornaments with symbolic significance independently of any later interactions with Homo sapiens sapiens.

The eight talons and one pedal phalanx (the toe bone associated with one of the talons) were found in the same level of a rock shelter on Hušnjak hill, near the Croatian town of Krapina, that was excavated by Croatian paleontologist Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger from 1899 to 1905. They were in the uppermost level which Gorjanović-Kramberger called the “Ursus spelaeus zone” because of its many cave bear bones. Although most of the Neanderthal bones were found more than halfway down site (level 4 on the diagram, labeled “Homo sapiens” because when it was drawn they hadn’t figured out yet that the bones belonged to another species of human), stone tools and one hearth were also found on the bear level confirming its use by Neanderthals. The entire site from top to bottom has a relatively short date span of about 10,000 years.

The eight talons and one pedal phalanx (the toe bone associated with one of the talons) were found in the same level of a rock shelter on Hušnjak hill, near the Croatian town of Krapina, that was excavated by Croatian paleontologist Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger from 1899 to 1905. They were in the uppermost level which Gorjanović-Kramberger called the “Ursus spelaeus zone” because of its many cave bear bones. Although most of the Neanderthal bones were found more than halfway down site (level 4 on the diagram, labeled “Homo sapiens” because when it was drawn they hadn’t figured out yet that the bones belonged to another species of human), stone tools and one hearth were also found on the bear level confirming its use by Neanderthals. The entire site from top to bottom has a relatively short date span of about 10,000 years.

Only the cliff face is left today, but Gorjanović-Kramberger extensively documented and published the site and its contents — hundreds of Neanderthal bones and teeth, 2800 faunal remains, more than 800 stone tools — have been preserved at the Croatian Natural History Museum in Zagreb where he was head of the Geological-Paleontological Department. Davorka Radovcic was reviewing the Natural History Museum’s Krapina Neanderthal collection in late 2013 after she was appointed its curator when she noticed the cut marks on the phalanx bone from the eagle talon set. Radovcic realized that the marks were made by humans. An international study of the talons ensued, the results of which were published earlier this month in the journal PLOS ONE.

Only the cliff face is left today, but Gorjanović-Kramberger extensively documented and published the site and its contents — hundreds of Neanderthal bones and teeth, 2800 faunal remains, more than 800 stone tools — have been preserved at the Croatian Natural History Museum in Zagreb where he was head of the Geological-Paleontological Department. Davorka Radovcic was reviewing the Natural History Museum’s Krapina Neanderthal collection in late 2013 after she was appointed its curator when she noticed the cut marks on the phalanx bone from the eagle talon set. Radovcic realized that the marks were made by humans. An international study of the talons ensued, the results of which were published earlier this month in the journal PLOS ONE.

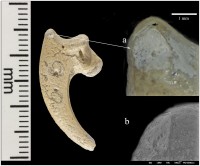

The study examined each bone in microscopic detail and found that four of the talons and the phalanx have multiple cut marks whose edges have been smoothed, eight talons have been polished and/or abraded and three have notches in approximately the same area. Those smooth edges are how we know the cuts weren’t the result of butchering. Other fauna in the rock shelter bears the sharp cut marks of the butchering process and none of them have smoothed edges. This was done deliberately, probably by wrapping the talon in a fiber of some kind. The shiny polished areas look like what happens when bone rubs against bone. The research team believes these are the tell-tale signs of the claws having been mounted in a necklace or bracelet.

The study examined each bone in microscopic detail and found that four of the talons and the phalanx have multiple cut marks whose edges have been smoothed, eight talons have been polished and/or abraded and three have notches in approximately the same area. Those smooth edges are how we know the cuts weren’t the result of butchering. Other fauna in the rock shelter bears the sharp cut marks of the butchering process and none of them have smoothed edges. This was done deliberately, probably by wrapping the talon in a fiber of some kind. The shiny polished areas look like what happens when bone rubs against bone. The research team believes these are the tell-tale signs of the claws having been mounted in a necklace or bracelet.

At Krapina, cut marks on the pedal phalanx and talons are not related to feather removal or subsistence, so these must be the result of severing tendons for talon acquisition. Further evidence for combining these in jewelry is edge smoothing of the cut marks, the small polished facets, medial/lateral sheen and nicks on some specimens. All are a likely manifestation of the separating the bones from the foot and the attachment of the talons to a string or sinew. Cut marks on many aspects, but not the plantar surfaces, illustrate the numerous approaches the Neandertals had for severing the bones and mounting them into a piece of jewelry.

At Krapina, cut marks on the pedal phalanx and talons are not related to feather removal or subsistence, so these must be the result of severing tendons for talon acquisition. Further evidence for combining these in jewelry is edge smoothing of the cut marks, the small polished facets, medial/lateral sheen and nicks on some specimens. All are a likely manifestation of the separating the bones from the foot and the attachment of the talons to a string or sinew. Cut marks on many aspects, but not the plantar surfaces, illustrate the numerous approaches the Neandertals had for severing the bones and mounting them into a piece of jewelry.

As in ethnohistoric-present societies, the Neandertals’ practice of catching eagles very likely involved planning and ceremony. We cannot know the way they were captured, but if collected from carcasses it must have taken keen eyes to locate the dead birds as rare as they were in the prehistoric avifauna. We suspect that the collection of talons from at least three different white-tailed eagles mitigates against recovering carcasses in the field, but more likely represents evidence for live capture. In any case, these talons provide multiple new lines of evidence for Neandertals’ abilities and cultural sophistication. They are the earliest evidence for jewelry in the European fossil record and demonstrate that Neandertals possessed a symbolic culture long before more modern human forms arrived in Europe.

As in ethnohistoric-present societies, the Neandertals’ practice of catching eagles very likely involved planning and ceremony. We cannot know the way they were captured, but if collected from carcasses it must have taken keen eyes to locate the dead birds as rare as they were in the prehistoric avifauna. We suspect that the collection of talons from at least three different white-tailed eagles mitigates against recovering carcasses in the field, but more likely represents evidence for live capture. In any case, these talons provide multiple new lines of evidence for Neandertals’ abilities and cultural sophistication. They are the earliest evidence for jewelry in the European fossil record and demonstrate that Neandertals possessed a symbolic culture long before more modern human forms arrived in Europe.