Yale University music historian Rebekah Ahrendt was researching a theatrical troupe that entertained audiences in turn of the 18th century The Hague when she came across a notice in a 1938 French journal describing a collection of undelivered letters at a museum. Intrigued, Ahrendt tracked down the collection at the Museum voor Communicatie in The Hague where it had lain undisturbed and unremarked since 1926. She found a trunk waterproofed with sealskin and filled with 2,600 letters sent from France, Spain and the Spanish Netherlands between 1689 and 1707.

Yale University music historian Rebekah Ahrendt was researching a theatrical troupe that entertained audiences in turn of the 18th century The Hague when she came across a notice in a 1938 French journal describing a collection of undelivered letters at a museum. Intrigued, Ahrendt tracked down the collection at the Museum voor Communicatie in The Hague where it had lain undisturbed and unremarked since 1926. She found a trunk waterproofed with sealskin and filled with 2,600 letters sent from France, Spain and the Spanish Netherlands between 1689 and 1707.

The letters were collected by The Hague postmasters Simon de Brienne and his wife, Maria Germain. Any letters that could not be delivered because the recipients could not be found, or if found they refused receipt or could not or would not pay the postage due, the couple kept. (At the time the recipient paid postage, not the sender.) Most postmasters destroyed such letters, but the de Briennes hoped someone might someday take delivery and pay the postage so they put them in the trunk as a kind of fingers-crossed savings account.

The letters were collected by The Hague postmasters Simon de Brienne and his wife, Maria Germain. Any letters that could not be delivered because the recipients could not be found, or if found they refused receipt or could not or would not pay the postage due, the couple kept. (At the time the recipient paid postage, not the sender.) Most postmasters destroyed such letters, but the de Briennes hoped someone might someday take delivery and pay the postage so they put them in the trunk as a kind of fingers-crossed savings account.

Simon de Brienne was good at making money. Born in France, he was a servant of Prince Rupert of the Rhine, the younger son of German prince Frederick V, Elector Palatine, and maternal nephew of King Charles I of England. He was arrived in The Hague in 1669 and was appointed Postmaster seven years later. His wife was appointed postmistress in 1686. His new job didn’t stop Simon from working his royal connections. He was employed as chamberlain to William of Nassau, Prince of Orange, and when his boss became King William III of England, Scotland, and Ireland in the Glorious Revoultion of 1688, the Briennes went with him to England. As a trusted confidant, Simon was given a plum position as Keeper of the Wardrobe at Kensington Palace in 1689. Ten years later, he sold the office for £1550 and a cask of the best Burgundy wine. They returned to The Hague shortly thereafter.

Simon de Brienne was good at making money. Born in France, he was a servant of Prince Rupert of the Rhine, the younger son of German prince Frederick V, Elector Palatine, and maternal nephew of King Charles I of England. He was arrived in The Hague in 1669 and was appointed Postmaster seven years later. His wife was appointed postmistress in 1686. His new job didn’t stop Simon from working his royal connections. He was employed as chamberlain to William of Nassau, Prince of Orange, and when his boss became King William III of England, Scotland, and Ireland in the Glorious Revoultion of 1688, the Briennes went with him to England. As a trusted confidant, Simon was given a plum position as Keeper of the Wardrobe at Kensington Palace in 1689. Ten years later, he sold the office for £1550 and a cask of the best Burgundy wine. They returned to The Hague shortly thereafter.

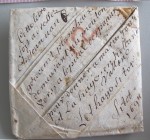

The collection, still in Simon de Brienne’s original trunk, was bequeathed to the museum in 1926. Out of the 2,600 letters in the trunk, 2,000 are opened and 600 are sealed. They include missives from people from all walks of life — noblemen, merchants, singers, actors, spies, peasants, Hugenot exiles, women, men — and are written in French, Spanish, Italian, Dutch and Latin. Most of the correspondence that has survived from this period was written by the elite. To have such a wide range of society represented in their own voice (many of the letters were written phonetically with little punctuation in the dialect of the writer rather than in the formal, educated hand of the highly literate) is unique.

The collection, still in Simon de Brienne’s original trunk, was bequeathed to the museum in 1926. Out of the 2,600 letters in the trunk, 2,000 are opened and 600 are sealed. They include missives from people from all walks of life — noblemen, merchants, singers, actors, spies, peasants, Hugenot exiles, women, men — and are written in French, Spanish, Italian, Dutch and Latin. Most of the correspondence that has survived from this period was written by the elite. To have such a wide range of society represented in their own voice (many of the letters were written phonetically with little punctuation in the dialect of the writer rather than in the formal, educated hand of the highly literate) is unique.

One open letter from the collection has been transcribed and translated manages to delicately suggest a pregnancy scandal without actually coming out and saying it. It was sent to a wealthy Jewish merchant in The Hague.

“I am writing on behalf of your friend and mine and she realized as soon as she left the opera company in The Hague to go to Paris that she had made a terrible mistake. Now she needs your help to come back to The Hague. You can divine without difficulty the true cause of her despair. I cannot put it into so many words; what I ought to say to you is so excessive. Content yourself with thinking on it, and returning her to life by procuring her return.”

The letter wound up in de Brienne’s collection because it is marked “niet hebben,” which means it was refused.

The letter wound up in de Brienne’s collection because it is marked “niet hebben,” which means it was refused.

It’s not just the content of the letters that are of interest to historians. Scholars who study paper, postal systems, economics, linguistics and seals will find in this collection a unique source of information from the late 17th and early 18th century. It will be an invaluable resource for the nascent study of letterlocking, the practice of folding a letter in complex ways to convert it into its own envelope.

Ahrendt has already made significant historical discoveries in her own specialty.

As a music historian, Ahrendt found the correspondence between musicians especially interesting and says the information these missives contain casts a different light on the development of the musical labor industry: “This archive is truly a cultural history of musicians. I was surprised to learn that musicians traveled so much during that time period. We have so few witnesses to describe what daily life was like for your average musician, and these letters tell of large networks of these musicians traveling frequently. This is completely different from what we previously believed about the history of musicians.”

Brienne also put his own records as postmaster in trunk, giving historians another unique view into the business of mail. The accounting books for incoming and outgoing mail lists the price for every letter.

Brienne also put his own records as postmaster in trunk, giving historians another unique view into the business of mail. The accounting books for incoming and outgoing mail lists the price for every letter.

blockquote>”We discovered how postal routes and the financial system of that time worked. There is documentation of the point at which you paid a rider or a boatman to transport your post. We learned about the connection between the post office in Hague and the post office in Paris. We even found nasty letters from the Parisian postmaster saying that he hadn’t been paid properly,” says Ahrendt.

This pearl of great price won’t just be available to those who are fortunate enough to study them in person. An interdisciplinary team of researchers from Yale University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the Universities of Leiden, Groningen, and Oxford is working on digitizing this exceptional archive. The project is called Signed, Sealed, & Undelivered and the website is already live although the content is limited as of yet. Right now the Letters section is a slideshow of beautiful high resolution images of seals and letters, some with brief summaries describing the image, some labeled only with an archive number. Click on the icon with the four boxes in the bottom right corner of the screen to browse the letters index via a topic gallery instead.

This pearl of great price won’t just be available to those who are fortunate enough to study them in person. An interdisciplinary team of researchers from Yale University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the Universities of Leiden, Groningen, and Oxford is working on digitizing this exceptional archive. The project is called Signed, Sealed, & Undelivered and the website is already live although the content is limited as of yet. Right now the Letters section is a slideshow of beautiful high resolution images of seals and letters, some with brief summaries describing the image, some labeled only with an archive number. Click on the icon with the four boxes in the bottom right corner of the screen to browse the letters index via a topic gallery instead.

Thanks to the latest scanning technology, the sealed letters won’t be opened, but they will seen nonetheless.

Thanks to the latest scanning technology, the sealed letters won’t be opened, but they will seen nonetheless.

Dr Nadine Akkerman, from the University of Leiden, says: “Because early modern ink contained iron, incredibly delicate scanning can detect it on the paper. By scanning each layer of paper in a letter packet, we should be able to piece the letters back like jigsaw puzzles and read them without breaking the seals.”

Earlier this year they tested the technology by creating a bundle of 20 stacked letters, each written with quills and iron gall ink, folded using period accurate letterlocking formats and sealed with two different kinds of wax. The bundle was then scanned with high contrast TDI CT (Time Delay Integration, computed tomography) and the contents were revealed without damaging the folds and seals. This video is a fly-through of the test: