The end of 2015 is upon us and so is what has become an annual tradition here, the Year in History Blog History. We had another milestone which, while the number was a tad on the random side, turned out to be my favorite milestone celebration ever. Why? Because we rang in six million pageviews with Steve Austin, astronaut, a man barely alive but somehow still able to rock the double-knit polyester leisure suit. I was surprised and delighted to find so many comments from people who love the Six Million Dollar Man as much as I do. Engine block Steve Austin action figure 4EVA!

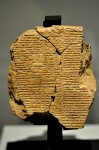

The most read story of the year going by pageviews was the one about the Dutch soccer hooligans vandalizing the newly restored Barcaccia fountain at the base of Rome’s Spanish Steps. Short on its heels was one of my favorite, if not the favorite, post of the year: the cuneiform tablet that added 20 more lines to the Epic of Gilgamesh. The awesomeness of the Viking blacksmith’s grave drew the third largest numbers of views, and the momentous discovery of an archaic home from the 6th century B.C. underneath the Quirinale Hill in Rome came in fourth.

The most read story of the year going by pageviews was the one about the Dutch soccer hooligans vandalizing the newly restored Barcaccia fountain at the base of Rome’s Spanish Steps. Short on its heels was one of my favorite, if not the favorite, post of the year: the cuneiform tablet that added 20 more lines to the Epic of Gilgamesh. The awesomeness of the Viking blacksmith’s grave drew the third largest numbers of views, and the momentous discovery of an archaic home from the 6th century B.C. underneath the Quirinale Hill in Rome came in fourth.

Number five on the list is also my favorite photograph of the year. It’s the CT scan of the cross-legged meditating Buddha statue that has a mummified person inside of it. I learned about the brutal process of self-mummification thanks to that post, which was horrifying and fascinating at the same time if not in equal measure, even though the CT scan showed the internal organs had been removed so the person inside the statue hadn’t actually gotten that way by starving, dehydrating and poisoning himself over the course of six years.

Number five on the list is also my favorite photograph of the year. It’s the CT scan of the cross-legged meditating Buddha statue that has a mummified person inside of it. I learned about the brutal process of self-mummification thanks to that post, which was horrifying and fascinating at the same time if not in equal measure, even though the CT scan showed the internal organs had been removed so the person inside the statue hadn’t actually gotten that way by starving, dehydrating and poisoning himself over the course of six years.

That post also corrected an error that was widespread in the general media coverage of the Buddha mummy, namely that its presence inside the statue was revealed by the CT scan. The statue was part of a traveling museum exhibition about mummies, so obviously the fact that there was a mummy inside the state was already known. That’s why they scanned it in the first place. Still, once a mistake like that gets into a headline or a lede, it’s almost impossible to carve it out. The days of a front page correction fixing the problem are over.

That goes double for a big mistake in History.com’s Today in History feature. I informed History.com that they had confused 18th century surveyor Andrew Ellicott with his great-grandson and dendrochronology pioneer Andrew Ellicott Douglass in their entry on the first recorded observation of a meteor shower in North America. I got an email back saying they were looking into it, but their erroneous article still stands. Perhaps they’ll have fixed it by the time November 12th comes around next year.

Another widespread story that needed some correcting is runner-up for favorite picture: the sale of the “world’s greatest cat painting.” Carl Kahler’s monumental 1893 painting of wealthy San Francisco socialite and philanthropist Kate Birdsall Johnson’s 43 cats sold for $826,000 made news all over the cat-loving Internet. Mrs. Johnson came off of her posthumous virality a little the worse for wear since apocryphal stories of her being a crazy cat lady with hundreds of cats roaming the house got repeated over and over again. In fact she was a thoughtful, devout, generous person who left valuable property and monies in her will to found a hospital for indigent women and children. That hospital still exists, albeit in a new location (the old one was felled in the 1906 earthquake) and under a new name.

Another widespread story that needed some correcting is runner-up for favorite picture: the sale of the “world’s greatest cat painting.” Carl Kahler’s monumental 1893 painting of wealthy San Francisco socialite and philanthropist Kate Birdsall Johnson’s 43 cats sold for $826,000 made news all over the cat-loving Internet. Mrs. Johnson came off of her posthumous virality a little the worse for wear since apocryphal stories of her being a crazy cat lady with hundreds of cats roaming the house got repeated over and over again. In fact she was a thoughtful, devout, generous person who left valuable property and monies in her will to found a hospital for indigent women and children. That hospital still exists, albeit in a new location (the old one was felled in the 1906 earthquake) and under a new name.

It was a particular good year for film discoveries, I think. I don’t just mean lost films that were found hiding out in vaults, but personal discoveries, films that were known but that I discovered in 2015. The most important actual discovery of the year was the film of the 1915 Eastland disaster found in Dutch newsreels. The ship which killed 844 people when it capsized while still moored just feet from the bank of the Chicago River was captured in important photographs by groundbreaking photojournalist Jun Fujita, but this is the first film of the disaster known to have survived.

As far as personal finds go, I still laugh like an idiot at Douglas Fairbanks as the brave, clueless, high as a kite detective Coke Ennyday. That was a random surprise find. Finding The Daughter of Dawn on Netflix, on the other hand, was the happy outcome of years of checking in on the story. I’ve been anxious to see the rediscovered treasure since I first wrote about it in 2012, and much to my amazement, it did not disappoint even after years of buildup. It’s a great picture in many ways, capturing an era that was bygone even as it was being filmed.

As far as personal finds go, I still laugh like an idiot at Douglas Fairbanks as the brave, clueless, high as a kite detective Coke Ennyday. That was a random surprise find. Finding The Daughter of Dawn on Netflix, on the other hand, was the happy outcome of years of checking in on the story. I’ve been anxious to see the rediscovered treasure since I first wrote about it in 2012, and much to my amazement, it did not disappoint even after years of buildup. It’s a great picture in many ways, capturing an era that was bygone even as it was being filmed.

My favorite videos of the year were all about the technology and procedure of historical preservation and exploration. First there was the all-too-brief view of how Historic Royal Palaces conservators go about washing the fragile 17th century tapestries under their care. With all the custom technology — the giant horizontal car wash made specifically for tapestries — the best part was how tenderly the conservators sponge away the dirt and blot away the moisture. The composite video made from synchroton X-ray imaging of a corroded 17th century metal box blew my mind purely from a tech standpoint. The detail and resolution of the images opens up a world of new possibilities for non-invasive exploration of artifacts that are otherwise too fragile to be touched.

Speaking of history and technology, the discovery that an eye salve from Bald’s Leechbook, a 10th century Anglo-Saxon book of remedies for illness, kills MRSA superbug bacteria with ruthless efficiency could have enormous implications in our soon-to-be post-antibiotic world. There were some heartbreaking responses to that story from people who have lived for years with persistent infections and are desperate to find a solution. Here’s hoping the research gets all the support it needs going forward so they don’t have to crowdfund for a measly £1,000 to hire a summer intern.

Is it weird if I transition from bacterial infection to poop? Oh well, at least there’s some sort of segue in there, even if it is a pathogenic one. Let’s face, it’s not a good History Blog year without some good poop stories, like the 25 tons of pigeon poop cleaned out of the 14th c. tower in Rye, a medieval city on the English Channel coast. Also we saw the greatest of all updates to the story of the barrels of poop found in Odense, Denmark. Researchers sifting through compacted 14th century excrement one teaspoon at a time, a designated expert poop-sniffer, museum Smell-O-Vision: that post and its comment thread made me inordinately happy. As did the hidden pooper found in the 17th century Dutch painting by Royal Collection curators.

Is it weird if I transition from bacterial infection to poop? Oh well, at least there’s some sort of segue in there, even if it is a pathogenic one. Let’s face, it’s not a good History Blog year without some good poop stories, like the 25 tons of pigeon poop cleaned out of the 14th c. tower in Rye, a medieval city on the English Channel coast. Also we saw the greatest of all updates to the story of the barrels of poop found in Odense, Denmark. Researchers sifting through compacted 14th century excrement one teaspoon at a time, a designated expert poop-sniffer, museum Smell-O-Vision: that post and its comment thread made me inordinately happy. As did the hidden pooper found in the 17th century Dutch painting by Royal Collection curators.

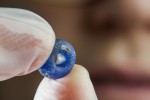

The hidden pooper may be my favorite restoration find, but my favorite artifact find of the year is probably the Roman owl fibula found on Danish island of Bornholm. Its bright enameled colors, rarity and sheer cuteness completely won me over. If Lorenzo ever graduates from making Mjölnir amulets out of his mom’s tea spoons into a full-fledged artifact reproduction business, I vote he make us a whole bunch of Bornholm owls.

The hidden pooper may be my favorite restoration find, but my favorite artifact find of the year is probably the Roman owl fibula found on Danish island of Bornholm. Its bright enameled colors, rarity and sheer cuteness completely won me over. If Lorenzo ever graduates from making Mjölnir amulets out of his mom’s tea spoons into a full-fledged artifact reproduction business, I vote he make us a whole bunch of Bornholm owls.

Close seconds are the blackboards from 1917 discovered with beautiful chalk artwork and class exercises preserved in pristine condition in an Oklahoma City school and the 132-year-old Winchester ’73 found leaning against tree in Great Basin National Park in the Snake mountains of eastern Nevada. Several comments on the latter story appreciated that I’d said conservators were keeping the rifle in its highly weathered condition “because it’s cool.” What’s funny is that I actually thought about it a lot when I was writing. I was going to break down all the reasons they’d decided not to restore it, but then I realized that it all boiled down to the same thing: because it’s cool. There are a million Winchester ’73s. This one stands out because some poor devil left it leaning against a tree for 130 years and now it looks kickass.

Close seconds are the blackboards from 1917 discovered with beautiful chalk artwork and class exercises preserved in pristine condition in an Oklahoma City school and the 132-year-old Winchester ’73 found leaning against tree in Great Basin National Park in the Snake mountains of eastern Nevada. Several comments on the latter story appreciated that I’d said conservators were keeping the rifle in its highly weathered condition “because it’s cool.” What’s funny is that I actually thought about it a lot when I was writing. I was going to break down all the reasons they’d decided not to restore it, but then I realized that it all boiled down to the same thing: because it’s cool. There are a million Winchester ’73s. This one stands out because some poor devil left it leaning against a tree for 130 years and now it looks kickass.

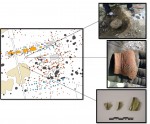

As far as precious metal finds go, the treasure of the year has to be the Bronze Age gold spirals found on Zealand, Denmark. They were found under a pile of gold coins and the spirals are so awesome they completely eclipsed the gold coin hoard. The comment thread on the spirals is particularly great too. Lots of interesting contributions from people who use or produce similar objects in embroidery and machining metal. The inscribed sword from the 13th or 14th century inspired a wealth of fascinating comments as well. Everyone likes a mystery, or at least we few, we nerdy few, we band of history-obsessed brothers do.

As far as precious metal finds go, the treasure of the year has to be the Bronze Age gold spirals found on Zealand, Denmark. They were found under a pile of gold coins and the spirals are so awesome they completely eclipsed the gold coin hoard. The comment thread on the spirals is particularly great too. Lots of interesting contributions from people who use or produce similar objects in embroidery and machining metal. The inscribed sword from the 13th or 14th century inspired a wealth of fascinating comments as well. Everyone likes a mystery, or at least we few, we nerdy few, we band of history-obsessed brothers do.

I also loved the comments on the story about the 7th century Christian skeletons found in front of the Temple of Concordia at Paestum because you were so enthusiastic about the fabulous hidden prostitute conspiracy story. One of the joys of writing this blog is when something that tickles me tickles y’all too. I love it even more when it’s a tangent that you pick up on rather than the main thread of the story. I’m not sure why. Validation that my meanderings were worthwhile, I suppose.

Sometimes the meandering becomes an entire post of its own, as in the case of Childeric’s treasure, a story I came across while researching something else I can’t remember anymore and that became something of an obsession for days. The story about Emily Post’s madcap road trip from coast to coast came about in much the same way.

Sometimes the meandering becomes an entire post of its own, as in the case of Childeric’s treasure, a story I came across while researching something else I can’t remember anymore and that became something of an obsession for days. The story about Emily Post’s madcap road trip from coast to coast came about in much the same way.

It’s been a heartbreaking year for history lovers. The destruction of so much of our shared cultural heritage in the Middle East by terrorism and war is almost unbearable. The brutal murder of Khaled el-Asaad, a great man who dedicated his life to the historic patrimony of Syria and the gave his life for it too, was an agonizing loss to his family, colleagues and all the rest of us who where so beholden to him without even realizing it until he was gone.

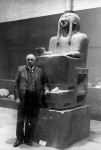

In the end, it’s history itself that soothes me even in such dark times. It wasn’t so long ago that Europe was facing the rubble of its own history, torn apart by total war. The sculptures and reliefs of Tell Halaf in Berlin were bombed to smithereens when the museum took a direct hit from an incendiary bomb in 1943. Seventy years later, they were put back together.

In the end, it’s history itself that soothes me even in such dark times. It wasn’t so long ago that Europe was facing the rubble of its own history, torn apart by total war. The sculptures and reliefs of Tell Halaf in Berlin were bombed to smithereens when the museum took a direct hit from an incendiary bomb in 1943. Seventy years later, they were put back together.

Three years ago, author Hilary Mantel, author of the exceptional Tudor historical fiction Wolf Hall, gave a speech about the public’s relationship to royal families at a London Review of Books event. It made the news because some media outlets plucked quotes about the Duchess of Cambridge and made them out to be cruel criticisms of the former Kate Middleton rather than the astute and apposite observation about how people, spurred on by an obsessive press, fetishize her and box her in. It’s a great speech, but the part that struck me most profoundly was about the discovery of the remains of Richard III.

Why are we all so pleased about digging up a king? Perhaps because the present is paying some of the debt it owes to the past, and science has come to the aid of history. The king stripped by the victors has been reclothed in his true identity. This is the essential process of history, neatly illustrated: loss, retrieval.

I’ve thought of that last line so many times this year, as horrific destruction followed horrific destruction. What was lost can be found again, even if its original form is gone forever. That is what history does. That is what we do every time we read history. We find what was lost.

Thank you all so very much for reading and commenting and sending me the kindest compliments and hottest story tips. May your 2016 be glorious.