The Prosecutor’s Office of Geneva returned two priceless earthenware sarcophaguses and 45 boxes of exceptional Etruscan artworks to Italy last month. They were found where tens of thousands of looted ancient artifacts worth hundreds of millions of dollars are usually found: in a giant warehouse at the Geneva Free Ports. They had been there for 15 years, stashed in the time of man’s innocency when looters, smugglers, middlemen and their brothers and sisters in the high-end antiquities market could do whatever the hell they wanted in Switzerland and nobody would question them.

The Prosecutor’s Office of Geneva returned two priceless earthenware sarcophaguses and 45 boxes of exceptional Etruscan artworks to Italy last month. They were found where tens of thousands of looted ancient artifacts worth hundreds of millions of dollars are usually found: in a giant warehouse at the Geneva Free Ports. They had been there for 15 years, stashed in the time of man’s innocency when looters, smugglers, middlemen and their brothers and sisters in the high-end antiquities market could do whatever the hell they wanted in Switzerland and nobody would question them.

Oh, if the walls of those warehouses could talk, what tales they would tell! Unique treasures fresh from the illegal dig, mud and salts still caked on the surface, files and Polaroids of even more unique treasures, many of them already in the hands of major museums, “Swiss private collection” ownership histories so blatantly fake they would make a seven-year-old forging a sick note from his mother stare in awed wonder at the sheer brazenness of it.

This particular smuggler’s cove was discovered after Italian authorities asked the Swiss to look for an Etruscan sarcophagus illegally excavated and thought to have been smuggled out of the country into Switzerland. The request, made in March of 2014, launched a search of the warehouse. The sarcophagus they were looking for wasn’t there, but a lot more was.

This particular smuggler’s cove was discovered after Italian authorities asked the Swiss to look for an Etruscan sarcophagus illegally excavated and thought to have been smuggled out of the country into Switzerland. The request, made in March of 2014, launched a search of the warehouse. The sarcophagus they were looking for wasn’t there, but a lot more was.

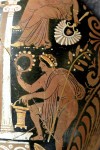

A search led by prosecutor Claudio Mascotto, from the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Geneva, at the Geneva Free Ports revealed an unexpected treasure. Two rare sarcophaguses of Etruscan origin – their lid representing a man and a woman lying – were found in a warehouse, as well as many other invaluable archaeological remains. The antiques had been stored there for more than 15 years, registered under the name of an offshore company.

The prosecutor ordered the seizure of the sarcophaguses first, then extended the decision to all items, considering their suspected illegal provenance. Among these are bas-reliefs, vases and fragments of decorated vases, frescos, heads, busts, and several other votive or religious pieces.

An expert examined the artifacts and determined they were likely looted from the central Italian regions of Umbria and Lazio which were Etruscan territory in the first millennium B.C. Investigators from the Carabinieri Art Squad were able to establish a connection between some of the artifacts and the tomb robbers whose shenanigans had sparked the initial investigation.

An expert examined the artifacts and determined they were likely looted from the central Italian regions of Umbria and Lazio which were Etruscan territory in the first millennium B.C. Investigators from the Carabinieri Art Squad were able to establish a connection between some of the artifacts and the tomb robbers whose shenanigans had sparked the initial investigation.

The legal machinery of Italy and Switzerland agreed that the objects should be returned to Italy, but the repatriation process was delayed by an appeal from the warehouse owner who wanted to keep the goods until he got paid for 15 years worth of storage. Why he had been so saintly as to allow a decade and a half of unpaid bills is unclear.

The press release from the Geneva Prosecutor’s Office didn’t name the person who filled the warehouse with ancient treasure, referring to him only as a “former high-profile British art dealer, whose name has been linked in the past to the trading of several looted antiquities throughout the world.” That’s Robin Symes. Here’s a quick summary of the Symes saga I wrote ages ago, but to make a brief overview of a long story even shorter, for many decades Symes was the antiquities dealer to the rich and famous and the biggest museums in the world. The champagne lifestyle of chauffeured Bentley and homes in London, New York, Athens and the Cyclades islands came to an abrupt end when his business parter and long-time companion, Christo Michaelides, died in an accidental fall in 1999. The subsequent lawsuit from the deep-pocketed Michaelides family drove Symes into bankruptcy and, thanks to his inability to stop perjuring himself for one second, jail.

The press release from the Geneva Prosecutor’s Office didn’t name the person who filled the warehouse with ancient treasure, referring to him only as a “former high-profile British art dealer, whose name has been linked in the past to the trading of several looted antiquities throughout the world.” That’s Robin Symes. Here’s a quick summary of the Symes saga I wrote ages ago, but to make a brief overview of a long story even shorter, for many decades Symes was the antiquities dealer to the rich and famous and the biggest museums in the world. The champagne lifestyle of chauffeured Bentley and homes in London, New York, Athens and the Cyclades islands came to an abrupt end when his business parter and long-time companion, Christo Michaelides, died in an accidental fall in 1999. The subsequent lawsuit from the deep-pocketed Michaelides family drove Symes into bankruptcy and, thanks to his inability to stop perjuring himself for one second, jail.

While the lawsuit was ongoing, Symes lived in Geneva where he could stuff untold ancient artifacts into Free Port warehouses. Some of the key lies he told on the stand, in fact, were about his warehouse activities. He told the court that he had five warehouses in Geneva holding his inventory when in reality he had 29 of them spread throughout London, New York and Geneva.

Symes, whose current whereabouts are unknown, cannot be prosecuted in Italy because the statute of limitations has expired, but this repatriation could have a chain reaction that puts pressure on the UK to return more than 700 disputed artifacts being held by the Symes’ liquidator. Objects in dispute have turned up on auction catalogues and in 2010 the Home Office instructed the liquidator to sell 1,000 pieces from Symes’ estate to settle his exorbitant tax bill. Italy complained vociferously and the sales were withdrawn, but the question of what to do with Symes’ stolen lucre is still unsettled. If Switzerland, which only ratified the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property in 2003 and was the pivot point for this illegal traffic for decades, can send Symes’ loot back to Italy, the UK should certainly feel the heat.

Symes, whose current whereabouts are unknown, cannot be prosecuted in Italy because the statute of limitations has expired, but this repatriation could have a chain reaction that puts pressure on the UK to return more than 700 disputed artifacts being held by the Symes’ liquidator. Objects in dispute have turned up on auction catalogues and in 2010 the Home Office instructed the liquidator to sell 1,000 pieces from Symes’ estate to settle his exorbitant tax bill. Italy complained vociferously and the sales were withdrawn, but the question of what to do with Symes’ stolen lucre is still unsettled. If Switzerland, which only ratified the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property in 2003 and was the pivot point for this illegal traffic for decades, can send Symes’ loot back to Italy, the UK should certainly feel the heat.