On November 14th, 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt was hunting bear in Mississippi with a party including Mississippi Governor Andrew Longino, several reporters and guide Holt Collier. Collier, born a slave in 1848, was a bear hunter of almost legendary status. He’d hunted bear from Texas to Alaska, killing thousands of them. He claimed to have stopped counting when he killed his 2,212th bear. In the Mississippi Delta, nobody was more qualified than Holt Collier to give the big-game hunting President the bear hunt of his dreams. When he was interviewed by the Federal Writers Project in the 1930s, Collier relayed how “It was going to be a ten day hunt, but the President was impatient. ‘I must see a live bear the first day,’ he said. I told him he would if I had to tie one and bring it to him.”

On November 14th, 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt was hunting bear in Mississippi with a party including Mississippi Governor Andrew Longino, several reporters and guide Holt Collier. Collier, born a slave in 1848, was a bear hunter of almost legendary status. He’d hunted bear from Texas to Alaska, killing thousands of them. He claimed to have stopped counting when he killed his 2,212th bear. In the Mississippi Delta, nobody was more qualified than Holt Collier to give the big-game hunting President the bear hunt of his dreams. When he was interviewed by the Federal Writers Project in the 1930s, Collier relayed how “It was going to be a ten day hunt, but the President was impatient. ‘I must see a live bear the first day,’ he said. I told him he would if I had to tie one and bring it to him.”

And that’s pretty much how it went. Collier and his specially trained pack of dogs cornered an old, grey-muzzled 235-pound black bear in a pond. The bear took out several of Collier’s dogs before the huntsman struck him on the skull with the butt of his rifle and managed to rope the wounded animal and tie him to a tree. When the rest of the party caught up, Roosevelt refused to shoot the injured, tied up bear. He thought it was “too easy.” John M. Parker, future governor of Louisiana and a friend of Theodore Roosevelt’s, had no such scruples. Guided by Collier, he stabbed the bear in the heart.

And that’s pretty much how it went. Collier and his specially trained pack of dogs cornered an old, grey-muzzled 235-pound black bear in a pond. The bear took out several of Collier’s dogs before the huntsman struck him on the skull with the butt of his rifle and managed to rope the wounded animal and tie him to a tree. When the rest of the party caught up, Roosevelt refused to shoot the injured, tied up bear. He thought it was “too easy.” John M. Parker, future governor of Louisiana and a friend of Theodore Roosevelt’s, had no such scruples. Guided by Collier, he stabbed the bear in the heart.

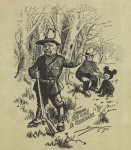

The reporters in the party recounted the President’s refusal to shoot the tied bear to their papers and the story made national news. On November 16th, 1902, a cartoon by Clifford Berryman ran on the front page of the Washington Post. In it, TR, dressed in his full Rough Rider uniform, stands with his back to a (white) guide holding a sweet, scared-looking bear cub by a rope tied around his neck. The President’s hand is raised, rejecting the offering of the tied bear. The caption says “Drawing the line in Mississippi.”

The reporters in the party recounted the President’s refusal to shoot the tied bear to their papers and the story made national news. On November 16th, 1902, a cartoon by Clifford Berryman ran on the front page of the Washington Post. In it, TR, dressed in his full Rough Rider uniform, stands with his back to a (white) guide holding a sweet, scared-looking bear cub by a rope tied around his neck. The President’s hand is raised, rejecting the offering of the tied bear. The caption says “Drawing the line in Mississippi.”

TR had little idea of the impact the bear story and Berryman’s cartoon would have. At a train stop in Newton, North Carolina, on his way back to Washington, D.C., a week after the event, Teddy spoke to the small crowd that had assembled clamouring to hear from him. Someone in the audience asked him “How about the bear?” and Roosevelt replied, laughing, “There was nothing about the bear.”

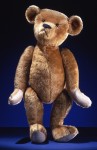

Businesses, on the other hand, quickly recognized the bear sensation could be of value to them. As early as November 23rd an umbrella company used the President and a bear to advertise its wares, but the real money idea came to a candy shop owner in Bedford–Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. Morris Michtom, a Jewish immigrant who had fled the pogroms of his native Russia while still a teenager in 1887, and his wife Rose read the stories of Roosevelt’s sportsmanlike refusal to shoot. They had a penny candy shop that also sold other small items like toys that Rose would make in the evenings. Inspired by Berryman’s cartoon of the sweet little bear, Rose cut some brown plush velvet into the shape of a bear cub, sewed it, stuffed it and put it in the shop window the next day. Morris named it “Teddy’s Bear.” By the end of the day, a dozen customers had asked to buy it.

Businesses, on the other hand, quickly recognized the bear sensation could be of value to them. As early as November 23rd an umbrella company used the President and a bear to advertise its wares, but the real money idea came to a candy shop owner in Bedford–Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. Morris Michtom, a Jewish immigrant who had fled the pogroms of his native Russia while still a teenager in 1887, and his wife Rose read the stories of Roosevelt’s sportsmanlike refusal to shoot. They had a penny candy shop that also sold other small items like toys that Rose would make in the evenings. Inspired by Berryman’s cartoon of the sweet little bear, Rose cut some brown plush velvet into the shape of a bear cub, sewed it, stuffed it and put it in the shop window the next day. Morris named it “Teddy’s Bear.” By the end of the day, a dozen customers had asked to buy it.

Morris realized they could have a successful sideline in stuffed bear sales, but he was concerned that he might get in trouble for using the President’s name without permission, so he wrote Roosevelt asking for his blessing. A little while later he received a reply from Teddy Roosevelt telling him to have at it, although he doubted his name would increase sales. TR’s modesty was misplaced. On February 15th, 1903, the first Teddy’s Bears went on sale at the Michtoms’ shop and they flew off the shelves, so much so that soon Morris Michtom dumped the penny candy business altogether and started the Ideal Novelty and Toy Company to mass-produce teddy bears.

Morris realized they could have a successful sideline in stuffed bear sales, but he was concerned that he might get in trouble for using the President’s name without permission, so he wrote Roosevelt asking for his blessing. A little while later he received a reply from Teddy Roosevelt telling him to have at it, although he doubted his name would increase sales. TR’s modesty was misplaced. On February 15th, 1903, the first Teddy’s Bears went on sale at the Michtoms’ shop and they flew off the shelves, so much so that soon Morris Michtom dumped the penny candy business altogether and started the Ideal Novelty and Toy Company to mass-produce teddy bears.

Teddy bears were instantly popular and almost instantly copied by other toy manufacturers. By 1906 the craze had swept the country, ushering in a new era of soft, cuddly plush toys replacing the dolls of yore. There was even a fashion among adult woman to drive teddy bears around in their cars and to carry around wherever they went.

Teddy bears were instantly popular and almost instantly copied by other toy manufacturers. By 1906 the craze had swept the country, ushering in a new era of soft, cuddly plush toys replacing the dolls of yore. There was even a fashion among adult woman to drive teddy bears around in their cars and to carry around wherever they went.

Of course there was some handwringing about the new fad. Rev. Father Michael G. Esper of St. Joseph, Michigan, denounced teddy bears from the pulpit as the instruments of “race suicide,” an obsession in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that “native” stock (ie, descendant of early European colonists, not actual Native Americans) were being outbred by more recent immigrants of the inferior “races” like the Irish and southern Italians. Esper fulminated:

“There is something natural in the care of a doll by a little girl. It is the first manifestation of the feeling of motherhood. In the development of those motherly instincts is the hope of all nations.

It is a monstrous crime to do anything that will tend to destroy these instincts. That is what the ‘Teddy bear’ is doing, and this is why it is going to be a factor in the race suicide problem if the custom is not suppressed. It is terrible enough that the present generation of parents in this country is leading us into grave danger by the practice of race suicide. If we cannot awaken the present generation let us at least save the future ones.”

Others rebutted that girls still treated their stuffed bears like babies, so the maternal instinct appeared intact. The September 12th, 1907, issue of The Nation gave the teddy bear even more credit: “The bear which waits around the corner to devour naughty little boys and girls loses its terrors when the child knows by experience what an amiable, comfortable beast it is. Thus the toy may have robbed childhood of one of its terrors.”

Others rebutted that girls still treated their stuffed bears like babies, so the maternal instinct appeared intact. The September 12th, 1907, issue of The Nation gave the teddy bear even more credit: “The bear which waits around the corner to devour naughty little boys and girls loses its terrors when the child knows by experience what an amiable, comfortable beast it is. Thus the toy may have robbed childhood of one of its terrors.”

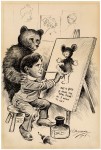

The fad was so inescapable that Theodore Roosevelt himself embraced the teddy bear as a personal emblem and of the Republican Party he led. Stuffed animal representatives became a recurring theme in political cartoons and campaigns. Toy companies, fearing that the teddy bear’s popularity would fade with its namesake out of office, rushed to figure out a new mascot associated with Roosevelt’s successor William Howard Taft. Taft’s gluttony provided just the opportunity. At a banquet in Atlanta, the new President requested “possum and taters” which he received in spades: an 18-pound opossum surrounded by sweet potatoes. And thus was born Billy Possum, the stuffed animal that was to displace the teddy bear. It lasted a year before manufacturers gave up. The teddy bear, meanwhile, remains a toy industry staple to this day.

The fad was so inescapable that Theodore Roosevelt himself embraced the teddy bear as a personal emblem and of the Republican Party he led. Stuffed animal representatives became a recurring theme in political cartoons and campaigns. Toy companies, fearing that the teddy bear’s popularity would fade with its namesake out of office, rushed to figure out a new mascot associated with Roosevelt’s successor William Howard Taft. Taft’s gluttony provided just the opportunity. At a banquet in Atlanta, the new President requested “possum and taters” which he received in spades: an 18-pound opossum surrounded by sweet potatoes. And thus was born Billy Possum, the stuffed animal that was to displace the teddy bear. It lasted a year before manufacturers gave up. The teddy bear, meanwhile, remains a toy industry staple to this day.