In 1962, construction workers in Groß Fredenwalde in Brandenburg, northeastern Germany, accidentally discovered human bones. An excavation unearthed the skeletal remains of six people dating to around 6,000 B.C. when the area was populated by the hunter-fisher-gatherers of the Mesolithic period. The site was re-excavated between 2012 and 2014, and archaeologists unearthed three more burials, these dating to between 6,400 and 4,900 B.C. All told, nine individuals were found in at least four graves, which makes this the oldest known cemetery in Germany and one of the oldest in Europe.

In 1962, construction workers in Groß Fredenwalde in Brandenburg, northeastern Germany, accidentally discovered human bones. An excavation unearthed the skeletal remains of six people dating to around 6,000 B.C. when the area was populated by the hunter-fisher-gatherers of the Mesolithic period. The site was re-excavated between 2012 and 2014, and archaeologists unearthed three more burials, these dating to between 6,400 and 4,900 B.C. All told, nine individuals were found in at least four graves, which makes this the oldest known cemetery in Germany and one of the oldest in Europe.

Mesolithic finds tend to be stone tools. Graves are rare and cemeteries are far rarer. This one is on the top of a hill. Archaeologists believe this was deliberate, that the Mesolithic people who buried their dead there over thousands of years chose the spot because it was so prominent in the landscape. In addition to whatever spiritual value the hilltop might have held, from a purely practical perspective it is easy to find, an important feature for a cemetery in use for 1,500 years. Also the area is replete with lakes, which made it resource-rich for a forager cultures.

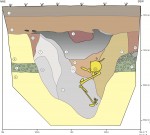

One of the burials discovered during the recent excavation is exceptional: it’s a young man who was buried standing upright about 7,000 years ago. The burial process was done in several phases. First the young man was placed into a vertical pit five feet deep, his back leaning against the wall of the pit. The pit was then filled with sand to a point above his knees which ensured the body would

One of the burials discovered during the recent excavation is exceptional: it’s a young man who was buried standing upright about 7,000 years ago. The burial process was done in several phases. First the young man was placed into a vertical pit five feet deep, his back leaning against the wall of the pit. The pit was then filled with sand to a point above his knees which ensured the body would  remain standing. The grave was then either left open or only cursorily covered. Scavengers helped themselves, leaving bite marks on some of the arm bones. Once the body was thoroughly decayed and the upper body had fallen apart into the pit, the grave was filled all the way to the top. A fire was then lit on top of the tomb.

remain standing. The grave was then either left open or only cursorily covered. Scavengers helped themselves, leaving bite marks on some of the arm bones. Once the body was thoroughly decayed and the upper body had fallen apart into the pit, the grave was filled all the way to the top. A fire was then lit on top of the tomb.

This is an unprecedented find in Central Europe, although there may be comparable burials in the Olenij Ostrov cemetery in Karelia, northwest Russia.

“The burial is unique in central Europe and therefore it is difficult to find a specific reasons for such treatment,” [excavation director at the Lower Saxony Department of Historic Preservation Thomas] Terberger told Discovery News.

“The young man also received grave goods and this is indicating an unusual, but honorable treatment of the body,” he added. “On this background, I see no good argument to interpret the burial as a kind of punishment.”

Another exceptional grave found near the standing burial is an infant burial in which ocher powder was scattered for ritual purposes. The entire grave was excavated in a solid soil block and transported to the University of Applied Sciences Berlin. The remains are in excellent condition, a very rare circumstance with infant remains because there wee, soft bones disintegrate easily. This is easily the best-preserved infant burial every discovered in Germany.

Another exceptional grave found near the standing burial is an infant burial in which ocher powder was scattered for ritual purposes. The entire grave was excavated in a solid soil block and transported to the University of Applied Sciences Berlin. The remains are in excellent condition, a very rare circumstance with infant remains because there wee, soft bones disintegrate easily. This is easily the best-preserved infant burial every discovered in Germany.

All of the remains found in this cemetery are so well preserved that researchers are optimistic they will able to determine people’s diet using stable isotope analysis. They also hope to recover viable DNA that will allow them to map the genome of the last hunter-gatherers in Brandenburg during the transition to farming. (The first farmers reached Central Europe from Southeast Europe about 7,500 years ago, so these remains date to both before and after that pivotal point.)

All of the remains found in this cemetery are so well preserved that researchers are optimistic they will able to determine people’s diet using stable isotope analysis. They also hope to recover viable DNA that will allow them to map the genome of the last hunter-gatherers in Brandenburg during the transition to farming. (The first farmers reached Central Europe from Southeast Europe about 7,500 years ago, so these remains date to both before and after that pivotal point.)

The study of the vertical burial has been published in the current issue of the journal Quaternary.