The Codex Purpureus Rossanensis is a 6th century Greek manuscript written in uncial script (upper case script with rounded letters in use from the 4th-8th centuries) that contains the gospel of Matthew, most of the gospel of Mark (verses 14-20 of chapter 16 are missing) and the Epistula ad Carpianum (a letter from Eusebius

The Codex Purpureus Rossanensis is a 6th century Greek manuscript written in uncial script (upper case script with rounded letters in use from the 4th-8th centuries) that contains the gospel of Matthew, most of the gospel of Mark (verses 14-20 of chapter 16 are missing) and the Epistula ad Carpianum (a letter from Eusebius  of Caesarea, the “Father of Church History,” to Carpianus on the concordance of the four gospels). Because of the letter and an illumination of all four evangelists, scholars believe the 188-page codex was originally more than double the size and included all four gospels. It’s not certain where it was written. Comparisons with other manuscripts suggest Antioch is a possibility, as is Byzantium.

of Caesarea, the “Father of Church History,” to Carpianus on the concordance of the four gospels). Because of the letter and an illumination of all four evangelists, scholars believe the 188-page codex was originally more than double the size and included all four gospels. It’s not certain where it was written. Comparisons with other manuscripts suggest Antioch is a possibility, as is Byzantium.

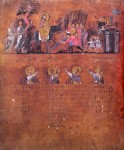

It is one of several surviving manuscripts of the New Testament known as the Purple Uncials or Purple Codices after their reddish or purple pages. The vellum was dyed the royal color and the text written in silver and gold ink. St. Jerome, author of the Vulgate, the first comprehensive translation of most of the Bible into Latin, defended himself against charges that he was rejecting the authority of the Greek writers of the Septuagint in his translation by dismissing the purple codices as pretty but inaccurate.

It is one of several surviving manuscripts of the New Testament known as the Purple Uncials or Purple Codices after their reddish or purple pages. The vellum was dyed the royal color and the text written in silver and gold ink. St. Jerome, author of the Vulgate, the first comprehensive translation of most of the Bible into Latin, defended himself against charges that he was rejecting the authority of the Greek writers of the Septuagint in his translation by dismissing the purple codices as pretty but inaccurate.

“Let whoever will to keep the old books, either written on purple skins with gold and silver, or in uncial letters, as they commonly say, loads of writing rather than books, while they leave to me and mine to have poor little leaves and not such beautiful books as correct ones.”

For them to have been held up as examples of old-fashioned scholarship, the purple Bibles must have been widespread in Christian theological circles when Jerome wrote that in 394 A.D.

For them to have been held up as examples of old-fashioned scholarship, the purple Bibles must have been widespread in Christian theological circles when Jerome wrote that in 394 A.D.

Most of the surviving Codices Purpurei date to the 6th century, but there are examples as early as the 4th or 5th century (Codex Vercellensis Evangeliorum,

Codex Veronensis, Codex Palatinus) and as late as the 9th century (Minuscule 565, Minuscule 1143). There are Purple Codices written in Greek and Latin, and one in Gothic (Codex Argenteus). They were created in numerous place within the Roman’s former sphere of influence, from Syria to Anglo-Saxon England to Byzantine Greece.

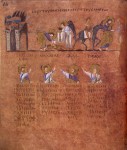

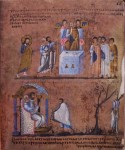

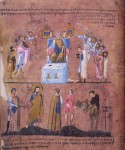

The Rossano Codex is particularly notable for its 14 illuminations depicting the life and ministry of Jesus. It’s one of the earliest surviving illuminated gospels and contains two of the first and most significant representations of Pontius Pilate. He’s depicted as a white-haired judge seated on a curule chair, a symbol of Roman political power because only magistrates were allowed to sit on them. Only one other purpureous codex from the 6th century, the Vienna Genesis, is illuminated, and it’s a fragment of the

The Rossano Codex is particularly notable for its 14 illuminations depicting the life and ministry of Jesus. It’s one of the earliest surviving illuminated gospels and contains two of the first and most significant representations of Pontius Pilate. He’s depicted as a white-haired judge seated on a curule chair, a symbol of Roman political power because only magistrates were allowed to sit on them. Only one other purpureous codex from the 6th century, the Vienna Genesis, is illuminated, and it’s a fragment of the  Septuagint, specifically the Book of Genesis, so no Jesus or Pilate. Images include the above-mentioned four evangelists, Lazarus being raised from the dead, the entry into Jerusalem, the parable of the ten virgins, the Last Supper (in which Jesus and Peter recline to dine) and washing of the feet, Jesus healing the blind man, the Good Samaritan, the suicide of Judas and the Pilate scenes.

Septuagint, specifically the Book of Genesis, so no Jesus or Pilate. Images include the above-mentioned four evangelists, Lazarus being raised from the dead, the entry into Jerusalem, the parable of the ten virgins, the Last Supper (in which Jesus and Peter recline to dine) and washing of the feet, Jesus healing the blind man, the Good Samaritan, the suicide of Judas and the Pilate scenes.

It was first brought to light by poet, literary critic and journalist Cesare Malpica in 1846, but the first to track it down to the sacristy of the cathedral of Rossano, Calabria, in southern Italy, and study it with scientific rigour were German theologians Adolf von Harnack and Oscar von Gebhardt published it internationally to great scholarly acclaim in 1879.

It was first brought to light by poet, literary critic and journalist Cesare Malpica in 1846, but the first to track it down to the sacristy of the cathedral of Rossano, Calabria, in southern Italy, and study it with scientific rigour were German theologians Adolf von Harnack and Oscar von Gebhardt published it internationally to great scholarly acclaim in 1879.

The manuscript has suffered many centuries of dismemberment, arduous travel, fire and a botched restoration in 1919 which applied hot jelly to the illuminated vellum leaves  causing them to turn transparent. Alarmed by its deteriorating condition, the Rossano archdiocese enlisted the aid of Rome’s Central Institute for Restoration and Conservation of Archival and Library Heritage (ICRCPAL). From 2012 until 2015, ICRCPAL conservators worked with chemists, physicists, biologists and the latest technology to analyze and repair the Codex. There’s a nice selection of photos of the Codex and its restoration on the project website. They’re small, sadly.

causing them to turn transparent. Alarmed by its deteriorating condition, the Rossano archdiocese enlisted the aid of Rome’s Central Institute for Restoration and Conservation of Archival and Library Heritage (ICRCPAL). From 2012 until 2015, ICRCPAL conservators worked with chemists, physicists, biologists and the latest technology to analyze and repair the Codex. There’s a nice selection of photos of the Codex and its restoration on the project website. They’re small, sadly.

In 2015 was added to UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register of documentary heritage. Now that the restoration is complete, the Codex will return to the Diocesan Museum where it is the featured exhibit. Three newly renovated galleries are dedicated to the manuscript: one to display the Codex itself, one in which a documentary film about the work is played, one dedicated to the restoration. A new climate-controlled, continuously monitored display case will house the fragile document. The Codex Purpureus Rossanensis goes back on display on July 2nd.

In 2015 was added to UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register of documentary heritage. Now that the restoration is complete, the Codex will return to the Diocesan Museum where it is the featured exhibit. Three newly renovated galleries are dedicated to the manuscript: one to display the Codex itself, one in which a documentary film about the work is played, one dedicated to the restoration. A new climate-controlled, continuously monitored display case will house the fragile document. The Codex Purpureus Rossanensis goes back on display on July 2nd.